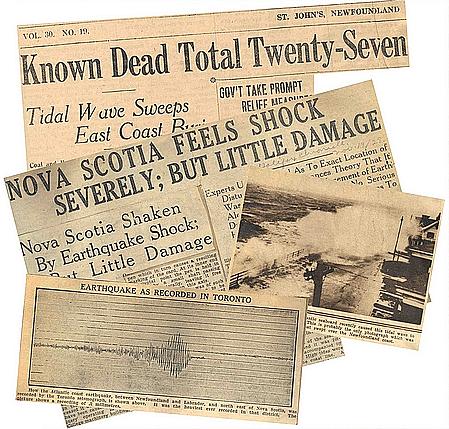

Tsunamis are such uncommon events on the East Coast that the term itself is rarely used. Yet on November 18, 1929, the unthinkable occurred. A largescale earthquake rocked the eastern coast of North America at 5:00 p.m. In St. John’s, Newfoundland, although no serious damage was sustained, the quake shook buildings, broke dishes, and upset furniture. Most people did not know what and earthquake was and thought it was an explosion.

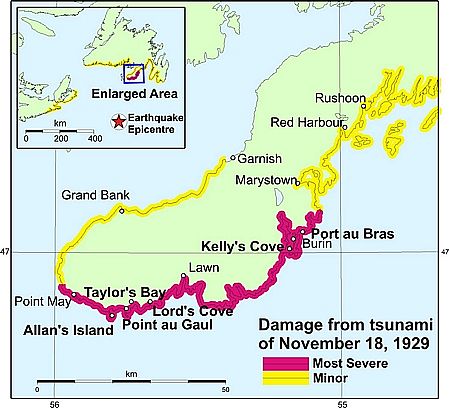

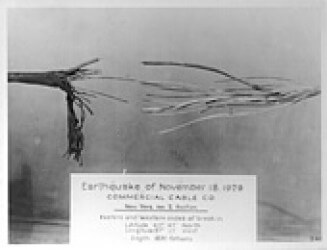

There ensued a debate about the location of the epicentre of the earthquake. Numerous broken underwater cables eventually led researchers to believe the epicentre was located 560 kilometres south of St. John’s, in the Atlantic Ocean.

At this time, the communication network in Newfoundland was sparse. Radio was in its infancy, there were few telephones, and because of the earthquake, many of the telegraph cables were down. Therefore, while the rest of the East Coast residents had settled back into their daily routines, they were unaware of the tragedy that had struck Newfoundland’s Burin Peninsula.

The fact that a tsunami had struck the area was not known by the outside world until three days after the quake when the steamship Portia arrived in Burin on a regularly scheduled call. A radio message from the ship alerted the world to what had happened.

The story emerged that the Peninsula had been struck by an enormous wave hours after the earthquake. The wave had drowned 27 people. Scores of homes, businesses, wharves, and fishing boats were smashed or swept away, along with the fish harvest, food, and fuel oil supplies.

As elsewhere along the coast, the earthquake was felt at 5:00 p.m. and damage was minimal. With nothing unusual occurring after the quake most residents returned to their activities.

Sometime after the quake, many people noticed the water draining out of the coves and harbours. In St. Lawrence, the harbour bottom, which on average is 10 metres deep, was visible in places. Not understanding what was happening, many residents moved to higher ground, probably saving many lives.

Two and onehalf hours after the earthquake, the wave arrived. It was unclear from witnesses whether there were two or three waves involved, but all agreed that the first wave was the most destructive. The wave height was reported to have been between 15 and 30 metres. The shape and width of the wave depended on the configuration of the coastline and the sea floor. The greatest impact of the wave was felt where the water was forced into a confined area, such as the coves and harbours.

The herculean wave either carried buildings inland and deposited them, or swept them into the harbours or out to sea when it receded. In St. Lawrence, 31 buildings were carried away. The wave entered and circled around the harbour, carrying buildings from one side to the other. Burin, a collection of a dozen or so communities, was also seriously affected, with many lives lost.

Several stories emerged about that night. Many people thought the towns were sinking as the water levels quickly rose.

While the wave smashed and destroyed many buildings, it simply lifted others off their foundations and floated them away. One store, 9 X 17 metres, was moved 60 metres inland and deposited in a meadow, with all its stock left intact.

People took to the remaining boats in search of people hanging to debris or trapped in floating homes. A kerosene lamp burning in the second floor window of one floating house led rescuers to a sleeping baby, whose family had been drowned on the first floor. A man, swept to sea, swam to another floating house only to find it was his own. The house was later towed back to shore and replaced on its foundation.

During the night a gale blew up, dropping temperatures and adding sleet and snow to the survivors’ misery.

The ferocity of the wave was not restricted to the land; it also tore up the seabed. This destruction of the seabed was believed by many to be the dominant factor in poor fish catches during much of the Great Depression.

Most of the energy of the wave was spent on the southern coast of the Burin Peninsula. The nearby communities of Fortune and Grand Bank, in the shelter of Fortune Bay, only experienced minor disruption. In Nova Scotia, the wave also struck Cape Breton, where one person was reported to have drowned.

With help from the files of Environment Canada.

rick

wow,how can one part of coast line be hit yet other parts not be,,,like halifax,,,and yarmouth,,,new york,,,,yet the eastern part of nova scotia was hit,,,i guess there is still a lot of guess still involved,,does eastern canada have sensors now for such just a thing now,,,in god we trust,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,,