Don’t Whistle at Night!

A Canadian Superstition

One of the strangest mysteries I’ve come across in my two years of writing for MysteriesOfCanada.com is the phenomenon of universal folktales- legends inexplicably espoused by multiple cultural groups which have few discernable connections with one another.

The Welsh, the Chinese, and the Aztecs, for example, all told tales of dragons.

The Kwakwaka’wakw, the Blackfoot, and the Ojibwa- First Nations separated by thousands of kilometres of rugged wilderness and nearly ten thousand years of cultural evolution- shared a belief in both giant birds that caused thunderstorms and supernatural horned water serpents- fantastic animals which they claimed were archenemies.

Native peoples from all across North America, the tribes of the Himalayas, and the Aborigines of the Australian Outback all spoke of hairy, manlike giants which left behind huge footprints, had a penchant for stone-throwing, and emitted a putrid odour somewhat akin to the smell of rotten flesh.

The Dene, the Navajo, and the Maya all have legends of heroic twins who defended their ancestors in ancient times…

The ancient Mesopotamians, the Norse Vikings, and the citizens of the Incan Empire all had stories of a Great Flood…

And nearly every culture to ever exist has its own collection of ghost stories.

One legend shared by cultures from all over the world contends that it is unwise to whistle at night. In most versions of the legend, engaging in this practice invites evil spirits to haunt the whistler. Some groups known to have traditionally espoused this superstition include:

- Mexicans, who believe that to whistle at night is to invite the Lechuza (a witch that can transform into an owl) to swoop down, snatch up the whistler, and carry him/her away.

- Turks, who believe that whistling at night will summon the Devil.

- Arabs, who maintain that if you whistle in the night, you run the risk of luring jinns (supernatural creatures of Islamic mythology), or even the dreaded sheytan (Satan).

- The Han Chinese, who believe that whistling at night invites ghosts into the home.

-

Native Hawaiians believe that whistling at night summons the Hukai’po, or “Night Marchers”. The Japanese, who believe that whistling in the night attracts snakes, thieves, or demons called tengu.

- Koreans, who believe that whistling at night summons ghosts and snakes.

- The Siamese of central Thailand, who hold that whistling at night calls evil spirits and brings bad luck.

- Native Hawaiians, who believe that whistling at night invokes the Hukai’po, or “Night Marchers”- the ghosts of ancient Hawaiian warriors. In another version of the legend, nocturnal whistling summons the Menehune (forest-dwelling dwarves).

- Samoans and the Tonga people of the Pacific Islands, who believe that those who whistle at night may be visited by unwanted spirits.

- The indigenous Noongar people of southwestern Australia, who maintain that those who whistle at night attract the attention of the warra wirrin, or “bad spirits”.

- The Maori of New Zealand, who maintain that if you whistle after midnight, the kehua (ghosts and spirits) will whistle back.

Canada is not immune to this internationally-adopted superstition. Over the past two centuries, countless Old World immigrants brought their native folklore with them to the Great White North, and since the earliest days of Vancouver’s Chinatown, many a Chinese, Japanese, Korean, and Vietnamese-Canadian has suffered his/her grandmother’s admonitions against whistling after dark.

Asian-Canadians are not the only Canucks to inherit the whistling legend from their immigrant ancestors. In his 2016 book Creating Kashubia: History, Memory, and Identity in Canada’s First Polish Community, Canadian historian Joshua C. Blank wrote that his ethnically Kashubian grandmother from Barry’s Bay, Ontario, often repeated an old Polish saying regarding this ancient superstition: “Don’t whistle at night; the devil dances on the stove!”

Interestingly, Canada has a few endemic whistling legends totally independent of foreign influence. Although they are not as well documented as their Old World counterparts, a number of Canadian aboriginal groups have their own superstitions cautioning against whistling at night.

According to one Inuit legend, one who whistles at the Northern Lights risks calling down spirits from the aurora. A poem entitled Labrador in Winter, written by Canadian poet Kate Tuthill, colourfully illustrates this belief thus:

The Inuits say don’t whistle

When the Northern Lights are high,

Lest they swoop to earth and carry you

Up to the luminescent sky.

Not all Canadian aboriginal legends regarding whistling at night involve evil spirits. According to one First Nations tradition that decries it, this practice attracts the “Stick Indians”- frightening wildmen of Interior and Coast Salish tradition, which are either hairy Sasquatch-like giants, gaunt cannibalistic Indians, or forest-dwelling dwarves, depending on the tribal affiliation of the storyteller. Most Salish tribes maintain that the Stick Indians communicate using whistles alternating from low to high. According to the Okanagan (a.k.a. Syilx), an Interior Salish people of South-Central British Columbia, whistling at night, especially in the backcountry or on outskirts of civilization, is likely to attract the unwanted attention of a Stick Indian.

The Dene tribes of Northern Canada have a similar wildman tradition, and according to many missionaries and fur traders who spent time among these people in the late 19th and early 20th Centuries, they were terrified of nocturnal whistling. In the words of Hudson’s Bay Company trader B.R. Ross in his 1879 report entitled Notes on the Tinneh [Dene] or Chipewyan Indians of British and Russian America:

“A strange footprint, or any unusual sound in the forest, is quite sufficient to cause great excitement in the camp. At Fort Resolution I have on several occasions caused all the natives encamped around to flock for protection into the fort during the night simply by whistling, hidden in the bushes…”

Another First Nation with a taboo against night whistling is the Kootenay tribe of southeastern British Columbia. According to a Kootenay woman who was interviewed on December 11, 1997:

“Even today you will hear people that are my mother’s age from the reserve say ‘you don’t whistle at night.’ Okay, that’s taboo. They don’t tell you why lots of times. But it’s: ‘don’t whistle at night- the bad spirits will get you- something will get you.’ But if you take that back not so many generations- if you were out in the dark and your enemy’s around, if you’re whistling, they know you’re there. And there you go! It was designed as stories to tell children so that they could comprehend. Okay, don’t whistle because something bad will happen to me. But the parent’s didn’t go on to say: ‘otherwise the Blackfeet are going to get you in the middle of the night’ or something. ‘They’re going to know where you are and get you.’ It’s kind of a way of telling a fairy story but with a practical purpose of protecting your children.”

Fairy tale or not, the superstition surrounding nocturnal whistling plays an important role in several different folk traditions across Canada, adding a few more ethnocultural groups to that list of peoples from all over the world who warn: “don’t whistle at night!”

Source

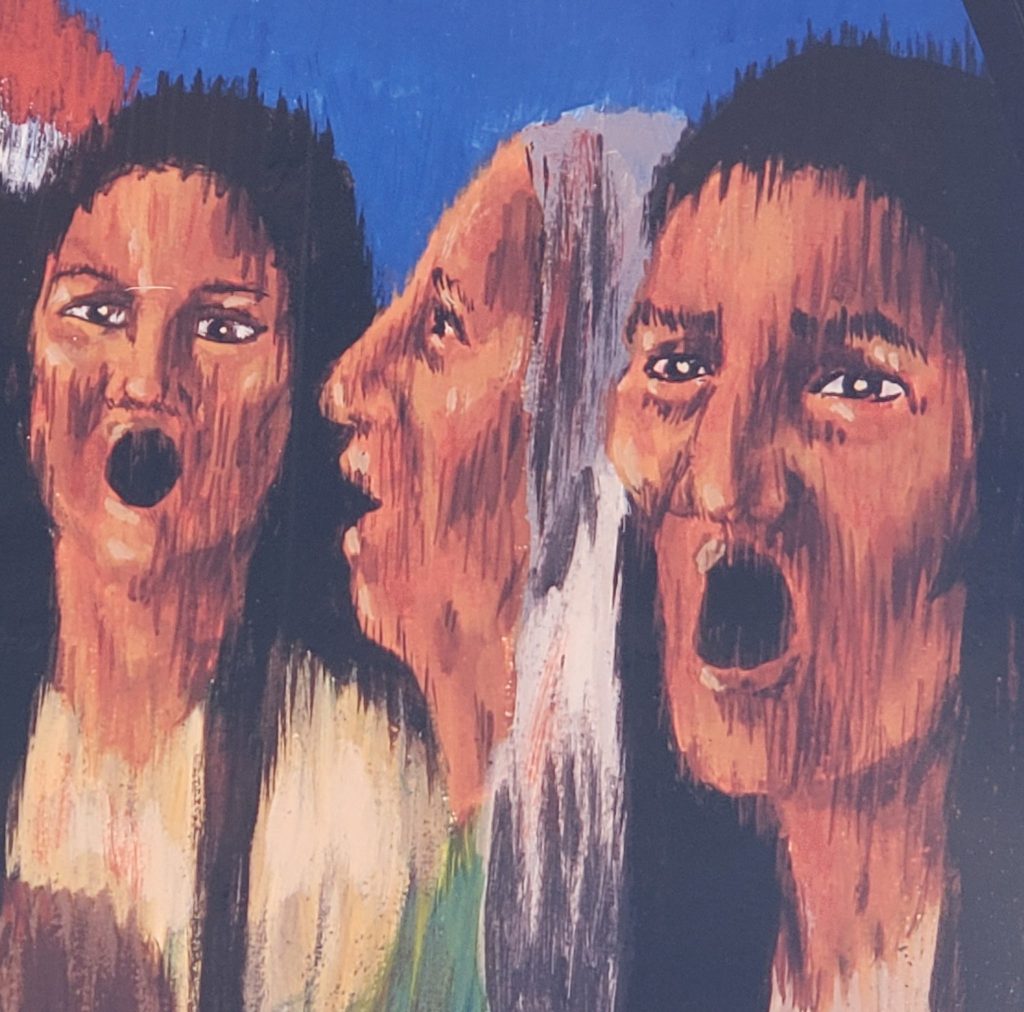

- Feature image: “The Wind”- a carving by British Columbian Nisga’a artist Norman Tait.

Want to Help?

If you enjoyed this article and would like to help support this website, please check out our online bookshop:

vincent abbott

i liked that ,kinda first time known that.

Desiree Vasquez

I don’t know what it looks like . there is a creature with an instrumental like whistle faster than a bullet . strong as can be. It or they are not meant to be encountered alone. God must be in your heart. With out the Almighty one is liable to end up in a casket with another unbelieving camp story. I know not to look at it. Cast it away and stay in the light

Mitchell Taborsky

Actually Fan Tan alley is in Victoria, no Vancouver

Hammerson Peters

Duly noted. Thanks for the heads up.