Back to The Nine Years’ War in Canada.

The Nine Years’ War in Canada- 1689: The Acadian Theatre

Background: King Philip’s War

By the time the Nine Years’ War broke out, British and French colonists on the Atlantic Coast were spoiling for a fight. Over a decade earlier, a handful of Algonquin tribes had warred against the settlers of New England in a devastating three-year conflict called King Philip’s War (‘King Philip’ being the nickname of Chief Metacomet, a powerful leader of the Wompanoag Indians). The French Acadians took advantage of the conflict by incentivizing the Wabanaki Confederacy, an alliance of five Acadian First Nations with whom they were friendly, to attack the Englishmen. From 1675 to 1677, the Wabanaki tribes engaged in annual raiding campaigns against New English settlements, prompting a prominent New English leader named Richard Waldron to eventually retaliate with a strike on an Acadian Mi’kmaq settlement.

By the time King Philip’s War ended in 1678, the English and French colonists on North America’s Atlantic coast had grown to resent each other and their respective First Nations allies. One incident which starkly illustrates this sentiment took place in the summer of 1677, when a party of settlers from the village of Marblehead, Massachusetts, hazarded a fishing trip off the southern coast of the Acadian Peninsula (i.e. present-day Nova Scotia). Not far from shore, the fishermen were captured by a party of Mi’kmaq warriors who hijacked their boats and commanded them to sail for a certain Indian village off the coast of what is now Maine. When they learned that they were to be executed, the New Englanders overpowered their captors, throwing most of the Mi’kmaq into the sea and keeping two of them as prisoners-of-war before rowing for home. When they finally slipped into Marblehead with their captives, the fishermen were mobbed by a throng of New English ladies who had lost fathers, husbands, and sons in the war against the natives. Armed with sticks and stones, the furious women set upon the Indian prisoners, attacking any of the fishermen who tried to protect them. Left with little choice, the New Englishmen eventually relinquished their captives and watched in helpless horror as the women vented their rage upon them. According to one colonist who witnessed the atrocity, “we were kept at such distance that we could not see [the prisoners] till they were dead, and then we found them with their heads off and gone, and their flesh in a manner pulled from their bones.”

The Northeast Coast Campaign

When King Philip’s War finally ended in 1678, the Atlantic Northeast enjoyed ten years of relative peace, although the New Englanders and the Wabanaki tribesmen neither forgot nor forgave the atrocities they had suffered at each other’s hands. The Abenaki Nation- one of the five tribes of the Wabanaki Confederacy- finally broke the spell in early 1688, launching a series of surprise raids against New England. That spring, Edmund Andros, the widely unpopular governor of what was then the Dominion of New England, retaliated by launching a minor raid against Acadia, plundering an Abenaki village situated on the shores of what is now southern Maine. Significantly, this village was home to by Jean-Vincent de Saint-Castin, an eccentric French officer who lived as a chief among the Abenaki Indians, and who had almost singlehandedly convinced the Wabanaki Confederacy to go on the warpath against New England during King Philip’s War. Although he plundered the rest of the village, Andros was careful not to desecrate the small altar and religious artifacts that the Catholic officer kept in his home- an act for which he was criticized by his zealous Puritan countrymen.

Four months later, the New Englanders carried out a second raid against the fishing village of Chedabucto (now Guysborough, Nova Scotia), situated on the northeastern shores of the Acadian Peninsula. The Wabanaki Confederacy countered by raiding the New English villages of New Dartmouth (now Newcastle), Yarmouth, and Kennebunk. By the time the Nine Years’ War was declared in Europe, the conflict in the North Atlantic was already in full-swing.

The Raid on Dover

On June 27, 1689, an incident took place in the village of Dover, one of the oldest settlements in New Hampshire, which was more a legacy of King Philip’s War than a development of the Nine Years’ War.

Back in 1676, a band of Indian refugees had taken up residence in the forest surrounding Dover. The town’s leader, Richard Waldron, a Major in the Massachusetts militia, was ordered to attack these natives and turn any captives he managed to take over to them. Waldron, however, had recently made a peace pact with these Indians and had no desire to do battle with them. Instead, he fulfilled his orders through duplicity, disarming the natives by inviting them to discharge their firearms in a mock battle. The natives were subsequently captured and brought to Boston, where many of them were executed or sold into slavery in the Caribbean.

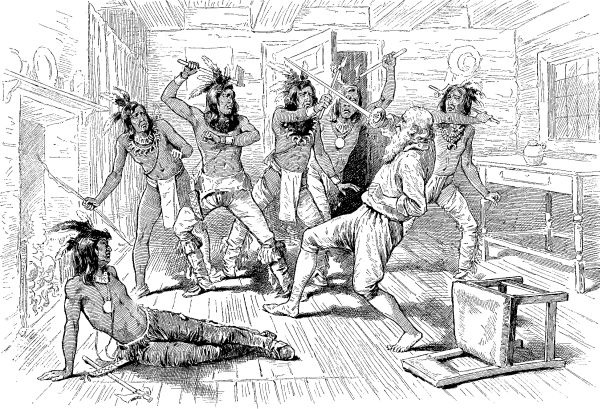

The natives of New Hampshire had not forgotten Waldron’s treachery, and thirteen years after the incident, they decided to take revenge. On the eve of June 27, 1689, a number of Indian women appeared at each of the houses in Dover and asked if they could spend the night. The residents of all but one home invited the women inside. That night, the native women quietly unlocked the doors of the houses they occupied, allowing Indian warriors to sneak inside, tomahawks and scalping knives in hand, and slaughter or capture the residents therein. The white-bearded Major Richard Waldron, now 74 years old, attempted to fight off the braves who entered his own home with his sword. He was eventually overpowered by his attackers and tied to a chair, whereupon the natives tortured him to death, severing his fingers, cutting off his nose and ears and stuffing them in his mouth, slicing him across the chest and belly as if to “cross out” their trading account with him, and finally forcing him to fall on his own sword.

The Siege of Pemaquid (1689)

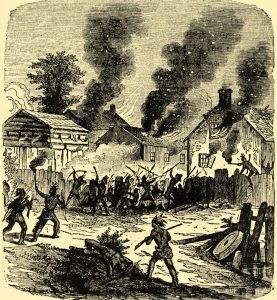

A few months later, Jean-Vincent de Saint-Castin, the French officer-turned-Abenaki chief who had played a pivotal role in King Philip’s War, decided to personally lead his own offensive against New England. On August 2, 1689, Saint-Castin, a French missionary named Father Louis-Pierre Thury, an old Abenaki chief named Moxus, and a war party consisting of about 200 Abenaki braves surrounded Fort Charles, a palisaded English trading post located in the village of Pemaquid (now Bristol, Maine), killing or capturing any settlers they came across in the countryside. The few dozen defenders garrisoned in the fort exchanged shorts with the attackers throughout the day, and by sunset, most of them were wounded.

The following morning, the defenders surrendered, and the Abenaki allowed them to retreat to Boston. Many of the villagers, however, were kept as prisoners and eventually taken to Fort Meductic, a fortified Maliseet village located just outside present-day Meductic, New Brunswick. One of these captives was nine-year-old John Gyles, who would one day write of his experiences on the Northeastern frontier in his 1736 autobiography Memoirs of Odd Adventures, Strange Deliverances, Etc. in the Captivity of John Gyles.

As the defeated New English defenders limped away from Pemaquid, the Abenaki put the fort and the surrounding settlement to the torch.

The Battle of Deering Oaks

In response to the raid on Pemaquid, the government of Massachusetts tasked one Major Jeremiah Swaine with leading a 600-man militia to secure the Acadian-New Hampshire border. While Swaine and his men were patrolling the region, a party of Abenaki warriors audaciously attacked the village of Oyster River (present-day Durham, New Hampshire) right under their noses, killing twenty one settlers, including three or four children, and taking a number of prisoners. The natives retreated north without suffering any reprisals from Swaine, who had dispatched an unsuccessful scouting party to hunt them down.

Disappointed with Swaine’s performance, the government of Massachusetts recalled the Major and tasked a seasoned military commander named Benjamin Church with carrying out raids on Acadia.

A veteran of King Philip’s War, Benjamin Church had long since realized that the military tactics commonly employed in Europe- characterized by disciplined formations, ostentatious uniforms, and pitched battles- were ineffective on the North American frontier. Accordingly, he studied and trained his own soldiers in the guerrilla tactics of the natives, forming his own unit of special light infantrymen who constituted the first regiment of what would one day become the U.S. Army Rangers.

In the early fall of 1689, Benjamin Church and his 250 Rangers set out on their first expedition into Acadia. On September 21, Church and his men came upon a group of settlers who had been attempting to establish the village of Falmouth (now Portland, Maine), and who were presently under attack by Wabanaki warriors. Church and his men leapt to defend the settlers but discovered, to their dismay, that the musket balls they had been issued were too large for their guns. After hastily hammering the lead balls into crude cylindrical slugs, the militiamen drove back the natives, incurring 21 casualties in the process. The site at which the battle took place is where Portland’s Deering Oaks Park now stands.

After an unsuccessful attempt to locate hostile Indian encampments deep in the Acadian wilderness, Church and his men retreated to Boston, leaving Falmouth unprotected.

Forward to 1690: The Acadian Theatre.

Richard York

Church and his men retreated to Boston, leaving Falmouth unprotected.

No, the elite in Massachusetts with large amounts of land in Maine wanted to minimize the cost of sustaining soldiers to protect the settlers. Church specifically wrote a letter to the elites saying taking the soldiers out would endanger the remaining settlers. His warnings were ignored. Most of the same elite distracted the people from their involvement by using the Salem Witch Trials. The leading minister, George Burroughs, from Maine was in essence murdered as a witch.