Feb 13, 1950, Eielson Airbase, Fairbanks Alaska: A Convair B-36 bomber (Flight 2075) of the US 436 SAC squadron left the airbase at 5:25 PM for a run to its home base at Carswell Air Force base at Fort Worth, Texas. The flight was to take 16 hours and was to include a “simulated combat profile” mission. The route would take the it non-stop via Washington State and Montana. Here the B-36 would climb to 40,000 feet for a simulated bomb run to southern California and then to San Francisco. It would then continue its non-stop flight to Fort Worth, Texas. Six hours into the flight, something went wrong.

The B-36 was, in its day, the largest production bomber ever built anywhere in the world. In every dimension it was bigger than the B-52, and its wing span of 230 feet was larger than that of a Boeing 747. The B-36B was powered by six pusher-prop engines. Later versions had four jet engines added to the six piston engines. These long range heavy bombers were in service with the US Air Force for about ten years. With the advent of the Boeing B-52, the B-36 was gradually phased out and completely replaced by the year 1959.

Six hours after takeoff from Eielson Airbase, Flight 2075 was experiencing icing conditions and multiple engine fires. Distress messages came in quick succession on the live answering service. The first distress signal came at 11:25 PM. It said the aircraft was in difficulty while flying at 40,000 feet. They were climbing down to 15,000 feet.

A second message reported: “One engine on fire. Contemplate ditching in Queen Charlotte Sound between Queen Charlotte Island and Vancouver Island. Keep a careful lookout for flares or wreckage.”

Apart from having icing problems, the instruments were failing. But soon the problem got even worse: two of the engines had caught fire. A third engine had to be feathered, thus the aircraft was flying at half power. According to the pilot, Captain Barry, the plane was iced up at 15,000 feet. When trying to climb, a fire broke out in No. 1 engine. Two minutes later No. 2 engine burst into flames. The bomber started to lose altitude, dropping at 300 feet a minute. Shortly after a fire started in No.5, and then No. 3 stopped with a plugged line.

The final message from the plane indicated their position as 90 miles south of Prince Rupert. The plane was going to ditch in Queen Charlotte Sound. Before jumping, the radio operator, Staff Sergeant Trippodi, had tied down the transmitter key. A steady signal would enable rescue units to get a quick “fix” on the bomber’s last position. The aircraft was put on auto pilot to fly southwest. After the third of the six engines died, the men bailed out.

Captain H.L. Barry, the pilot who was the last man to jump, landed in a shallow pond on Ashdown Island. The other two pilots, Captains W.M. Phillips and T.F. Schreier were among the missing crewmen. According to Captain Barry, as the crew drifted down on their parachutes, the plane had circled over the island once. It was assumed that the aircraft went down and sunk somewhere in the ocean.

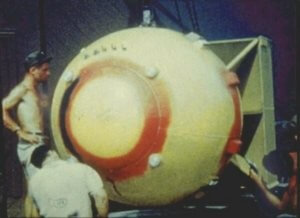

By the morning of February 15, two days after Flight 2075 left Eielson Airbase in Fairbanks, Alaska, five crewmen were lost and presumed dead, a nuclear-capable bomb (The Fat Man was the same bomb used at Nagasaki, Japan in 1945) was lost and the plane itself could not be located.

So what went wrong?

In an interview in 1998 with, Lt. R.P. Whitfield, one of the co-pilots of Flight 2075, the questions was put by Researcher Don Pyeatt.

Q. What was the first indication of problems with the plane?

A. The flight engineers started reporting problems with the fuel mixtures in the engines. They were starting to run full rich. Any attempt to lean them above idle cut off would fail. We then started experiencing multiple failures and none of them could be corrected. Then when the fires started in the engines we knew that we had to make plans for leaving the aircraft.

Q. Could anything have prevented the incident?

A. A follow-up investigation concluded that carburetor icing was the cause. The carburetors in most aircraft are located aft of the engine. This arrangement permits warmed air from the engines to flow around the carburetors and will prevent all but throat icing. In the B-36 with the rearward facing engines the carburetors were in front of the engines and thus constantly subjected to outside air temperatures. The carburetor design consisted of two separate chambers for intake air. The air fed two different sections of the carburetors. There was an opening in the baffle plate that separated the two sections that permitted a pressure balance to be maintained. It was conjectured that this opening became covered with ice and thus caused both halves to always run rich. In addition to this, the warm ocean currents that flow along the coast of B.C. causes heavy fog even in the coldest days of winter. This results in an abundance of moisture in the air above the coastline from which the ice would form. The constant rich mixtures soon caused a build up of raw fuel in the exhaust systems that eventually ignited, causing the fires.

What happened to the fat man bomb?

In the same interview, Whitfield tells us the story:

Q. Describe the crew’s activities after they learned they might bail out.

A. The plane was steadily losing altitude because of the loss of engine power. The flight engineers continued trying to coax the mixtures to no avail. The radio operator tried to report the situation. We knew that we might be heard only by other planes in the area because we were out of radio range of any ground station. We never knew if our transmissions were heard, as we received no response. Capt. Barry turned the plane out to sea so that we could dump the fat man bomb and the dummy core. As soon as we were safely over the sea we dropped the bomb. It was set to airburst at 3000 feet. We were at about 8000 feet when the bomb exploded so we could see the flash as it exploded. One reason for exploding it was to prevent the Soviets from trying to find it later. The other crew members were busy preparing for bailout. They put on their parachutes and removed the observation blisters from the sides of the plane to provide openings from which to exit.

Five crewmen were lost and presumed dead. The speculation was that the first four airmen, Capts. W.M. Phillips and T.F. Schreier; Lt. A. Holie and Staff Sgts. E.W. Pollard and N.A. Straley, out of the plane jumped to close to the BC shore and were blown into the ocean where they died of exposure or drowning.

Of the recovered men, the most critically injured was Radio Operator Trippodi, who was found hanging upside down fouled in parachute. Trippodi had sustained facial and shoulder injuries and, while trying to unbuckle his parachute, got flipped upside down, and there he hung for 12 hours before being rescued by Capt. Barry and co-pilot Whitfield.

In an interview later , Trippodi recalled:

“They managed to get me out of the tree, but I couldn’t walk because of frostbitten feet. So they made me comfortable at the foot of the tree and told me they couldn’t stay with me. They had to go find help for the others, but that they would be back for me.“I lay there in that ice and snow for a day or two until I was found by a Canadian rescue team. who got me to a ship.”

Where did the plane end up?

When the crew bailed out, Captain Barry, aimed the plan southwest and set the autopilot. On June 23, 1956, Doug Craig of Whitehorse, a 22-year-old participating in Operation Stikine, a field-mapping program of the Geological Survey of Canada, found the bomber.

During a traverse of Kologet Mountain, at about 1,650 metres, Craig came upon the remains of the bomber scattered among the rocks and snowfields. These included olive drab cloth and a five-gallon drum attached to a parachute. It also had a pillow on its base to cushion its landing.

Inside was a geiger counter.

The images included with this story come from ” ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STUDY OF CRASH SITE OF USAF BOMBER” written by Doug Davidge in 1998. These include the map of the crash area, a photo of the crash material, a photo of a recovered spare firing mechanism for the Fat Man bomb.

The plane was found 200 miles away from its last reported position and crashed at an altitude almost 2000 feet higher than last reported. It was conjectured that after the bailout the engines restarted and the plane circled in an arc and flew northeast due to an error in the autopilot.

Since 1956 the wreck has been examined by US and Canadian experts and has also been pillaged by souvenir hunters.

Was there ever any danger of a nuclear explosion from the payload of Flight 2075?

The records show that there was no nuclear material aboard 2075. She was carrying a live Fat Man bomb but it had a lead core. The reason they carried the bomb was that the maneuvers they were on required their plane to have the flight characteristics of an actual flight and the weight of the bomb was needed.

Flight 2075 was not the only Broken Arrow reported over Canada. Mysteries of Canada hopes to uncover these added stories over time.

As an interesting final note to this story, consider this. On the flight of the survivors back to Fort Worth, the twin engine Air Force plane carrying the men lost one of its engines, but landed safely.

Ryan

BOOM durham regional police pickering durham regional police oshawa