Back to The Nine Years’ War in Canada.

Back to 1689: The Acadian Theatre.

The Nine Years’ War in Canada- 1690: The Acadian Theatre

The Raid on Salmon Falls

Following Benjamin Church’s first Acadian raid, things were quiet in Acadia and New England for seven months. Then, in the spring of 1690, the governor of Canada ordered two military officers- Joseph-Francois Hertel and his son, Jean-Baptiste- with leading a raiding expedition against New Hampshire. On March 27, 1690, the two French officers, twenty six French Canadian soldiers, and a war party of Abenaki, Mi’kmaq, and Maliseet warriors surrounded the New English settlement of Salmon Falls (present-day Berwick, Maine). The warriors attacked the village and killed thirty four of its residents before burning the settlements’ buildings and their contents, including the livestock within them. The settlement’s remaining fifty-four inhabitants, most of them women and children, were captured and later carried off to Acadia.

The Battle of Falmouth (1690)

a.k.a. The Battle of Fort Loyal

After the raid on Salmon Falls, the Hertels and the Wabanaki war party waited for reinforcements, engaging briefly with a small militia from Portsmouth, New Hampshire, which had come to harry them. Within a month, they were joined by Jean-Vincent de Saint-Castin and several hundred Abenaki warriors. Their ranks swelled, the Acadians marched on the nearby village of Falmouth (also known as Casco)- the settlement which Benjamin Church and his Rangers had saved from Wabanaki warriors the previous autumn.

After the raid on Salmon Falls, the Hertels and the Wabanaki war party waited for reinforcements, engaging briefly with a small militia from Portsmouth, New Hampshire, which had come to harry them. Within a month, they were joined by Jean-Vincent de Saint-Castin and several hundred Abenaki warriors. Their ranks swelled, the Acadians marched on the nearby village of Falmouth (also known as Casco)- the settlement which Benjamin Church and his Rangers had saved from Wabanaki warriors the previous autumn.

On May 16, 1690, the five-hundred-man French-Indian war party arrived at Falmouth and attacked the settlement, at which stood a palisaded bastioned called Fort Loyal. The New English settlers, who were hugely outnumbered, managed to hold off the attackers for four days, all the while enduring a withering barrage from the attackers, who took up position in a deep gully which sheltered them from New English musket fire. Knowing that they would incur heavy losses if they assaulted the fort directly, the besiegers dug a zigzag-shaped trench towards the bastion until they were close enough to lob cast-iron hand grenades over the palisades.

On May 20, the defenders finally surrendered. Despite promises of save passage given by the Frenchmen, the Wabanakis proceeded to mercilessly massacre the settlement’s inhabitants. When the slaughter was complete, the victors piled the corpses of the slain in a large heap outside the village. The fort’s commander, Captain Sylvanus Davis- one of the few New Englanders who survived the massacre- was captured and eventually brought to Quebec.

The fall of Fort Loyal gave the Wabanakis free reign to pillage and plunder with impunity throughout the countryside. In the week that followed the Battle of Falmouth, the Acadian Indians slaughtered forty New English settlers in various small-scale massacres that took place throughout the Acadian-New Hampshire borderlands.

The Battle of Port Royal (1690)

While the Hertels, Saint-Castin, and their native allies had been busy exchanging fire with the residents of Falmouth, another battle was taking place in the heart of Acadia.

Up until this point, all the Acadian operations in the Nine Years’ War had been coordinated from Fort Meductic, on the shores of what is now New Brunswick. The capital of Acadia, however, was the village of Port Royal, the second oldest French settlement in the New World, situated on the southwestern shores of the Acadian Peninsula (i.e. Nova Scotia) on the Bay of Fundy.

The settlement of Port Royal was no stranger to conflict. Back in 1613, the village had been razed by a party of intrepid New English raiders. In 1627, it had been captured by Scottish noble Sir William Alexander, who converted it into the capital of the short-lived colony of Nova Scotia. Throughout the 1640s, Port Royal- in French hands once again- was the setting of two battles fought during the Acadian Civil War. And in 1654, three hundred English soldiers, under the orders of Oliver Cromwell (leader of the Commonwealth of England) took the village by force.

On May 19, 1690, Port Royal was attacked for a sixth time by 225 New English sailors and 446 provincial soldiers under the command of Sir William Phips.

William Phips was considered something of a homegrown hero in New England. A lowborn shipwright and lumber merchant from the colony of Massachussets, he had allowed his hard-won livelihood to literally go up in flames in order to save the lives of the residents of a particular village during a Wabanaki raid that took place during King Philip’s War. More recently, he had been awarded a knighthood from King William III for salvaging the contents of a sunken Spanish treasure galleon in the Caribbean, becoming the first native New Englander to earn the honorific ‘Sir’. Despite Phips’ complete lack of military experience, the Massachusetts militia promoted him to the rank of Major General in the spring of 1690 and gave him command of the naval expedition against New France.

Upon approaching the capital of Acadia, Phips found, to his delight, that Port Royal’s ninety soldiers were actually in the process of dismantling their fortifications so that stronger ones could be built in their place. None of the fort’s cannons were presently functional, and to top it off, the village’s armory held a total of nineteen muskets at that time. The garrison surrendered without a fight.

For some reason, on which French and English accounts of the incident disagree, Phips perceived that the Frenchmen were attempting to withhold some of their town’s spoils from him and flew into a rage. He claimed that the French had breached the terms of their surrender before seizing not only the contents of the fort, but also the private property of the village’s citizens.

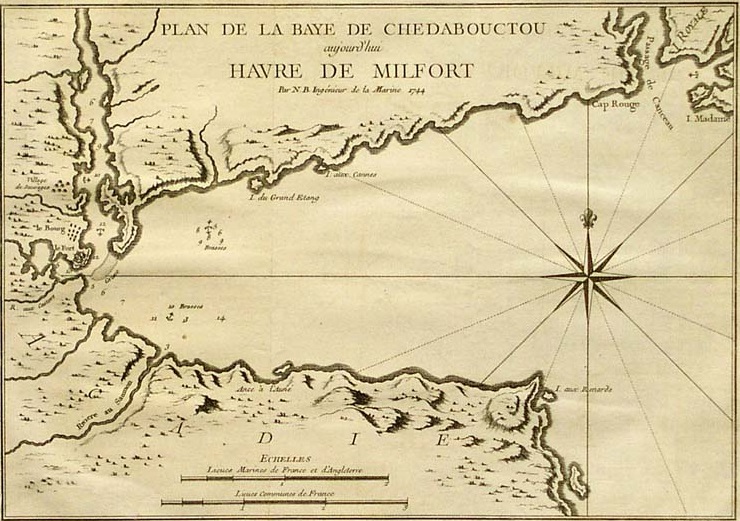

The Battle of Chedabucto

About a month after his capture of Port Royal, Sir William Phips tasked one of his officers, Captain Cyrian Southack, with raiding the Acadian village of Chedabucto, situated at the tip of the Acadian Peninsula just across the Chedabucto Bay from Ile Royale (i.e. Cape Breton Island). In addition to housing a French military post called Fort Saint Louis, Chedabucto served as the headquarters of the Company of Acadia, an important French fishing company.

On June 3, 1690, Captain Southack and eighty-eight New English soldiers stormed Fort Saint Louis. Although they were heavily outnumbered, the twelve Acadian soldiers who manned the fort put up a fierce six-hour defense. When the New Englanders began to firebomb the fort, the French defenders realized that future resistance would be futile. They surrendered to Southack, who allowed them to retreat across the Gulf of St. Lawrence to the colony of Plaisance, on the island of Newfoundland. Upon capturing the fort, Southack proceeded to destroy 50,000 crowns-worth of salted cod that had been garnered by the Company of Acadia, dealing a major blow to the New French fishing industry.

Church’s Second Expedition

In the fall of 1690, Benjamin Church prepared for his second expedition to Acadia. Several months earlier, he had been designated the sad task of burying the bones of the New English settlers who had been massacred at Falmouth- the same settlers whom he and his men had saved from Abenaki warriors one year earlier. Eager to avenge their deaths, Church and three hundred volunteers of both New English and aboriginal extraction set out for the ruins of Fort Pejepscot (present-day Brunswick, Maine), and English fort that had been abandoned in the wake of the Glorious Revolution.

Church and his men arrived at the desolate Fort Pejepscot on September 11, 1690. From there, they trekked forty miles up the Androscoggin River to an Abenaki village. The few warriors who resided in the village at that time became aware of Church’s presence and fled as his men approached the settlement. Some of the New English and indigenous marksmen fired at the braves as they rowed their canoe across the Androscoggin River and three of them received fatal shots in the back.

Upon taking the village, Church and his men found a number of women, children, and old Abenaki men huddled within the wigwams. Among the Indians were five filthy, half-starved New English prisoners. In a brutal act of psychological warfare, Church put a number of villagers to death, subjecting them to a cruel form of execution known in Italy as mazzatello- a method of capital punishment characterized by blunt trauma to the head which, in this case, was likely administered by war clubs or gun stocks. Two elderly women were spared the slaughter so that they might relate the incident to the Abenaki warriors when they returned, along with a message from Benjamin Church instructing them to bring all their English captives to Salmon Falls within two weeks if they ever hoped to see their wives and children again.

Church took the rest of the villagers captive and interrogated them, quickly learning that a major Acadian offensive was in the works. He proceeded to burn the settlement and its huge store of corn, leaving a small quantity of food for the two elderly women he chose to leave behind, and marched his prisoners down the river to vessels that awaited him there.

Church took the rest of the villagers captive and interrogated them, quickly learning that a major Acadian offensive was in the works. He proceeded to burn the settlement and its huge store of corn, leaving a small quantity of food for the two elderly women he chose to leave behind, and marched his prisoners down the river to vessels that awaited him there.

Church and his men spent the remainder of the day exploring the mouth of the nearby Saco River, where they rescued a New Englishman from his Abenaki captors. As the ships were crowded, three companies of the New English force decided to spend that night on shore at what is now Cape Elizabeth, Maine, known at that time as Purpooduc Point- a decision which would prove near-disastrous.

That night, one of the force’s Indian sentries heard a man cough in the bush, followed by the cracking of sticks. When he informed his companions that he suspected they were being watched, they laughed at him and said that the ‘cough’ he heard was probably the snort of a wild boar.

At dawn, the poor sentry was vindicated when a party of Abenaki braves rushed into the camp screaming war cries. Fortunately for the New Englanders, the morning mist had dampened the Abenaki’s gunpowder, delaying the timing of their first volley. The Englishmen retreated to the shore, where they were joined by the soldiers and warriors who had spent the night on the boats. Bolstered by these reinforcements, the New Englanders chased their assailants back into the woods. Church lost seven soldiers in this skirmish, and twenty four of his men were wounded. As was typical of the Nine Years’ War, the number of casualties the Abenaki sustained was a mystery since, according to the custom of the natives of the Atlantic Northeast, they had carried their dead and wounded with them into the forest.

Promises of a Prisoner Exchange

In October 1690, the Abenaki chiefs of the Androscoggin River appeared at the town of Wells (now Wells, Maine) under the white flag of truce and appealed to the town’s resident militia captain, asking that the New Englanders return the wives and daughters that Benjamin Church had taken during his second expedition to Acadia. The natives claimed that they wished to make peace with the English, and so a prisoner exchange was arranged for that November.

The scheduled meeting went as planned, although the Abenaki chiefs brought a only ten New English captives with them for exchange- a mere fraction of the prisoners they had taken during those first few years of the Nine Years’ War. After a six-day parley, the natives agreed to a truce which would last until the following spring. In May 1691, the two parties were to meet a second time, whereupon they would exchange all of their captives and agree to a permanent peace.

Leave a Reply