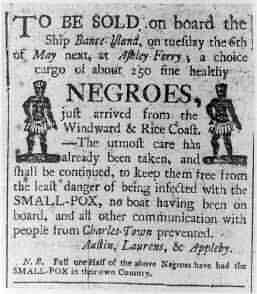

The thought of Slavery is repugnant to us today, but it was not always so. When we hear the word ‘slavery’ today, we most often think of African slaves picking cotton in fields south of the 49th parallel, but that is only part of the picture. Slavery has been part of our human experience as long as we have been humans, and it is, regrettably, still with us today. Slavery was eliminated in Canada in 1834, though it was dying out even before that time for economic reasons.

South of the 49th, American slavery carried on in many states until after the Civil War, and escaping slaves were not safe from ‘slave catchers’ south of the 49th. The goal of an escaping slave was to get to Canada, and thus was formed the “’Underground Railroad”.

The Underground Railroad was a means of helping escaping slaves to move north, to safety. The traditional Spiritual “Follow the Drinking Gourd” dates to slavery times, and was a way of telling escaping slaves to follow the “ Big Dipper” north to freedom. That hymn was but one signpost on the road to freedom, but the signposts on that road were mostly ‘invisible’; they were there, but went unnoticed by most people.

Escaping slaves faced huge problems: they were the wrong colour, they had no ‘papers’, they had no maps, and they could not read. To escape slavery they had to move north, without being seen, mostly on foot, mostly at night. They had to avoid slave hunters who would sell them back to their former masters. They had to find help, but they had to remain invisible.

The Underground Railway is what we now call the loose organization of understanding citizens who helped slaves escape, but it was never a railway. It was a network of compassionate people who did what they could to help others in need.

But still, an escaping slave had to find an Underground Railway ‘station’, and find out where to find the next station. The escaping slave could not be seen, for fear of being caught, they could not speak to the person who was trying to help them, but the slave had to know where to go next.

A code system was developed, a most ingenious code. In those days houses didn’t have central heating, and quilts were piled high on beds every night for warmth. And the quilts would be ‘aired’ outside, on a fence or clothesline the next day.

Some quilts were, in fact, signposts on the Underground Railroad. Some quilts had coded messages within their intricate patterns, messages that escaping slaves could ‘read’ when the quilt was hung out to air.

For example, the “Log Cabin” pattern is a common quilting pattern today, but it has been around for a long time. At one time, it was a signpost, along with the “North Flying Geese” and many other quilt patterns; they helped illiterate slaves move north to safety. Slaves who could not ‘read’ were able to understand subtle messages in the quilts, and that helped them to move north to safety.

To an escaping slave, a “Log Cabin” pattern in a quilt could show that that person was safe in the area, or that they should hide in a building, depending on the patterns used around the Log Cabin. Other patterns include the Wagon Wheel (which might mean hide in a loaded wagon), the Bear Paw (stay off the roads, follow animal paths), and the Star (follow the North Star, also known as the Drinking Gourd).

The story of the Underground Railway is fascinating enough, as Canada was the recipient of most of the travelers. But, where did the travelers settle?

One of the places escaped slaves settled, one northern terminus of the Underground Railroad, is Owen Sound, Ontario. Far north of the American border, and far from the slave catchers, Owen Sound is nestled at the base of the Bruce Peninsula, and has been an important trading center since long before Europeans came to this continent.

Owen Sound and the Bruce Peninsula became home to many escaped slaves, and many of those former slaves became pillars of their communities. Their names live on today in the museums from Owen Sound to Tobermory.

In Owen Sound’s Harrison Park, a cairn commemorating escaped slaves and the contributions they made was unveiled, on July 31, 2004, during the annual Emancipation Picnic. The Emancipation Picnic has been held in Owen Sound every year since 1862; it celebrates the end of slavery in the British Commonwealth (August 1, 1834), and in the United States of America (January 1, 1863).

One prominent escaped slave who settled in Owen Sound was, in fact, born in Canada! John Hall was born in Amherstburg, Ontario, around 1800. He served as a scout forTecumseh’s First Nations warriors during the War of 1812, and was wounded in the leg by bayonet. He, his eleven siblings, and their mother were later ‘captured’ as ‘prisoners of war’ by American soldiers, taken south, and sold into slavery. Hall escaped and made his way back to Canada; he eventually settled in Sydenham (now Owen Sound), where he became the town crier. Hall died in 1900.

Why did so many former slaves travel so far north after crossing the border to freedom? Many went to work, drawn by an industrial boom in Owen Sound and surrounding areas in the 1800s. They built ships and sailed them, they worked on railways, in quarries, and in lumber camps. Some became merchants, some became leaders in business.

Some families remain today, some have disappeared, but the roots of the Black citizens, their presence, and their contributions live on in the many fine museums of Owen Sound and surrounding area.

Note: Webber print is courtesy the Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, No. LC-USZ62-28860

Karen Kociuk

Are there any books available for sale regarding …Owen Sounds role in the Underground Railway