The Wreck of the SS Ethie and the Hero Dog

Where does one begin to tell a story with more twists and turns than an Indy car race? Such is the story of the SS Ethie and the hero dogs. One blustery morning in 1919 a steam ship set sail from Cow Head on the western shore of Newfoundland. Later that same day, almost out of coal , coated heavily in ices and in peril of foundering, the captain of the stricken vessel aimed the ship towards land and crashed on a rocky beach. All 92 souls on board were taken off by rope chair, including a baby in a mail sack. The rope chair was attached to the rope fastened ashore by a man walking his dog on the lonely beach in bad weather. Victory in the midst of tragedy. A happy ending to a bad day. Certainly a story for the history books.

But the story did not finish with the rescue. In fact the story and controversy continues today.

Last year, on Mysteries of Canada, I wrote our first story of the SS Ethie. The story was based on what information Anna and I could find while visiting Gros Morne National Park. What a great story. Shipwrecks, heroes, babies. You couldn’t get better.

In March I received a telephone call from Dottie Olson who own the Roadhouse Lodge on Wrangell Island, Alaska. Dottie had an artifact that was associated with the SS Ethie. Dottie and Mysteries of Canada had been put together by none other than MoC contributor Robert Parsons.

I was hooked into the controversy of the SS Ethie and the Newfoundland Dog!

Here is the story!

The SS Ethie was a coal-burning steamer (also called a Stout Ship) that set sail from Cow Head, on the western shore of Newfoundland, heading south to Rocky Harbor. Captain Edward English was in command of a vessel that was on its last sail of the season carrying 92 passengers and crew. The date was December 10, 1919.

Captain English, aware that storm clouds were brewing over the area, chose to set sail to get the passengers home in time for Christmas. (Some people say that he was also put under a great deal of pressure from the shipping line to get underway!)

Within a few hours of departing, what started out as a small storm blew up into a fierce winter storm and ultimately into a blizzard. The vessel was constantly being blown towards the very rocky and dangerous shoreline. They burned most of their coal supply just trying to stay out a sea. As the coal supply diminished, Captain English realized his ship was lost. His thoughts then turned to saving the lives of the passengers and crew.

Consulting his charts, he made the decision to “beach” the SS Ethie at a place near Martin’s Point. This was not an easy decision for the coastline in this area was rife with dangerous reefs and high cliffs. But if you were going to go aground, Martin’s Point was the only place to do it.

As the SS Ethie approached the shore, a villager named Reuben Decker saw and understood the ship’s action. He rushed to the area of the impending “beaching” to help in the rescue.

When the SS Ethie finally came hard aground, the crew sent out a rope. It was picked up and secured to shore by Decker.

A breeches buoy was rigged up and used to carry the passengers and crew ashore. The youngest passenger, an eighteen-month old baby girl, was sent ashore in a mail sack.

All 92 passengers and crew of the SS Ethie were saved.

Sometime after the rescue most of the passengers and sailors returned home by train from Deer Lake. As they were want to do, the passengers and crew told stories of the spectacular rescue and there is no doubt that some facts were embellished. One “fact” entered into evidence on the train trip was that a dog was instrumental in the rescue effort by bringing the rope ashore from the ship.

A confusing part of the rescue story was a rumor that a Newfoundland dog was sent out from shore to fetch the rope that would help the people to shore. Another rumor was that a dog was lowered into the water from the vessel to swim the rope ashore. The latter idea is not as far fetched as one might think when one sees the wreckage of the ship, as it is today on the beach at Martin’s point. The ship’s hull would break the waves thus allowing the Newfoundland Dog, which would be a good swimmer and able to tolerate the cold water, to come ashore safely.

News of the rescue, the baby and the dog reached the offices of the Cornerbrook Western Star. The editor of the Star was also an Associated Press correspondent. He wired the story to the AP headquarters in the US where The Philadelphia Ledger picked it up. The Ledger’s editor took great interest in the story as he had visited the area the summer before.

Following the running of the story, a group in Philadelphia had a collar made complete with a silver medallion, Starry Cross, for presentation to the dog of Reuben Decker. The collar had a silver plate attached with the designation “HERO”.

The collar and medal were presented to Decker in 1920.

In 1923 the “sick soldiers of Camp Hill Hospital in Halifax awarded a silver cross to the hero-dog and that cross was also attached to the collar. What is the relationship of the hospital to the collar? We do not know at this time. Was an owner of the dog and collar a patient or on staff at Camp Hill Hospital?

In 2000, Dottie Olson has that collar, complete with silver plate and two medallions in Wrangell, Alaska.

How it got the other side of the continent is a mystery solved. We shall get to that later in this article.

The major controversy of the wreck of the SS Ethie story is whether in fact a dog was even involved with the rescue. And if a dog was involved, was it a Newfoundland dog or a crossbreed collie? Was the dog pictured at below Reuben Decker’s dog? This photograph was found in the same trunk (discussed later in this story) as the collar!

Twenty years after the rescue of the SS Ethie, Newfoundland writer Cassie Brown traveled to the western peninsula to interview persons from the shipwreck. She has written that, based on her interview with the First Officer of the SS Ethie, the story of the Newfoundland dog was an embellishment of the facts as told by one of the coalman after the rescue. This is story number one that is championed by Newfoundland author and publisher, Garry Cranford.

Story number two is that Reuben Decker’s dog, a cross-breed collie (see the photo at the right), named Wisher or Tang, was at the scene of the wreck and described as the dog from Newfoundland. Wisher, however, was not involved in the rescue, according to Garry Cranford.

Story number three comes from Newfoundland writer Michael McCarthy. Shortly after telling the story of the SS Ethie on radio, he received a phone call from what he remembered as the wife or daughter of the late Captain English. She said that not only was a Newfoundland dog involved in the rescue but also it was their (the English’s) dog who was lowered over the side to take ashore the rope.

What is the truth? I doubt we will ever know. But the story of the SS Ethie lives on in print, on the stage and in the hearts of many Newfoundlanders and dog-lovers all over the world.

But how did the collar get from Newfoundland to Dottie Olson’s Roadhouse in Alaska?

What we know is that Reuben Decker sold both the dog and the collar to William Orum of Saint John, New Brunswick for about $60.00. Orum’s intent was to put the dog on display to make few dollars. That was the last time the collar was seen in Newfoundland.

In fact that is the last record we have of the collar until it shows up in Alaska.

Dennis “Dinty” Kane arrived to Wrangell in 1923 with a large dog and a collar and metals designating the dog as a Hero. He lived in a rough hut with no heating or cooking facilities. According to Sue Bradley, a former resident of Wrangell, on really cold nights Kane and his big brownish-black dog (Sue called the dog “King”) would curl up next to the stove in the Bradley house to stay warm.

Sue used to enjoy riding on the back of the big dog and playing with the collar and metals.

Dennis Kane was a common laborer who probably came west from New Brunswick to find his fortune in the Cassiar Gold fields in western BC. Although we cannot say, he probably road the rails across Canada with thousands of other depression-era migrants who went in search of fortune in the gold fields of the west. My sources have told me that when he left New Brunswick Kane left behind a family including two sons. I wonder if the Kane boys (or their relatives) are alive today?

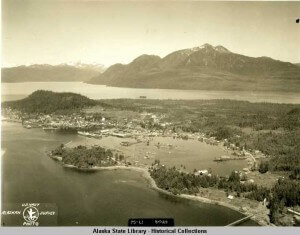

Wrangell, in south eastern Alaska, was a pivotal point in the trek to the interior of BC. Ships laden with supplies and prospectors steamed north from Vancouver and dumped their load near the mouth of the Stikine River at Wrangell. The Stikine River is the fastest flowing navigable river in North America. Its incredible speed is also its worst enemy. The Stikine is eroding year by year. The eroded silt of the river deposits at the mouth cause mud flats to build up. These mud flats make the river accessible only at high tide. Even at high tide parts of the flats are as little as 18 inches below the surface. Special ships and special captains were needed to get the barges up river to the gold fields.

Why Dennis Kane stayed in Wrangell instead of going inland could be as simple as running out of money. We shall never know because the major players in this part of the drama have all passed on. Sue Bradley is one of the few persons who have any recollection of Kane. However she was very young at that time.

Kane died under some suspicious circumstances in Wrangell in 1931. He is buried in the local cemetery after a funeral which was paid for by a group of local citizens. His grave stone, pictured at left, is very unique. It is a type of cement with little stones imbedded to spell out Kane’s name, date of birth and death. There are also a few symbols in evidence.

In his obituary (from the Wrangell Sentinel, dated July 10, 1931) Kane was reportedly from New Brunswick and was survived by two sons. The information about Kane was supplied by the US Marshall of the area, one C.W. “Shorty” Bradley, Sue Bradley’s father.

But what happened to the dog and the collar?

Sue Bradley doesn’t remember when the dog died but she remembers playing with the collar and the medals well into her teen years.

The collar stayed in the possession of Shorty Bradley, stored in a steamer truck, when he and his family left Wrangell for Talkeetna, about two hours from Anchorage. In 1966, Shorty died and the trunk was left with his wife Florence who moved back to Wrangell.

Florence died in 1985 after losing track of the trunk. Somehow the trunk ended up in the possession of a Jim Lovett (a dog sled owner and bushman). He kept it in an attic in an old house next to the present-day library in Wrangell.

In 1982, Charlotte Moody, when cleaning out an attic at the old house, spotted the trunk and took all the contents (including old newspaper clippings) to the dump except the collar and medals. Charlotte gave these to Dottie Olson because Dottie is a “collector extraordinaire” of old and useless things (no reflection on Dottie’s husband Dick intended). The collar sat above the bar at Dottie’s Roadhouse Lodge until it was returned to Newfoundland, temporarily, by the author.

The controversial story of the SS Ethie and the Dog Collar began on December 10, 1919 and it continues even today.

Sherry Welsh

We have the S.S. Ethie pictured as part of the coastal boats exhibit here at the Railway Coastal Museum. We also did a children’s puppet show “Dog in the Fog” about the tale. The collar and the mailbag would make for a great exhibit in the future if we were fortunate enough to have it donated.

Erik Miazga

As further to my last comment about the two paintings, they are both on display in a large seating area at Kingston General Hospital in Kingston, Ontario. The room is located on the fourth floor of the Connell wing. The spacious seating area is directly across from an elevator. The area is only a short walking distance from the end of the Kidd 4 Orthopedic post surgical unit.

Erik Miazga

I only learned of this tale by looking at a rough seawater painting donated to the Kingston General Hospital by a family named Irish. I believe the artist was by an Irish family member. There were two donated paintings, the other was a peaceful river scene signed by Irish. I could not detect a signature on the rough sea painting. But I do know that they were both donated by the same family. Only a small

card by the painting made mention of the SS Ethie.

trevor bennett

I grew up in the area and heard the stories. My father sailed on the SS Ethie but had transferred to a sister ship, by the ships owner’s;steers limited.of St Johns NL. ph 709 7833257