The Treasure of Shellbird Island

Yes, b’y, there are few places in Canada richer in local folklore than the eastern shores of Newfoundland. The town of Torbay, for example, on the east coast of the Avalon Peninsula, is said to be haunted by a stygian hellhound with glowing red eyes- a Maritime counterpart to the legendary ‘black dog’ of the British Isles. Bell Island, in Conception Bay, is believed by some to be home to a phantom hag, a haunted mine, and a band of malevolent faeries. And St. John’s Harbour, according to the journal of 16th/17th Century English colonist Sir Richard Whitbourne, was once the domain of a mermaid. Such a rich folkloric tradition ought to be expected in the eastern half of this most storied of provinces, first to be discovered by Old World explorers and last to join the Canadian Confederation. After all, the history of eastern Newfoundland is as colourful as the motley facades that characterize St. John’s “Jellybean Row”.

The Rock’s west coast, on the other hand, is another story entirely. For centuries, Newfoundland’s western shores comprised a vast no-man’s land- a dark, desolate terra incognita devoid of any semblance of permanent settlement. Archaeological evidence (or lack thereof) indicates that the Dark Age Viking explorers who established a colony on the tip of the Great Northern Peninsula at the turn of the last millennia likely steered their longships clear of the Strait of Belle Isle- the gateway to the Gulf of St. Lawrence, which separates western Newfoundland from the Labrador Peninsula. 16th Century Basque whalers and cod fishermen who plied their trade in Red Bay, on the southeastern shores of Labrador, avoided lingering in the area anywhere north of Channel-Port aux Basques. Even the local Mi’kmaq and Beothuk First Nations appear to have largely shunned Newfoundland’s west coast prior to the advent of the fur trade. Although Breton explorer Jacques Cartier mapped the region in 1534, as did British Captain James Cook in 1767, the western shores of Newfoundland (sometimes called the ‘French Shore’ on account of France’s right to fish there from 1783-1904) remained sparsely populated until the mid-19th Century.

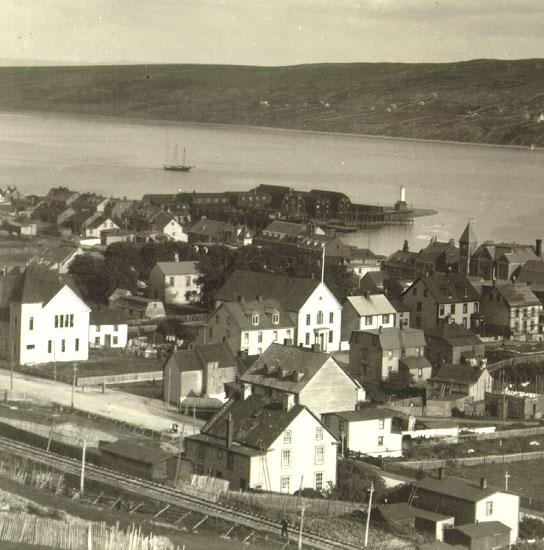

In spite of its shadowy past, the west coast of Newfoundland, with its tiny fishing communities, retains its own unique brand of folklore. Give a “bayman” a bottle of Screech and he might tell you the tale of the ghost ship of Bonne Bay- a phantom schooner which appears from time to time with shining lights and nary a soul aboard… before vanishing into thin air. Lark Harbour, tucked away in the Bay of Islands, is rumoured to be haunted by the spirits of a shipwrecked crew whose ghostly cries carry on the wind during storms. And then there is the tale of Shellbird Island and its mysterious treasure, the most famous regional folktale of all.

The Old Man in the Mountain

If you travel up the Bay of Islands from Lark Harbour, past the city of Corner Brook and up the Humber River, you’ll come to a small ait, or river island, known as Shellbird Island. This isle is overlooked by a 40-foot-tall cliff bearing a snarl of crags which bear close resemblance to the weathered countenance of an old bearded sailor- a natural landmark which locals fondly refer to as the Old Man in the Mountain.

Legend has it that the Old Man in the Mountain is privy to a centuries-old secret, namely the location of a treasure which lies buried on Shellbird Island. There are a number of different stories which purport to explain the origin of this mysterious treasure. One involves a Spanish galleon laden with Peruvian silver and Inca gold which foundered off the coast of Newfoundland during a storm. Another revolves around Eric Cobham and Maria Lindsey- a semi-mythical, 18th Century, Bonnie-and-Clyde-like Maritime pirate couple. But the most popular tale, first told many years ago by an ancient Nova Scotian sailor to a resident of the Bay of Islands, features a notorious “arch-pirate” of the Atlantic by the name of Peter Easton.

Captain Peter Easton

Although not nearly as well-known as many of his Caribbean contemporaries, Peter Easton, a Newfoundland-based buccaneer, was perhaps the most materially successful pirate to ever sail the high seas.

Little is known of Easton’s early life, although it is believed he was born around 1570 in England. He evidently established himself as a proficient mariner, as in 1602, Elizabeth I, Queen of England, commissioned him with protecting the English fishing fleet in Newfoundland. At that time, England and Spain were engaged in what is now known as the Anglo-Spanish War. Although the English Navy under the late Sir Francis Drake had effectively repelled the Spanish Armada at the Battle of Gravelines back in 1588, the Spanish Navy remained a formidable force, and the crews of Spanish galleons would do their best capture or sink any English vessels they encountered on the Atlantic.

For a year, Peter Easton performed his duty as a licenced privateer, capturing or sinking any Spanish or Basque vessels he believed posed a threat to Newfoundland’s English fishing fleet. In the spring of 1603, Queen Elizabeth I died and was succeeded by her first cousin once removed, King James I. The king immediately brokered a peace with Spain, ending the 19-year-long Anglo-Spanish War, and in doing so, revoked the licences of all English privateers. Rather than pursue a new legitimate career in England, Easton and his crew decided to continue doing that at which they excelled: looting Spanish vessels. And thus, Peter Easton became a pirate.

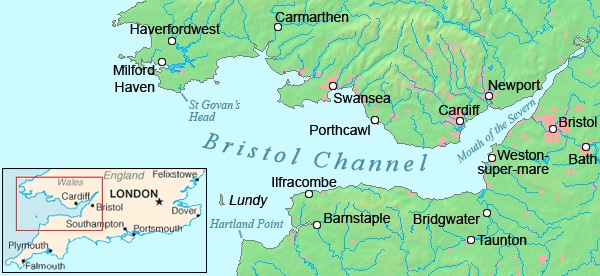

No longer beholden to English law, Easton proved to be a ruthless captain, routinely killing or jettisoning fellow shipmates with whom he took issue. Ruling over his crew with an iron fist, the ex-privateer led his pirates on raids all across the Atlantic and the Mediterranean, preying on Spanish treasure galleons, Barbary corsairs, and even English merchant vessels, terrorizing sailors from Morocco to the Caribbean. At one point, he even took his business to the Bristol Channel, the inlet which separates Wales from England’s South West Peninsula. Right under the nose of King James I, Peter Easton and his pirates extorted protection money from Welsh and English seamen before finally being driven back to Newfoundland by Sir Henry Mainwaring, a Captain of the Royal Navy who would later go on to become a fellow Newfoundland-based pirate himself.

In around 1611, Peter Easton and his crew established a fort at Harbour Grace, one of North America’s oldest towns, situated on Newfoundland’s Conception Bay on the Avalon Peninsula. In 1612, while Easton himself was in the Caribbean, a company of French Basques fishermen captured the fort. When Peter Easton and his crew returned from their voyage, the Basques sailed out to meet them. In the ensuing battle, which took place in the waters off Harbour Grace Island, Easton and his pirates defeated the Basque fleet, incurring forty seven casualties in the process. The bodies of Easton’s pirates were buried on Newfoundland near Harbour Grace, their cemetery comprising one of the only known pirate graveyards in North America.

Later that year, Peter Easton captured an English vessel off Ferryland, Newfoundland, another of his favourite haunts. The captain of this captured ship was none other than Sir Richard Whitbourne, the colonist who claimed to have encountered the aforementioned mermaid of St. John’s Harbour two years prior, and who also happened to be a representative of the English Crown. Easton tried in vain to convince Whitbourne to join him and his pirates, of which there were now about fifteen hundred. Instead, Whitbourne offered to seek clemency for Easton and his crew at the court of King James, and was allowed to do so after 11 weeks of imprisonment.

Following his release, Whitbourne returned to England, where he learned that the king had already issued a pardon to Easton and his men. Before he could convey this information to Easton, however, the so-called “arch-pirate” and five hundred of his buccaneers sailed to the Azores islands off the coast of Portugal, where they captured three Spanish galleons packed with Bolivian silver- a truly enormous prize.

Peter Easton retired from the pirate life in around 1614. He settled in the village of Villefranche-sur-Mer, on the French Riviera, where he married, acquired a palace, bought the title “Marquis of Savoy”, and lived like a king until his death in around 1620.

The Legend

According to legend, one variety of seagoing vessels that Peter Easton and his crew preyed upon while headquartered in Newfoundland were fur-bearing French merchant ships fresh from the ports of Quebec City and Montreal. During one such plundering operation, Easton and his men were spotted by a massive French man-of-war.

Painfully cognisant of the superior firepower of the French warship, Easton and his crew fled north to Newfoundland. They were pursued by the French marines. In an effort to evade the larger vessel, the pirates sailed up Newfoundland’s west coast, into the Bay of Islands, and further up the Humber River.

In the hold of Easton’s ship were three chests filled with gold- the spoils of a previous raid. Loathe to allow the gold to fall into the hands of the French, Easton ordered his first mate to bury it in a safe location nearby. Accompanied by another pirate, the first mate headed further up the Humber in a smaller boat with the three chests and a pair of shovels.

Several miles upriver, the first mate spotted the Old Man in the Mountain- the face of an aged sailor naturally graven into the cliff side. Hoping to use the landmark as a marker, the mate decided to bury the treasure on what is now known as Shellbird Island, the river isle upon which the Old Man gazed. With the help of his companion, he began digging three different pits on the island into which the treasure chests were to be interred.

In those days, the legend says, it was customary for pirates to bury a fresh corpse along with their loot so that the spirit of the dead man might guard the treasure until their return. In accordance with this custom, the first mate waited until all three holes were dug before drawing his flintlock and dispatching his hapless companion. The accomplished, the mate proceeded to bury the three chests, one of them with the dead man, and conceal the locations of the deposits before getting back into his boat and rowing downstream.

As fate would have it, the first mate never made it back to the ship. At a particularly turbulent section of the Humber known as Devil’s Dancing Pool, he capsized his rowboat and drowned, taking the secret of the treasure’s location with him to his watery grave.

Legend has it that Shellbird Island has yielded two of her three treasure chests. One was purportedly discovered by a group of treasure hunters in the late 1800s, her contents shared in secret. Another was dug up around 1934. As for the third chest, local lore maintains that it still lies somewhere beneath Shellbird Island, promising untold riches to any treasure hunter determined enough to find it and brave enough to defy the ghost of the pirate that guards it.

Sources

- Newfoundland Ghosts Linger; by John Lacy; in the Monday, September 1, 1975 issue of the Hartford Courant; courtesy of American Fortean researcher Mr. Gary S. Mangiacopra

- Ghost Stories of Newfoundland and Labrador (2010), by Edward Butts

- The West Coast of Newfoundland; by Bill Crant (April 29, 2000) and Terry Piercey (August 2002); provided by Newfoundland’s Grand Banks Site

- The Forgotten Bay: A Historical Survey of the Settlement of Lark Habour and York Harbour in the Outer Bay of Islands, Newfoundland (July 1997), by Stuart L. Harvey

- Pirate Gold! The Man in the Mountain & Corner Brook’s Treasure Island; by Dale Jarvis; in August 18, 2016 issue of NLUnexplained.ca

- No Colony for Old Men: Peter Easton in Conception Bay; in the June 1, 2017 issue of ConceptionBayMuseum.Wordpress.com

Want to Help?

If you enjoyed this article and would like to help support this website, please check out our online bookshop:

Ron

Name is listed on NL Government documents as being Shell Bird Island and not Shellbird Island.