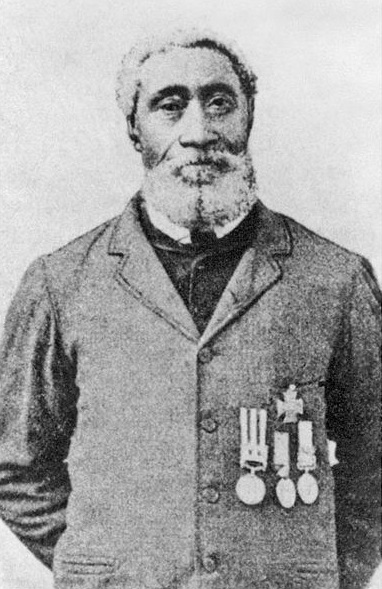

William Hall

And the Early Canadian Recipients of the Victoria Cross

From the martyrs of Queenston Heights to the veterans of Vimy Ridge, Canada has its fair share of war heroes who risked the ultimate sacrifice in service of Our Home and Native Land. Of the millions of Canadian soldiers who have fought for Queen and Country over the past two centuries, only 97 have received the Victoria Cross- the highest British military honour, awarded for gallantry in the face of the enemy. Some of the better-known Canadian recipients of this prestigious medal include Billy Bishop, the top British Empire fighter ace of WWI, and John Foote, the military chaplain who spent eight hours exposed to heavy fire while tending to wounded soldiers during the disastrous Dieppe Raid of 1942. Another celebrated recipient of the Victoria Cross, who happened to be the first black man to be awarded the honour, was a Nova Scotian sailor named William Hall.

A Nautical Vocation

William Neilson Hall was born in the town of Horton Bluff (now Wolfville, Nova Scotia) on a spring day in the late 1820s. Both of his parents were so-called “Black Refugees”- former slaves from Maryland, USA, who escaped north into British territory during the War of 1812. Like many Maritime boys who grew up during the Age of Sail, teenaged Hall found himself drawn to the sea. After spending several years working in a nearby shipyard, he joined the crew of a merchant vessel and began his career as a sailor.

The Mexican-American War

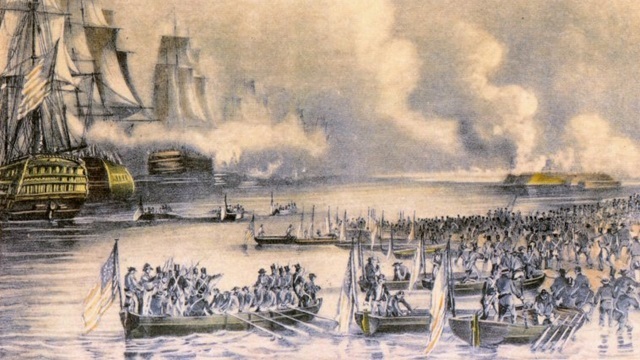

Within a few years, William Hall was serving in the United States Navy aboard a ship of the line called the USS Ohio. In March 1847, at the height of the Mexican-American War, Hall’s crew was dispatched to the city of Veracruz, Mexico, where it was to assist in the city’s capture.

Two days after the Ohio’s arrival, the Siege of Veracruz ended and the first large-scale amphibious assault conducted by U.S. military forces commenced. The American troops that disembarked at Veracruz would go on to capture Mexico City five months later.

The Crimean War

In February 1852, William Hall enlisted as an able seaman in the British Royal Navy and was assigned to a two-deck ship of the line called the HMS Rodney. Ever since the end of the Napoleonic Wars (1815), the British Royal Navy had enjoyed near-total command of the sea, ruling the waves from Cape Town to the Caribbean. The resultant Pax Britannica, or “British Peace”, coupled with the development of new ironclad steam-powered warships armed with exploding shell guns, had hugely reduced the incidence of ship-to-ship battles between Britain and her enemies; aside from a few dozen Chinese junks destroyed during the First Opium War, towns and fortresses were the primary recipients of mid-19th Century Royal Navy gunfire. As such, many British seamen, including William Hall, were trained in land-based warfare and required to undertake operations onshore.

Around that time, Tsar Nicholas I of Russia, who considered himself the protector of the Eastern Orthodox Church, demanded that the crumbling southerly Ottoman Empire grant him authority over all Orthodox Christians who resided in the Holy Land, Palestine being under Ottoman rule at that time. Emperor Napoleon III of France, a nephew of the great Corsican conqueror and the dictator of the newly-established Second French Empire, saw Nicholas’ demand as an attempt to exploit the ever-growing weaknesses of the Ottoman Empire and gain control of the important Byzantine waterways connecting the Black Sea with the Mediterranean- a move which could tip the European balance of power in Russia’s favour. Fearing the implications of Russia’s gaining access to the Mediterranean Sea, Napoleon demanded that the Ottoman Sultan instead grant France and the Roman Catholic Church authority over Palestinian Christians.

The Sultan denied Napoleon’s request and acceded to that of the Tsar’s, prompting Nicholas to move Russian troops into Ottoman territory on the pretext of carrying out his role as protector of the Christians living under Ottoman rule. This flagrant violation of Ottoman sovereignty was too much for the Sultan, who had no choice but to declare war on Russia. France and Britain, both of whom feared Russian expansionism, decided to back the Ottomans and declare war on the Russian Empire, and thus commenced the international conflict which would come to be known as the Crimean War.

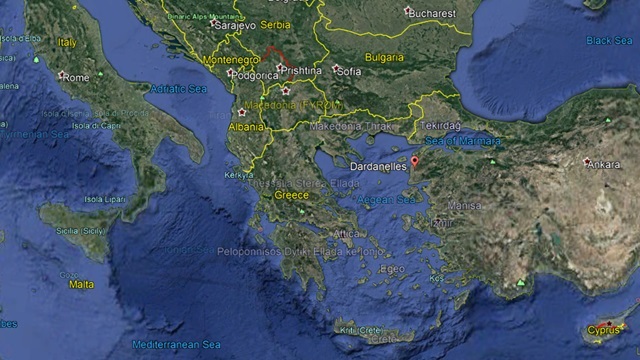

William Hall and the crew of the HMS Rodney were among the thousands of British and Commonwealth seamen who were subsequently dispatched to the Dardanelles, a narrow straight connecting the Aegean Sea with the Sea of Marmara; the gateway from Russia to the Mediterranean. Although the British and French were unable to assist their Ottoman allies for some time due to a lack of equipment, the Ottomans managed to drive the Russians from their territory.

Despite the withdrawal of Russian troops, France and Britain, who hoped to end the threat of Russian expansion into the Mediterranean for good, proposed to end the conflict on the condition that the Tsar relinquish his new role as protector of the Ottoman Christians and sign an agreement which would hinder southerly Russian expansion. Nicolas I refused, prompting Britain and France to plan an assault on Crimea- a large Russo-Ukrainian peninsula located at the northern end of the Black Sea.

In early September, 1854, British, French, and Ottoman troops sailed across the Black Sea and disembarked a short distance north of the Crimean city of Sevastopol, the main naval base of Russia’s Black Sea Fleet. Taken by surprise, an unprepared Russian force engaged the Allied armies on the heights above the Alma River but was forced to retreat. Instead of immediately pushing on to Sevastopol as they ought to have done, the Allied generals decided to besiege the Russian port city from the south. Accordingly, the French army marched around Sevastopol and established an operating base southwest of the city, while the British army established its own base to the southeast of Sevastopol, at a natural harbour called Balaklava. Shortly thereafter, the Russian army engaged the Allied forces about halfway between the British base and Sevastopol in the bloody Battle of Balaklava- a deadly encounter from which derived the phrase “the thin red line” (a reference to an unorthodox formation adopted by the 93rd Highland Brigade while repelling a Russian cavalry charge) and Alfred Tennyson’s famous poem “The Charge of the Light Brigade” (which glorified a suicidal British cavalry assault on a Russian artillery battery).

Early one foggy morning about two weeks after the Battle of Balaklava, the Russian army attacked an Allied camp not far from the town of Inkerman. Due to the misty conditions, the battle devolved into a series of isolated skirmishes and ferocious hand-to-hand frays which saw devastating losses on both sides. William Hall and the naval brigade of which he was a member fought in this Battle of Inkerman. Hall himself served as an artilleryman during the conflict and would later receive the Crimea Medal for his service.

William Hall and the rest of the Allied forces, most of them chronically malnourished and underequipped, spent two bitterly cold winters on the Crimean Peninsula battling cholera, frostbite, and misery in addition to Russian soldiers. Aided by a railway built from Balaklava to the frontlines by British civilian navvies and engineers, the Allied troops managed to maintain the Siege of Sevastopol and bombard the city with mortar and cannon fire on six separate occasions. Finally, after the British and French navies cut off Sevastopol’s supply lines and the Allied forces were supplemented by fresh reinforcements from the Kingdom of Sardinia, the besiegers launched several offenses against the city in the summer of 1855, one of which resulted in France’s capture of a strategically-important redoubt. The Russians abandoned Sevastopol to the Allies, and the Tsar capitulated shortly thereafter.

The Victoria Cross

In order to honour acts of valour performed throughout the Crimean War, Queen Victoria of Great Britain ordered the War Office to strike a new medal called the Victoria Cross, which was to be the most prestigious award that any British or Commonwealth military man could receive. According to legend, each Victoria Cross was cast from the iron of a Russian cannon captured at the decisive Siege of Sevastopol. One of the first soldiers to receive this new award was Alexander Roberts Dunn, a Canadian cavalryman who saved two fellow soldiers by killing four Russian horsemen with his sword during the Charge of the Light Brigade.

The Sepoy Mutiny

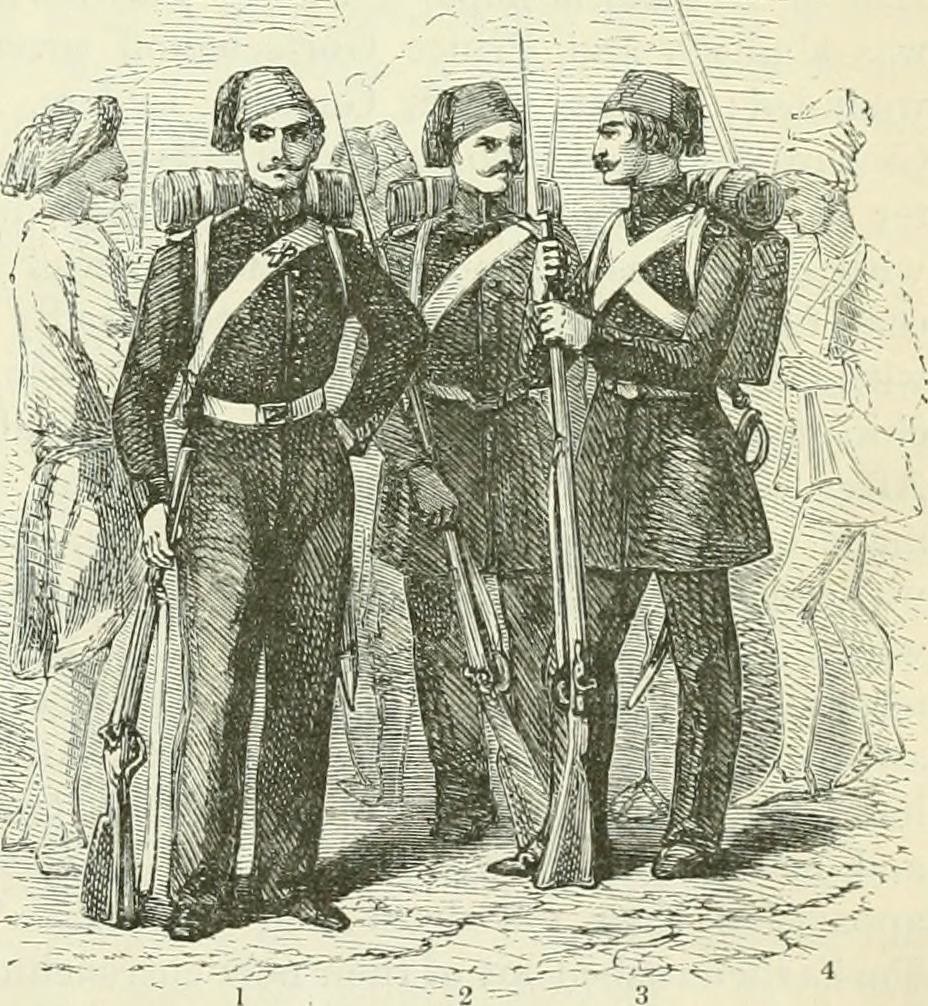

Although William Hall was not among the 111 riflemen, seamen, and hussars who received Queen Victoria’s new award in the wake of the Crimean War, he soon gained another opportunity to prove his mettle. On the other side of the world, in the regions of northern India governed by the British East India Company, a rebellion was brewing. Sepoys, or Indian soldiers who served in the army of the British East India Company, suspected that the British intended to destroy their traditional caste system and convert India’s Hindu and Muslim populace to Christianity. Many believed that the paper cartridges of the Enfield muskets they were issued, which soldiers were instructed to tear with their teeth when loading their guns, were greased with either beef tallow or pork lard- substances which Hindus and Muslims, respectively, were forbidden to consume.

In the spring of 1857, a Bengali sepoy named Mangal Pandey incited his fellow soldiers to revolt against their British officers. Pandey was arrested, court-martialled, and hanged following his unsuccessful attempt to kill several of his superiors. Throughout the following months, other sepoys across the Indian subcontinent similarly expressed their malcontent by burning barracks and refusing to participate in drills and parades. On May 10, 1857, a squadron of sepoy cavalrymen attempted to free members of another Indian cavalry regiment who had been arrested, court-martialled, and sentenced to long periods of imprisonment for disobeying the orders of their superior officers. The sepoys rescued their incarcerated comrades, killing all who resisted them, before storming the city of Delhi and slaughtering ever British subject they found therein. The revolt quickly spread throughout the city and much of Northern India, sparking what is known today as the Sepoy Mutiny, or the Indian Rebellion of 1857.

The sepoy mutineers nominated the reigning Mughal Emperor the figurehead of their movement and made Delhi their capital. No sooner had they established their new regime than they were forced to defend it from British and Gurkha troops dispatched from garrisons in the foothills of the Himalayas (Gurkhas being elite Nepalese soldiers famed for their uncanny fearlessness on the battlefield). The newly-arrived British-Gurkha force defeated the rebels at the Battle of Badli-ki-Serai and advanced on Delhi, laying siege to the city in early June. After three months of violent sorties and barrages, the counter-revolutionaries assailed and captured the city.

During the Siege of Delhi, a Canadian surgeon named Herbert Taylor Reade performed two feats of bravery which would later earn him the distinction of being the second Canadian to win the Victoria Cross. On September 14th, while tending to wounded British soldiers on one of the streets of Delhi, Reade was fired upon by a party of rebels who had climbed onto the roof of a nearby house. Instead of scrambling for cover, the surgeon drew his sword and charged at the sepoy rebels, effectively chasing them from the premises. Two days later, during an assault on a sepoy magazine, Reade was one of the first soldiers to charge through the breach and spike one of the rebel’s guns.

Back in June, while the British troops from the Himalayan foothills were entrenching themselves outside the walls of Delhi, another nearby British unit found itself on the defensive. In the southeasterly city of Lucknow, the tattered remnants of a British East Indian Company regiment were taking refuge in a building called the Residency, which had previously served as the residence of a local British official. These soldiers had just retreated from the Battle of Chinhat, fought several miles from the city, and were now surrounded by about 8,000 sepoy rebels eager to overwhelm their position.

Around that same time, William Hall was serving aboard the HMS Shannon, a frigate that had been tasked with delivering British troops to Hong Kong, where the Second Opium War was well underway. Upon making their delivery, Hall and his crewmates were ordered to sail for Calcutta, India, where they might assist the British in quelling the rebellion. Upon arriving in India, the Shannon was towed up the Ganges River to the city of Allahabad, its crew fighting every step of the way. Hall and his crewmates then disembarked and marched northwest to Lucknow with the task of relieving the defenders.

On their way to the Residency, the naval brigade met up with the army of Sir Colin Campbell, the newly-appointed Commander-in-Chief of British forces in India who was also preparing to relieve the garrison at Lucknow. On the morning of November 16th, 1857, the combined British force arrived at the city and made its way toward the Residency. Not far from their destination, the soldiers were surprised by a heavy barrage of musket fire administered by an army of sepoy rebels who had ensconced themselves within a thick-walled mosque. On Campbell’s orders, William Hall and members of the Shannon’s naval brigade quickly hauled their naval cannons into position 20 yards from the mosque’s wall and returned fire. Exposed as they were, the naval artillerymen made easy targets for the Indian marksmen and grenadiers. One by one, Hall’s fellow cannoneers were shot down or torn apart by shrapnel. Risking near-certain death, Hall and one of his shipmates, an English lieutenant named Thomas Young, dutifully held their post, loading and firing their 24-pounder howitzer into the mosque as musket balls whizzed above their heads. Soon, every one of their comrades lay either dead or wounded, yet Hall and Young kept on firing. Miraculously, Hall and the English lieutenant managed to breach the mosque’s southeastern wall, allowing Campbell’s men to storm the building and neutralize the enemy. Later that day, the British pushed on towards the Residency and successfully evacuated its hapless defenders.

After the Sepoy Mutiny was finally quelled, William Hall was recommended for the Victoria Cross by his captain, Sir William Peel- a fellow veteran of the Battle of Inkerman and the Siege of Sevastopol who had earned his own Victorian Cross during his service in the Crimean War. On October 28th, 1859, Hall was awarded this supreme British honour for his bravery at Lucknow by Rear Admiral Charles Talbot, the Commander-in-Chief of the British Royal Navy. He was the third Canadian to receive the Victoria Cross.

William Hall remained with the Royal Navy for the next seventeen years, serving aboard the HMS Donegal and the HMS Royal Adelaide and attaining the rank of Petty Officer First Class. He retired from the Navy in 1876 and returned to his hometown of Horton Bluff, where he lived with two of his sisters and his niece and eked out a modest living as a farmer.

William Neilson Hall died on August 27th, 1904, and was buried without military honours in the local churchyard. In 1945, his body was disinterred and reburied in the nearby town of Hantsport, Nova Scotia. A commemorative cairn was later erected overtop of his grave. Today, Hall’s Victoria Cross sits on display at the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic in Halifax, serving as a reminder of that great Canadian war hero who stood his ground and remained faithful to his duty while facing imminent death, risking life and limb in service of his country.

Lt Col Simon Dean OBE

Thanks you for this very well written account of William Halls bravery.

An incredible man whose sense of loyalty and duty was supreme.

My grandfather was also awarded the VC (Donald Dean) and I am always delighted to read these accounts, especially of our brother Candadian.