The British Columbia Triangle

Part 1/6

Canada’s Bermuda Triangle

For decades, researchers have observed that people tend to vanish with uncommon frequency in certain triangular regions throughout North America. In 1964, American author Vincent Gaddis used the term “Bermuda Triangle” to describe an area in the North Atlantic where a number of ships and aircrafts have mysteriously disappeared. Lake Michigan is home to the Great Lakes Triangle, an area identified by aviator Jack Gourley in which fleets of ships have vanished with all hands. And there is the infamous Nevada Triangle, a stretch of mountainous desert in the American Southwest that has swallowed over 2,000 airplanes.

In 2019, American author David Paulides may have inadvertently discovered a similar triangle in the Interior Plateau of southern BC, Canada, where an unusual number of hikers have vanished without a trace. In this six-part series, we’ll explore some of the strange disappearances and eerie native legends surrounding this mysterious region in Western Canada- a region perhaps most appropriately dubbed the “British Columbia Triangle”.

Canada’s Dark Side

Canada has enjoyed an international reputation as one of the safest and friendliest countries in the world- a place where crime is low, and where people sleep soundly at night behind unlocked doors. This perception is not unfounded; since its very first Global Peace Index report in 2007, a global think tank called the Institute for Economics and Peace has consistently ranked Canada as the fourth to fourteenth safest nation on the planet.

Despite its glowing reputation as a bastion of safety and security, the Great White North has a few black blemishes where the blanket of benignity enfolding the rest of the country fails to extend. Among the most infamous of these is the so-called “Highway of Tears”, a stretch of the B.C. Highway 16 between Prince George and Prince Rupert, in central British Columbia, on which dozens of female hitchhikers, most of them indigenous, have disappeared since 1970. The turbulent waters of the Great Lakes constitute another scar on Canada’s dark underbelly where entire freighters and their crews have vanished without a trace. From 2007-2019, the Salish Sea, which separates Vancouver Island from mainland British Columbia and Washington, coughed up twenty disembodied human feet encased in shoes, casting a sinister shadow upon Canada’s Pacific Northwest. And there is the notorious Nahanni Valley in Canada’s Northwest Territories, where the headless corpses of prospectors were routinely discovered throughout the 20th Century.

Missing 411

David Paulides is an American researcher and former officer of the San Jose Police Department who has spent the past decade chronicling mysterious disappearances in the United States like those which characterize the aforementioned locales. He has published his findings in ten books and two documentaries which form a series entitled “Missing 411”, “411” being a reference to the phone number for directory assistance in Canada and the United States and a slang denotation for details and information.

In his books and documentaries, Paulides claims that he first began his Missing 411 series following his visit to a certain U.S. national park, during which he was approached by two off-duty park rangers. The rangers, knowing that Paulides was an author, expressed their concern that an alarming number of people were disappearing in U.S. national parks under very peculiar circumstances. They suspected that park officials were aware of the strangeness of these disappearances and were deliberately concealing their inexplicable particulars from the American public.

Following this unsettling encounter, Paulides filed a series of Freedom of Information Act requests to obtain a list of people who had gone missing in the jurisdiction of the U.S. Park Police, hoping to sift through the list to find some of the bizarre cases to which the rangers alluded. The National Park Service responded to each of his requests by claiming that no such list existed- an allegation which Paulides, as a former police officer and detective, found dubious. Paulides then requested that the National Park Service create a list of national parks disappearances for him, as was his right as a published author, and was informed that the service would cost him $1.4 million USD. Eschewing the offer, the author set about collecting information on national park disappearances himself, perusing newspaper archives and scouring the internet in his effort to uncover the dark secret which the National Park Service seemed intent on hiding.

David Paulides’ Profile Points

Throughout the course of his research, Paulides observed that many of the strangest national parks disappearances shared certain unusual characteristics, which he calls “profile points”. The more cases he researched, the stronger this pattern manifested itself. In time, Paulides became so convinced of the significance of these profile points that he neglected to research cases which lacked them. “If the disappearance doesn’t match our profile,” he stated in one of his books, “we won’t look into it.”

The first profile point which Paulides identified is the inability of tracking dogs to follow a scent at the scene of a disappearance. “In nearly 99% of the cases I’ve documented,” he writes in his books, “bloodhounds brought to the point where the victim was last seen cannot find a scent, aren’t interested in tracking, or seem oblivious to the smell. As a former member of a law enforcement SWAT team that had the canine unit attached to our division, I can guarantee that these dogs love their job and relish tracking people… This is one of the most prevalent profile points in the cases we have identified.”

The second of Paulides’ profile points is inclement weather, including “blizzards, fog, rain, snow, hail, dust storms, [and] freezing cold [or] hot temperatures.” This weather often picks up suddenly and unexpectedly following the victim’s disappearance, precluding initial search and rescue efforts.

The third and most mysterious profile point is a scenario in which the body of the missing person is discovered in an area that had been previously searched. “Sometimes the location of the recovery has been searched dozens of times,” Paulides wrote. “In one instance, the searchers had taken the same trail hundreds of times over the week hiking to where they believed the victim was located. On one day of the search, a tree had fallen across the path, and the young victim was found lying on it. Nobody could explain the perplexing scenario.”

Other profile points include missing clothes or shoes; disappearances which take place at twilight; cases in which the missing person suffered from an illness or disability at the time of his disappearance; incidents in which the victim, upon being rescued, cannot recall the circumstances of his disappearance or the period preceding his discovery; cases in which missing people are discovered near creeks, rivers, ponds, or lakes; cases in which people vanish in areas abounding with granite or large boulders; cases in which missing people are discovered in swamps or bogs; cases in which the victim vanished immediately after his companions lost sight of him; and the inexplicable malfunctioning of compasses and other equipment.

In addition to excluding cases which lack at least one of these profile points, Paulides neglected to research incidents in which the victim’s disappearance appeared to be intentional; in which the victim suffered from mental health issues; in which signs of animal predation were discovered; and in which criminal activity occurred in conjunction with the disappearance.

Missing 411: Canada

From 2012 to 2018, David Paulides published eight books in which he documented mysterious disappearances in the United States and Canada which satisfied his specifications. In 2019, he published Missing 411: Canada, the ninth book in his Missing 411 series, which treats exclusively with unexplained disappearances throughout the Great White North. In this book’s Introduction, Paulides claims that several of his Canadian friends assisted him in his research by requesting files on disappearances that took place in Canada’s national parks. Like the U.S. National Park Service, Parks Canada proved uncooperative, and denied most of the requests.

The British Columbia Clusters

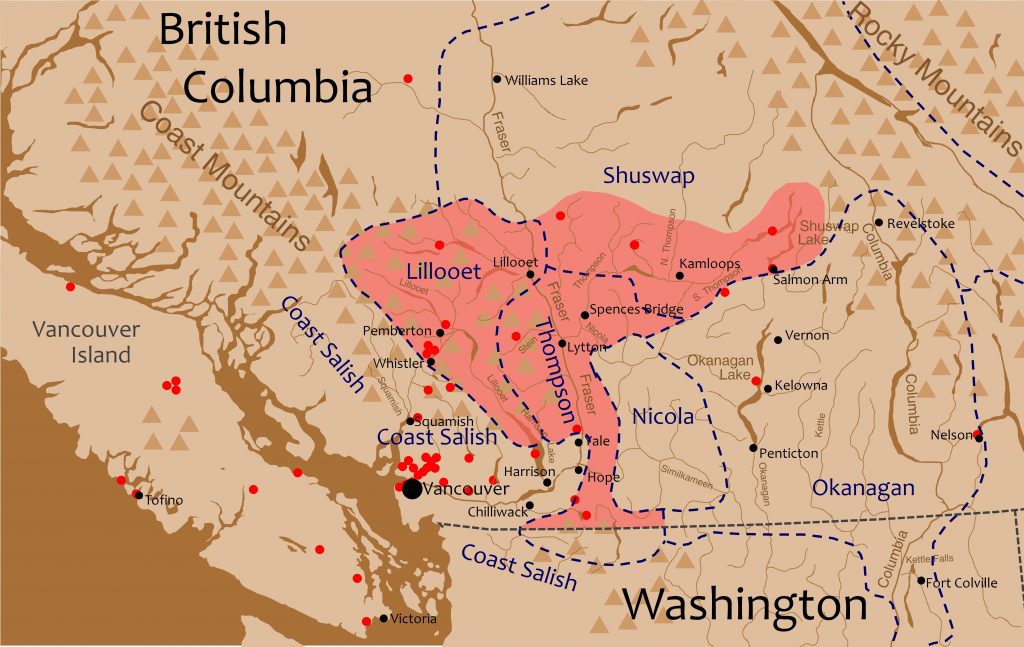

Missing 411: Canada comes with a map of British Columbia, on which most of the British Columbian disappearances outlined in the book have been plotted. In his book, Paulides explains BC’s special treatment by stating, “there is no other province in Canada that comes close to the number of missing people matching our profile points as British Columbia.” Specifically, 40% of the Canadian missing persons cases of which Paulides wrote occurred in “Super, Natural, B.C.,” as Crown tourism corporations often style Canada’s westernmost province.

This appendant document, entitled the “Missing 411 Geographical Cluster Map: British Columbia”, includes five pink dots located in areas with unusually high concentrations of disappearances, which the legend identifies as “clusters”. The westernmost of these clusters lies at the centre of Vancouver Island. Another lies along the Sea to Sky Highway north of Vancouver, in the vicinity of Whistler. The third sits near the town of Hope, at the mouth of the Fraser Canyon, while the fourth cluster is located on the South Thompson River east of Kamloops, near the town of Salmon Arm. Two detailed maps of the Greater Vancouver Area and Vancouver proper, respectively, are superimposed on the provincial map, indicating those areas to be localities of special importance. The map of Vancouver proper bears a fifth pink dot which sits atop Mount Seymour, a mountain and ski resort northeast of North Vancouver.

“Vancouver Island could be a missing person study all by itself,” Paulides writes in his book. The author similarly emphasizes the significance of the Vancouver cluster, stating that “there is no other city in Canada that has the number of missing people within an eighty-mile radius as Vancouver,” and later describing the Greater Vancouver area as “one of the most significant clusters” he has ever identified.

Although he makes no mention of it in his book, Paulides may have inadvertently identified a third mega-cluster deserving special consideration. In the year and a half following the publication of his book, a rash of unsolved disappearances took place within the rough triangle bounded by the clusters in Whistler, Hope, and Salmon Arm. This triangle cuts through the heart of a geographic region known as the Middle Fraser Basin, which encompasses the middle Fraser River, the Fraser Canyon, the valleys of the Lillooet and Thompson Rivers, and Harrison Lake. If the triangle is allowed to conform to the natural contours of the geographic region with which it is roughly congruent, nearly every mysterious disappearance in southern British Columbia outside of Vancouver Island and the Greater Vancouver area took place within it.

The British Columbia Triangle

Before we can delve into the disappearances endemic to this mega-cluster, which is perhaps most aptly designated the “British Columbia Triangle”, we must first define its borders. The clusters identified by David Paulides are nebulous by nature since, in most of the missing persons cases he chronicles, it is impossible to pinpoint the precise location at which the victim went missing. Since the clusters do not have fixed areas, we cannot use them as demarcation points.

We also cannot adopt the boundaries of the Middle Fraser Basin, despite that most of the disappearances which Paulides identified in British Columbia’s southern interior took place within it. The most widely accepted definition of the Middle Fraser Basin places the northern terminus of this geographic region north of the city of Quesnel, well beyond the geographic pattern suggested by the disappearances.

To make matters even more confusing, there is no real consensus as to what constitutes Greater Vancouver, a cluster with which the British Columbia Triangle could potentially overlap; some define this area as the Metro Vancouver Regional District, while others contend that it extends across the Lower Mainland, encompassing the lower Fraser Valley to the east and the Sea-to-Sky Corridor to the north.

Perhaps the most appropriate method by which to define the British Columbia Triangle, for reasons which will become more apparent later on in this series, is to defer to the traditional borders of the Interior Salish First Nations, in whose territories almost every disappearance in British Columbia’s southern interior took place. Specifically, most disappearances appear to have occurred within the ancestral homelands of the Lillooet and Thompson Nations, as well as in the the southerly Bonaparte, Kamloops, and Shuswap Lake Divisions of Shuswap territory.

If we adopt these ancient boundaries, the lower limit of the British Columbia Triangle follows the southerly borders of both the Thompson and Lillooet Nations, which separate these Interior Salish peoples’ traditional territory from that of their Coast Salish cousins. The entire Hope cluster lies within Thompson territory, and therefore within the British Columbia Triangle, although two of the three disappearances of which the cluster is comprised occurred within territory over which both the Lower Thompson and the Skwah or Chilliwack First Nation, a Coast Salish people, have historically laid claim. The Whistler cluster, on the other hand, is split in two; four disappearances took place north of the boundary line, in Lillooet territory and within the British Columbia Triangle, while three occurred south of the line, in Coast Salish territory and in what some would consider the northernmost reaches of the Greater Vancouver area. Although it is tempting to regard these seven disappearances as part of the same cluster on account of their close proximity to each other, as David Paulides did, a natural geological barrier dictates that they be separated into two categories; the four disappearances north of the boundary line lie within the harsher, drier watershed of the Lillooet River, while the three to the south all took place in or south of the humid, coastal Garibaldi Mountains.

The Disappearances

Herman Jongerhuis

November 10, 1957; Monte Lake

The first odd disappearance to occur in the British Columbia Triangle is that of a Dutch immigrant named Herman Jongerhuis, who came to Canada in 1951 and settled in the city of Kamloops.

On the morning of Sunday, November 10, 1957, only a week after attaining Canadian citizenship, 55-year-old Jongerhuis went hunting with his friend and fellow Dutchman, Kees Bulk. The hunters decided to try their luck at Monte Lake, a small body of water situated about 25 miles (40 kilometres) southeast of Kamloops, nestled in a cluster of low mountains called the Monte Hills.

Like most of the Thompson Plateau, the area surrounding Monte Lake is semi-arid, dominated by grasslands and ponderosa pine forests. Some interesting and little-known features unique to this area are deep, narrow, vertical fissures in the surface rock, known locally as the “Bearcat Caves”.

During their hunting trip, Jongerhuis and Bulk decided to go their separate ways, and agreed to meet back at their vehicle at noon for lunch. Bulk made the rendezvous as planned, but Jongerhuis failed to show. After some time had elapsed, Bulk became alarmed and decided to search for his partner.

Although Paulides apparently failed to come across this information in his research, newspaper articles indicate that Kees Bulk headed to the point at which he had last seen Jongerhuis and fired three shots into the air with his rifle, a universal signal of distress. Shortly afterwards, he heard three answering shots in the distance, but was unable to determine the location from which they sounded.

Although Jongerhuis was a competent woodsman, he was not properly equipped to spend a chilly November night in the wilderness; he had brought only a little food with him, along with a few matches, and was wearing light clothing. When the hunter failed to return to the vehicle by sundown, Bulk decided to alert the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP).

A search and rescue operation ensued. By Tuesday, two days after Jongerhuis’ disappearance, forty experienced woodsmen, selected from a group of 70 volunteers, were scouring the Monte Hills for the missing hunter under the leadership of RCMP Constable Jack White. Walkie talkies, tracking dogs, and a helicopter supplemented the search effort.

Several private pilots from Kamloops also assisted the operation by circling the area in their monoplanes. Although their vision was impeded by low clouds, the aviators spotted a plume of smoke issuing from a mountainous, brush-choked area just south of Kamloops. A subsequent investigation yielded nothing of interest.

All throughout the week, an uncharacteristic torrent of heavy rain pummeled the region, transforming the desert-like landscape into a slippery, muddy morass which made travel in the area almost impossible. Despite the obstacles, the searchers, whose ranks had swelled to fifty, made a thorough scan of the area but failed to uncover any clues as to the fate of the vanished Dutchman. As an article in the November 16, 1957 issue of the Nanaimo Daily News put it, “every inch of the ground in the area where Jongerhuis is presumed to have disappeared had been covered several times without revealing a trace of him.”

The searchers were forced to temporarily suspend their search on Friday on account of poor weather. On Sunday, November 17th, seven days after his disappearance, Herman Jongerhuis was presumed dead. The RCMP called off their search, and were outstayed by about half a day by some of the Netherlander’s relatives.

The grim sequel to the vanishing of Herman Jongerhuis appeared in the September 20th, 1960 issue of The Province, a British Columbian tabloid-style newspaper which had covered the search and rescue operation. Three years after the Dutchman’s disappearance, a party of Kamloops hunters discovered a skeleton and a rusted rifle on the shores of Ernest Lake, a tiny body of water located about 11.5 miles (19 kilometres) west of Monte Lake. Police identified the body as that of Jongerhuis. The article claimed that the corpse was discovered 5 ½ miles from the hunter’s last known location.

Betty Jean Masters

July 3, 1960; Red Lake

On the afternoon of July 3, 1960, about two and a half months prior to the discovery of Jongerhuis’ body, a British Columbia man named Maurice Masters, along with his wife and 20-month-old daughter, Betty Jean, set out on a trip to Red Lake, a remote body of water about 35 miles (56 kilometers) northwest of Kamloops. The purpose of the trip was twofold; the couple planned to visit their friends, Mr. and Mrs. Robert Muskett, and conduct some business at the post office next door. The Masters lived on a farmhouse outside Copper Creek, a tributary of the Kamloops River which drains into the latter’s northwestern corner. The drive to Red Lake would have taken them less than half an hour.

Red Lake is a popular fishing destination tucked away in rugged, arid stretch of wilderness heavily forested with lodgepole and ponderosa pine. The lake is fringed by shoreline marsh in which most fishermen report their best luck. Two proximate geographical features, namely Tranquille Peak and the gold-bearing Tranquille River, along with the more distant abandoned Tranquille Sanatorium, are named after an epithet which the Hudson Bay Company’s French-Canadian voyageurs gave to a calm, coolheaded Shuswap chief named Pacamoose, a friend of the celebrated explorer Samuel Black, whose band routinely wintered in the area throughout the 19th Century. In the 1960s, Red Lake boasted a tiny logging community comprised of two lumber mills, a post office, a general store, and a handful of residences.

On that fateful Sunday evening in the summer of 1960, Masters and his wife headed into the post office at Red Lake. They left little Betty Jean outside with two local playmates, the young children of their friend, Robert Muskett. At around 8:00, about an hour before sunset, they came out of the post office and found that Betty Jean was missing. The toddler’s tiny playmates could give no clue as to where the baby had gone.

Masters and his wife began to search for their missing infant, calling out her name as they scanned the area in which the children had been playing. When their preliminary search proved fruitless, the adults enlisted the help of some locals. The party searched late into the evening but failed to find any trace of Betty Jean.

The Masters resumed their search at first light on Monday morning, assisted by regional RCMP officers and over a dozen employees of the two local sawmills, who closed up shop when they heard the troubling news. The rescue party searched all day, without success. Strangely, an RCMP tracking dog brought to the site of the disappearance failed to pick up a scent. An article in the Lethbridge Herald suggested that “the animal became confused in the criss-crossing of tracks.”

On Tuesday morning, the RCMP selected thirty six of the toughest men in the region to assist them in their search and rescue operation, which was supplemented by a tracking dog and a private airplane. According to an article in the July 5, 1960 issue of the Vancouver Times, “police would accept only experienced forest workers and outdoorsmen in top physical shape in the search party for little Betty Jean Masters.” Despite a thorough search covering miles of mosquito-infested wilderness, in which every known slough and unused well was minutely examined, the little girl was not found.

The search and rescue operation continued throughout the week. During the height of the search, over sixty experienced woodsmen were combing the logging roads and forests for any sign of the missing baby.

The RCMP questioned locals, some of whom furnished them with potential leads which inevitably trickled to the press. According to one report, a suspicious-looking man and woman in a copper-coloured car were seen in the Red Lake area around the time of the disappearance; perhaps, some surmised, Betty Jean had been kidnapped by these strangers. Others suspected that the toddler had been snatched by a wild animal. Some sawmill workers had purportedly seen the tracks of a three-legged cougar in the area, while a few local children reported having been approached by a female black bear who had lost her cub, which was often seen hanging around buildings in the hamlet.

On Thursday, a professional game hunter named Jim Farquharson, who was hunting black bear in the area, employed his hunting dogs in the search effort. According to Paulides, the hunter killed both a bear and a cougar and examined the contents of their stomachs, but failed to find any trace of Betty Jean therein.

By Saturday, November 9th, six days after Betty Jean’s disappearance, the RCMP had exhausted all possible leads and decided to call off the search. One frustrated Mountie described the incident as “queer”. Another expressed his opinion that Betty Jean could not have strayed far “without some help”, noting that the region was so rugged that even hardened woodsmen “could proceed only with extreme difficulty”.

An article in the July 11th, 1960 issue of The Province succinctly summarized the tragic episode thus:

“The fate of two-year-old Betty Jean Masters may never be known. It is over a week since she wandered away in rugged bushland 30 miles northwest of Kamloops.

“RCMP have called off a search of the mosquito-infested region, convinced the youngster is no longer in the area. They believe she may have been taken by a wild animal, or carried off by someone, although they doubt the kidnapping theory.”

Geza Peczeli

September 20, 1960; Mount Baldy

Two and a half months after Betty Jean’s disappearance, on the exact day in which Herman Jongerhuis’ skeleton was discovered, another man was found to be missing on the Thompson Plateau.

Three months earlier, in June 1960, a 24-year-old Hungarian immigrant named Geza Peczeli took a job as a shepherd on the slopes of Mount Baldy, a landmark which various newspaper articles placed in the “snow-covered mountain country north of Kamloops”. Paulides identified Mount Baldy as a hill known today as the Mt. Baldy Lookout, located immediately west of the town of Sorrento, on the southern shore of Shuswap Lake’s southwestern arm. A more likely candidate for this obscure landmark, however, is a long, 7,500 foot-tall alpine ridge west of Dunn Peak, located about 54 miles (87 kilometres) north of Kamloops, known today as Baldy Mountain. Now a protected area called Dunn Peak Provincial Park, the area surrounding this landmark contains old-growth forests of Engelmann spruce and interior Douglas fir, along with alpine meadows and marshlands. Baldy Mountain itself was the site of the once-lucrative Windpass Gold Mine, which operated from 1916 until 1939.

On June 26, 1960, a rancher named David Anderson, who hailed from the hamlet of Rayleigh, located just north of Kamloops on the other side of the North Thompson River, hired Geza Peczeli to tend his sheep flock, which comprised 200 head. He showed the twenty-four year old to his new home, an old cabin on the slopes of Baldy Mountain, which was stocked with fuel, non-perishable food, various supplies, and a rifle. Satisfied that Peczeli had everything he needed, Anderson bade the Hungarian farewell and set out for his ranch in Rayleigh, promising to return in two months with fresh supplies.

Anderson paid a late visit to Peczeli on September 6th to see how he was faring. When he was satisfied the Hungarian had settled into his new routine and had things under control, he left him to his lonely business.

On September 20th, Anderson returned to Baldy Mountain a second time, and found that Peczeli was missing. He searched the mountainside for his employee and his sheep and found the latter huddled together in a camp about two miles from the cabin, standing in about eight inches of fresh snow. The Hungarian was nowhere to be seen, nor were there any traces of his footprints in the vicinity. Finding no sign of Peczeli, Anderson headed to Kamloops and reported his disappearance to the RCMP.

An article in the September 26th, 1960 issue of the Vancouver Sun described the search and rescue operation that ensued:

“A 10-man party made up of RCMP and forestry men familiar with mountain woods, and a searching dog set out early today. The team located Peczeli’s rifle and supplies in the cabin, but no indications he had been there recently. The RCMP told the press that they faced blizzard conditions up the mountain that compromised their search efforts.”

An article in the September 27th, 1960 issue of The Province elaborated on the natural obstacles the searchers combatted, saying, “RCMP said blizzard conditions high on Mount Baldy [caused] drifts up to seven feet deep, and the badly broken nature of the area with its many crevasses made searching extremely difficult.” Other articles suggest that the fresh dump of snow increased the risk of avalanche, presenting a dangerous hazard to which the searchers were reluctant to expose themselves.

The Mounties and their volunteers scoured the mountain for four days but failed to uncover any evidence indicating the fate of Geza Peczeli.

Wallace John Marr

November 19, 1962; Yale

The next man to disappear under mysterious circumstances in the British Columbia Triangle was a 30-year-old native of Calgary, Alberta, named Wallace John Marr. An article in the November 23rd, 1962 issue of the Calgary Herald indicates that Marr moved away from Calgary sometime in 1961, possibly relocating in British Columbia.

On Monday, November 19th, 1962, Marr went on a hunting trip with a 40-year-old Shuswap Indian man named Fred Bascoe, who hailed from the Sugarcane Indian reserve outside the city of Williams Lake, British Columbia, situated north of the Thompson Plateau in the heart of Cariboo Country. The hunters decided to try their luck in Yale, British Columbia, an old and dying gold rush town located near the southern end of the Fraser Canyon, generally considered to lie on the line separating the Pacific Northwest from the British Columbian interior.

Marr and Bascoe travelled up a logging road that wound its way into the snowy mountains northwest of Yale. When they had reached a point about five miles from town, the hunters built a fire by the side of the road. While Marr, who was lightly-clad, warmed himself by the fire, Bascoe decided to follow some fresh deer tracks that he had spotted and headed into the woods alone. After following the tracks for about two miles, the native made his way south to the Cariboo Highway (now the Trans-Canada Highway), the main thoroughfare in the Fraser Canyon. When Marr failed to similarly emerge from the bush, Bascoe notified the RCMP.

A handful of RCMP officers and local lumberjacks headed up the logging road to search for Marr. They found the remains of his campfire without difficulty and espied two pairs of boot tracks leading away from the ashes into the woods, one of them evidently belonging to the missing hunter. The search and rescue team followed Marr’s tracks for some time before losing the trail.

The search for Marr continued throughout the week, hampered all the while by snow, rain, fog, and freezing temperatures which had persisted since the weekend. By Friday, the Mounties conceded that there was little chance they would find the missing hunter alive.

Del Chipman, the superintendent of a logging company who had assisted the operation, suggested to the press that Marr might have slipped and fallen into the rain-swollen Yale Creek, a tributary of the Fraser which cuts through the wilderness northwest of the town for which it was named. “It is very wild country,” Chipman is quoted as having said, “and I can’t see how anyone could survive there for five nights.”

An article in the November 23rd, 1962 issue of The Province put Marr’s disappearance into context by alluding to the startling number of hunting accidents that had taken place in British Columbia that year:

“Marr’s disappearance brings to 27 the number of persons who have been involved in hunting accidents in B.C. so far this year. Ten men have been killed, four have been lost, and one man injured by gunshot wounds. One woman was killed and one lost. Four boys have been killed, two were hurt and three boys and a girl have been objects of wide bush searches.”

On Monday, November 26th, one week after Marr’s disappearance, the Mounties decided to abandon the search. The RCMP officers who had participated in the operation informed the press that it was their belief that Marr had likely died after falling over one of the many cliffs that characterize that rugged stretch of wilderness. Whatever the case, Marr’s body was never recovered, and his fate remains a mystery to this day.

At the end of his chapter on the vanishing of Wallace John Marr, David Paulides commented upon the prevalence of his ‘point of separation’ profile point, writing, “It’s amazing how many times hikers and hunters separate, and something happens, and the individual vanishes. I have had several readers tell me that it appears that someone or something is watching these people, waits for the appropriate time, moves in when nobody is watching, and takes these victims, leaving behind nothing.”

Clancy O’Brien

August 20, 1966; Green Lake

About 43 miles (70 kilometres) east of Baldy Mountain and 38 miles (62 kilometres) northeast of Red Lake lies Green Lake, one of the largest bodies of water along the southern edge of what is known as Cariboo Country, nestled in the heart of an idyllic fishing corridor sometimes referred to as the “Land of the Hidden Waters”. Named for its distinctive emerald hue, which is caused by the sunlight’s reflection off the minerals with which it is saturated, Green Lake is the setting of a host of bizarre happenings and unsolved mysteries which have baffled its visitors for over sixty years. One night in 1979, for example, Betty White, a resident of a small community on the lake’s southern shore, saw a huge ball of bright light fly across the water and disappear into the forest on the other side- the most dramatic of the many UFO sightings that she and her children had seen in the area over the years. Similar inexplicable phantom lights were reported with casual frequency by both visitors and area residents throughout the 1960s, ‘70s, and ‘80s. One spring in 1978, a mysterious 150-foot circle of scorched earth in which the rocks had turned chalk white appeared overnight between the lake’s southern shore and the more southerly North Bonaparte Road. Over the years, locals have witnessed freak cyclonic winds create perfectly circular patterns in the marshy vegetation which grows in the shallowest parts of the lake. And throughout the winter of 1974/75, a local man named Greg Irvine and his family came across huge footprints, found strange nests and hair samples, and heard nocturnal noises evocative of the legendary Sasquatch in the woods behind their cabin.

Of all the mysteries surrounding Green Lake, the most disturbing is the disappearance of Clancy O’Brien, a nine-year-old resident of North Vancouver who vanished without a trace on the afternoon of Saturday, August 20th, 1966.

Clancy, his three younger brothers and two little sisters, and his parents, Patrick and Janice O’Brien, had made the five-hour drive from the big city to attend the wedding of Janice’s brother, Dave Livingston, who was to be married in the nearby town of 70 Mile House. On that fateful summer afternoon, friends and family of the groom congregated at the homestead of Dave and Janice’s father, Neil Livingston, who lived on a ranch on the northern shores of Little Green Lake, a tiny appendage to Green Lake abutting the latter’s northeastern corner. While the adults visited inside the farmhouse, Clancy and his six-year-old brother, Tommy, accompanied two of their cousins- fifteen-year-old Johnny Livingston and seven-year-old Alan Devitt Jr.- on an excursion to Olson’s Butte, a hill located about a mile northwest of the ranch, from which all of Green Lake can be seen through the trees.

At about 2:30 in the afternoon, Clancy left the group, planning to return to his grandfather’s house. Contemporary newspaper articles put forth different reasons for his departure. Some contend that he left to retrieve some wieners and bread from his grandfather’s house so that the boys could make fire-roasted hotdogs atop Olsen’s Butte. Others allege that he stalked off following a dispute with one of his cousins. Others still maintain that he disappeared during a game of hide and seek. Whatever the case, when their cousin failed to return after two hours, the boys headed back down the well-beaten trail to the ranch house. Clancy, they learned, was not at their grandfather’s house, nor had any of the adults seen him since the boys first left for Olsen’s Butte.

When it became clear that Clancy was missing, the boy’s father, his grandfather, local sisters Alice Horn and Enid Scheepbouwer, and Enid’s husband, John, set out to look for him on horseback. The riders failed to find any sign of the missing nine-year-old on the trail from the ranch to Olsen’s Butte, and recruited a handful of family members, friends, tourists, and local ranchers to assist them with the search. By nightfall, over a dozen men and women, flashlights and lanterns in hand, were scouring the woods and muskeg around Olsen’s Butte for the missing boy, calling out his name as they tramped through the wilderness. At 5:00 a.m., the search and rescue party returned to the Livingston ranch emptyhanded and exhausted.

Word of the missing child spread quickly throughout southern Cariboo Country, and within a few hours, eighty fresh volunteers- including the crews of two local sawmills and a mining camp- had taken up the search for Clancy O’Brien. Although frantic family members had long since alerted the RCMP detachment from the nearby village of Clinton, the Mounties expressed little interest in the case until Clancy failed to turn up by the early afternoon.

At 3:00 p.m., the RCMP pressed two local bush pilots into service. Later that afternoon, they brought a tracking dog to the scene of Clancy’s disappearance, which they flew in from one of the RCMP kennels in the Great Vancouver area. Neither the pilots nor the dog found any trace of the missing boy.

By Monday morning, the search party had swelled to 150, its ranks including tourists, local sawmill employees, a helicopter pilot, three bush pilots, 25 horsemen, a 30-man search and rescue squad from the northerly city of Quesnel, and army engineers from the Canadian Forces Base in Chilliwack. Under the direction of an RCMP search and rescue unit from Kamloops, the volunteers searched the wilderness northeast of Green Lake foot by foot, marking the areas they covered with red ribbons.

By Wednesday, two hundred and fifty volunteers were wading through knee-high swamps and slogging through the dense pine, spruce, and aspen forests north of Green Lake, keeping their eyes peeled for any trace of the missing child. “Almost the whole town [of Clinton] is locking its doors to join the search for nine-year-old Clancy O’Brien,” one contemporary newspaper article read. The extra manpower proved beneficial; that day, the searchers came across three sets of footprints in the wilderness which the police suspected might belong to Clancy- the first glimmers of hope in the three-day manhunt. When the RCMP tracking dogs showed no interest in the tracks, however, the search and rescue officials dismissed them. “I’ve read about canines exhibiting this behavior hundreds of times,” Paulides wrote in his chapter on Clancy O’Brien, “only to learn later the tracks may have been essential.”

The operation continued without respite through the weekend, with shifts beginning before dawn and extending long into the night. Concerned citizens from communities all across southern Cariboo Country assisted the effort by donating money, food, blankets, and gasoline. Vancouver-based truck drivers who belonged to the Teamsters Union, of which Patrick O’Brien was a member, provided free transportation to over fifty Vancouverites who wished to assist the search. Some well-meaning Canadians even consulted professional clairvoyants from the United States, but to no avail. Despite the long hours they logged and the hundred square miles of ground they covered, the search and rescue workers, as one newspaper article put it, “turned up cowbells, old slippers, bread bags, old guns, and bridle lines, but not one single bit of evidence connected to Clancy.”

Despite that Clancy had been lightly clad at the time of his disappearance, wearing only a t-shirt and a pair of blue jeans, some RCMP officers who participated in the search held out hope that they would find him alive. An article in the Saturday, August 27th, 1966 issue of the Vancouver Sun quoted an anonymous police official, whom a later article indicates might have been Staff Sgt. Thomas Wilde of Kamloops, as having said, “Much of the area is covered with berry bushes… The boy could stay alive and well for a long time eating nothing but these.”

On Sunday, members of the 250-man, 100-horse search party came across a fourth pair of footprints near a small alkali lake, which Clancy’s grandfather, fifty-year-old Neil Livingston, claimed “compared very favorably” with the tread of the running shoes which his grandson had been wearing at the time of his disappearance.

On Wednesday, August 31st, a bloodhound supplied by the North American Guard Dog Service in Vancouver followed what was described as “a strong but unidentified scent” for three miles to the edge of a lake. The following day, the hound began following a pair of footprints discovered on the opposite side of the lake but lost the trail before any significant clues could be found.

On the evening of Friday, September 2nd, thirteen days after Clancy’s disappearance, the RCMP decided to abandon the search, terminating what a Quesnel-based search and rescue team leader later described as “one of the most thorough and extensive [manhunts] ever conducted in [Interior BC]”. Various logbooks indicate that pedestrian searchers dedicated a total of 22,380 hours to the operation, while horsemen logged 4,888 hours, helicopter pilots 19 hours, bush pilots 75 hours, boatmen 62 hours, dogs 370 hours, and vehicle drivers 1,500 hours. Police officials described the case as “uncanny”, baffled that the enormous search and rescue operation they coordinated had yielded so few clues as to the fate of the missing boy. An RCMP spokesperson informed the press that the police had no plans to drag Green Lake, stating that the lake is “very shallow, with no sharp drop-offs into deeper water anywhere…”

Clancy’s father, Patrick, remained in the Green Lake area after the rest of the searchers had left, roaming the wilderness in search of his lost son until September 12th, 23 days after the vanishing.

To this day, the RCMP considers the disappearance of Clancy O’Brien an open case.

Next Week

Next week, we’ll investigate eight more unsolved disappearances from British Columbia’s Interior Plateau in the second installment of this six-part series on the British Columbia Triangle.

Click here for Part 2.

Sources

Herman Jongerhuis

Missing 411: Canada (2019), by David Paulides

Fire May Give Clue to Missing Hunter, in November 13, 1957 issue of The Province

5 Hunters Missing in Cariboo Area: 2 Vancouver Men Who Set Out for Horsefly Never Reached There, in November 15, 1957 issue of The Vancouver Sun

Searchers Still Seek Hunter, in November 18, 1957 issue of The Province

Betty Jean Masters

Missing 411: Canada (2019), by David Paulides

Desperate Kamloops Search On: Outdoorsmen Hunt Baby, in the July 5, 1960 issue of The Vancouver Sun

Volunteers Hunt Child, in the July 5, 1960 issue of The Province

Unusual Leads in Girl Search, in the July 9, 1960 issue of The Leader-Post

RCMP Consider Missing Tot Incident ‘Queer’, in the July 7, 1960 issue of the Nanaimo Daily News

Wilderness Cloaks Fate of Betty Jean, in the July 11, 1960 issue of The Province

Search for Girl Ends, in the July 7, 1960 issue of The Province

Bear Hunter Will Seek to Trace Missing Child, in the July 8, 1960 issue of The Province

Missing Tot is Sought, in the July 5, 1960 issue of the Lethbridge Herald

Geza Peczeli

Missing 411: Canada (2019), by David Paulides

No Trace of Missing Man, in the September 26, 1960 issue of The Nanaimo Daily Free Press

Searchers Comb Mountain for Missing Young Shepherd, in the September 27, 1960 issue of the Vancouver Sun

Shepherd Lost in Snow, in the September 26, 1960 issue of the Times Colonist (Vancouver, British Columbia)

Hungarian Shepherd Missing Near Kamloops, in the September 27, 1960 issue of The Province

Halt Search for Missing Shepherd, in the September 27, 1960 issue of the Nanaimo Daily Free Press

Search for Shepherd Abandoned, in the September 27, 1960 issue of the Vancouver Sun

Wallace John Marr

Missing 411: Canada (2019), by David Paulides

Hunter Missing Near Yale May Never be Found Alive, in the November 23, 1962 issue of the Nanaimo Daily News

Little Hope of Finding Hunter Alive, in the November 23, 1962 issue of the Leader-Post (Regina, Saskatchewan)

Missing Five Days: Hunter Feared Dead, in the November 23, 1962 issue of The Province

Lost in Hills, in the November 23, 1962 issue of the Winnipeg Tribune

Former City Man Missing, in the November 23, 1962 issue of the Calgary Herald

Continue Search for Hunter, in the November 24, 1962 issue of the Nanaimo Daily News

Search Goes On for Lost Hunter, in the November 24, 1962 issue of The Province

‘Hopeless’ Search, in the November 24, 1962 issue of the Calgary Herald

Little Chance Seen Missing Hunter Alive, in the November 24, 1962 issue of the Vancouver Sun

Abandon Search for Ex-City Man, in the November 26, 1962 issue of the Calgary Herald

Search Abandoned, in the November 26, 1962 issue of the Times Colonist

Clancy O’Brien

Missing 411: Canada (2019), by David Paulides

Massive Search on For Boy, 9, in the August 23, 1966 issue of the Vancouver Sun

Search for Boy is Increased, in the August 23, 1966 issue of the Lethbridge Herald

There’s No Sign of Clancy: Just Musket and Hope, in the August 24, 1966 issue of the Vancouver Sun

Massive Search Fails to Find North Van Boy, in the August 24, 1966 issue of The Province

Lost Boy: Hope Dims in Search, in the August 25, 1966 issue of the Vancouver Sun

Hope Fades for Boy Missing in Dense Bush, in the August 25, 1966 issue of The Province

Search and Rescue Team Joint Hunt, in the August 25, 1966 issue of the Quesnel Cariboo Observer

Search Mounts for Missing Boy, in the August 25, 1966 issue of the Calgary Herald

Hope Fades for Missing Boy in Clinton Area, in the August 26, 1966 issue of the Nanaimo Daily News

Police Ask for More Volunteers, in the August 26, 1966 issue of the Vancouver Sun

Hopes Fading for Missing B.C. Youngster, in the August 26, 1966 issue of the Times Colonist

Police Seek Searchers, in the August 26, 1966 issue of the Vancouver Sun

Intensive Search for Boy, in the August 26, 1966 issue of the Leader-Post (Regina, Saskatchewan)

Searchers Find Two; Others Still Missing, in the August 27, 1966 issue of The Province

40 City Searchers Join Hunt for Boy, in the August 27, 1966 issue of the Vancouver Sun

Strangers Lead Search for Boy, in the August 29, 1966 issue of the Vancouver Sun

No Trace of North Van. Boy Missing in Cariboo Country, in the August 29, 1966 issue of the Nanaimo Daily News

Prints Found in Wilderness May Spell Life, in the August 29, 1966 issue of The Province

Hunt Continues for Lost Boy, in the August 29, 1966 issue of the Leader-Post

Police Say It’s “Uncanny”, Find No Trace, Missing Boy, in the August 30, 1966 issue of the Nanaimo Daily News

Berries May Be Keeping North Van Boy Alive, in the August 30, 1966 issue of The Province

Search Continues, in the August 30, 1966 issue of the Vancouver Sun

Still Hope for Boy, in the August 31, 1966 issue of the Vancouver Sun

Boy Missing After Search for 10 Days, in the August 31, 1966 issue of the Edmonton Journal

Little Lost Boy’s Searchers Have One Aim- Resolution, in the September 1, 1966 issue of the Vancouver Sun

Search to be Called Off, in the September 2, 1966 issue of the Vancouver Sun

Clues Lacking in Hunt for Boy, in the September 2, 1966 issue of the Calgary Herald

Search Fails to Find Boy, in the September 3, 1966 issue of the Leader-Post

Search for Boy Missing 14 Days is Called Off, in the September 3, 1966 issue of the Nanaimo Daily News

Search Ends for Missing N. Van. Boy, in the September 3, 1966 issue of The Province

Still Searching, in the September 1966 issue of the Nanaimo Daily News

Log Book in the Search for Lost Boy, in the September 8, 1966 issue of the Quesnel Cariboo Observer

Private Searchers Quit Hunt for Boy, in the September 12, 1966 issue of the Vancouver Sun

Missing Boy File Open, in the January 16, 1967 issue of the Vancouver Sun

Katherine Wood

Where are parts 3, 5 and 6?