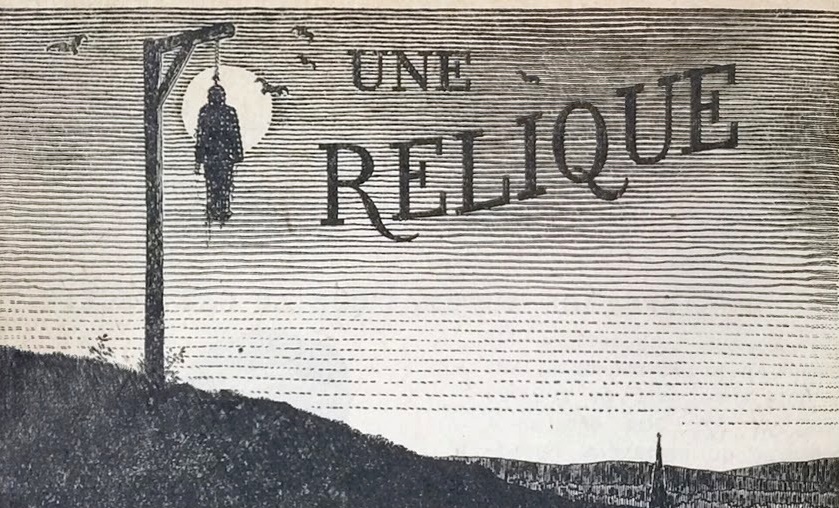

Un Relique: La Corriveau

or

A Relic: The Corriveau

By Louis-Honore Frechette in the 1913 Almanach du peuple de la librairie Beauchemin (English translation)

FROM THE TOP of the Dufferin terrace, in Québec, the eye sees shining in the distance, on the opposite shore, a few miles downstream, a graceful bell tower with lanterns covered in tinplate.

It is that of the small parish church of Saint -Joseph de Lévis, picturesquely sitting on this point of land jutting out into the river, in front of the Montmorency waterfall, facing the southwest end of the Isle of Orléans.

From there, the public road rises gradually towards the west, until it reaches an elevation on which stood, a few years ago, an elegant ionic column surmounted by a golden cross.

It was called the “Temperance Monument”.

There, in the evening, outdoors, novenas were made in time of epidemic, the monthly devotions to Mary; and when Corpus-Christi arrived, it  was at the foot of this column that the rest house was built, where the procession of the Blessed Sacrament ended.

was at the foot of this column that the rest house was built, where the procession of the Blessed Sacrament ended.

We got there by a monumental staircase.

However, a stone’s throw from this place, on the left, there is a fork of paths that was once famous.

Let me tell you why.

In 1849, the year when I followed the preparatory exercises for First Communion in the church of Saint-Joseph de Lévis, I witnessed a very strange event.

One fine morning, two gravediggers – one named Bourassa and one named Samson, if I am not mistaken – were busy digging a grave in the eastern part of the cemetery, which, as in all Canadian regions, was then adjacent to the church.

Suddenly, one of the spades creaked on something metallic. What was it?

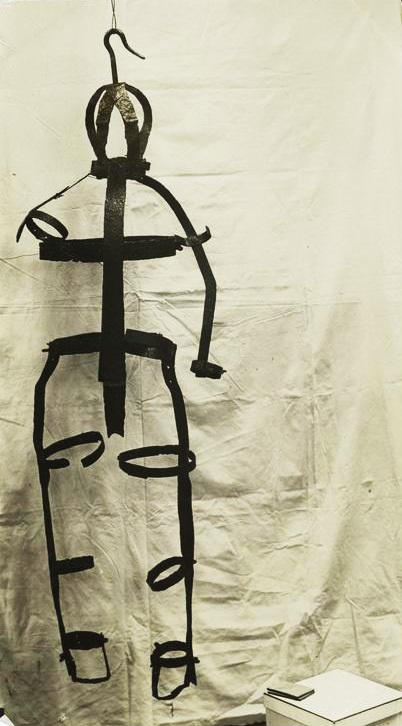

They dug, they upset, they cleared away, and finally they exhumed an iron cage having the exact shape of a horrible human figure.

Although it seemed to have been buried for years, the grim machine was perfectly preserved.

I can still see it.

Barely had the rust broken through the solid stripes of heavy metal and the wrought iron circles of which it was made.

These stripes and circles, strongly linked together by stout rivets, twisted, rolled up, crossed and knotted with art, following, like the frames of a ship, all the contours of the thighs, shins, and torso of what would have been a human body.

These stripes and circles, strongly linked together by stout rivets, twisted, rolled up, crossed and knotted with art, following, like the frames of a ship, all the contours of the thighs, shins, and torso of what would have been a human body.

All was complemented by strong rings around the ankles, knees, wrist, elbows, neck, and waist.

On the top of the head, a large hook with a pivoting base must have been used to hang this singular coffin.

And it was a coffin, no doubt, since it still contained some bones belonging to a woman of remarkable proportions, if memory serves.

Where did this funeral relic come from?

What mystery was contained in this sinister iron network?

The popular traditions preserved by the oldest inhabitants of the place soon resolved the problem.

We had there, before our eyes, a dark witness to the barbarism of another age, the last vestige of a terrible judicial drama which has become legendary to the mind of the people.

We had there, right under our hand, something once gloomily famous, and about which the most fantastic rumors had run, an object which had, for years, filled many a mind with dread, produced nightmares in many a conscience, and which was said to have been kidnapped by the devil and dragged with its contents into the depths of Hell.

This discovery removed a little color from the legend, but on the other hand provided a nice subject for the investigations of historians and archaeologists. Their research went back to the previous century; and, thanks to the traditions supported by certain documents collected here and there, here is what they exuded from oblivion.

Just a hundred years before the date mentioned above – that is to say, 1749 – on a radiant spring day, the small village of Saint-Vallier, located a few twenty miles below that of Saint-Joseph of Lévis, was jubilant.

A joyful crowd, in Sunday clothes, crowded around the parish church, laughing, chatting and joking, to the silvery sound of a bell recently imported from France, and which for the first time, invited the faithful to a wedding mass.

The entire population of the fort – to use a local expression – seemed ready to decorate their houses and to sow flowers on the steps of the church, on the steps of which climbed, arm-in-arm with her father, the prettiest girl of ten parishes around, the shy and blushing bride, Marie-Josette Corriveau.

More than one envious glance greeted the young farmer with a martial bearing who, his arm resting on that of his own father, entered the small church at the same time, the happy winner in a struggle for the palm of which the most beautiful and the richest young men of the district had contested.

But he himself was rich and handsome; and, moreover, he accepted his triumph so modestly that everyone forgave him his happiness. His happiness! During eleven years, one single cloud seemed to alter its serenity.

Unlike what usually happens in Canadian households generally, the young couple lived alone, and the little pink and blonde heads missed their homes.[1]

What strange things were going on between these two lonely spouses? No one ever knew.

One fine morning, the neighbours, surprised, saw the young woman arrive in town, disheveled, out of her wits, and apparently struck with terror.

One fine morning, the neighbours, surprised, saw the young woman arrive in town, disheveled, out of her wits, and apparently struck with terror.

Sobbing, she said she had just found her husband dead in bed.

The deceased was popular; he was sincerely missed, and everyone expressed their deepest sympathies to the young widow.

Her pain seemed so natural that no suspicion arose in anyone’s mind.

However, when she married a second husband- a young man by the name of Louis Dodier- only three months after the death of her first husband, it caused a stir.

The new couple was watched.

But three years having passed without anything out of the ordinary having taken place to confirm them, all the suspicions gradually disappeared… until, on the morning of January 27, 1763, someone found the body of Louis Dodier in his stable, near the feet of his horse, his skull smashed by what appeared at first to be the animal’s iron shoes.

This time, the authorities were informed.

A regular investigation showed that the unfortunate man had not been struck by the studs of a horse, but by an iron fork, which was found near the scene of the crime still stained with blood.

The first husband’s body was exhumed, and it was found that his death must have been caused by molten lead having been poured into his ears – probably during sleep.

New suspicious circumstances followed one after the other, and soon – for the murder of Dodier at least – the evidence piled up so overwhelmingly against the widow that no one had any shadow of doubt about her guilt.

The trial took place before a court martial, the only court then in existence in the country, which had been ceded to England just days after the crime.

Something to remember is that the accused was tried on behalf of the King of England for a crime committed on French territory, and – according to technical expression – against “the crown and dignity of the King of France”.

The evidence, although circumstantial, was conclusive.

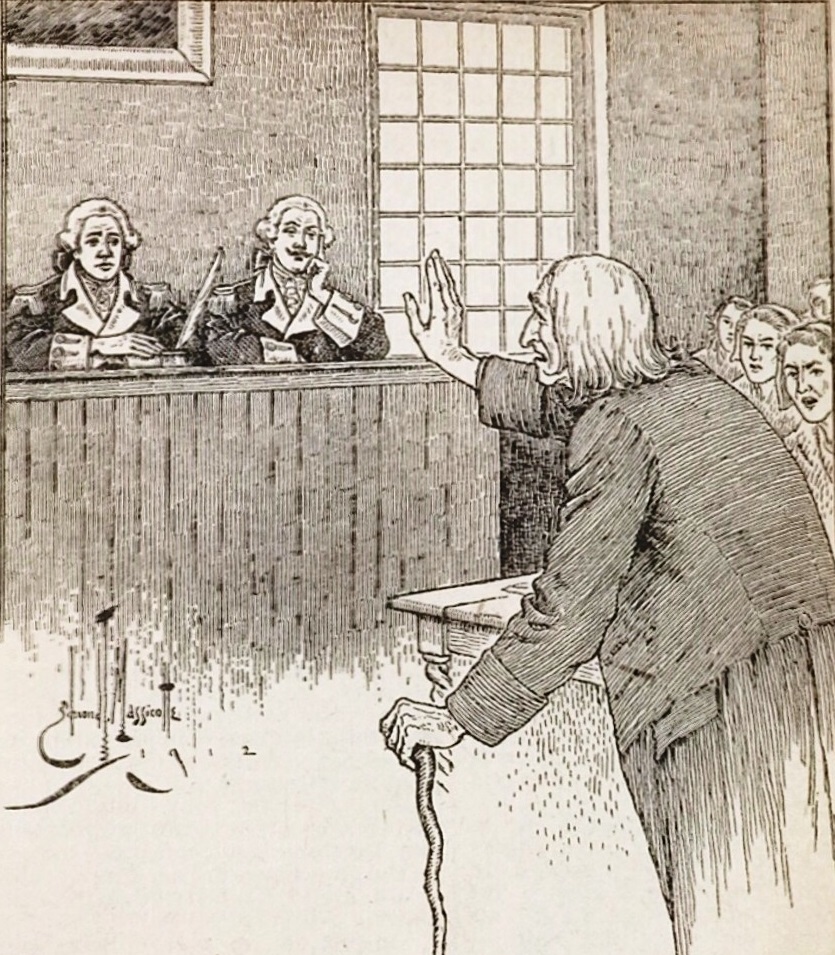

The testimony of a young girl named Isabelle Sylvain above all convinced the court, which was preparing to pronounce the death sentence, when an incident of the highest drama occurred.

An old man with white hair rose from the audience and advanced towards the judges.

“Stop, gentlemen!” he said in a voice shattered by emotion. “Do not condemn an innocent woman. It was I who killed Louis Dodier.” And the old man, melting into sobs, knelt down adding:

“I am the only culprit; do whatever you want with me.”

It was the father of the accused, Joseph Corriveau, who, mad with pain when he saw no other way to save the head of his daughter whom he adored, had just sacrificed himself for her.

We can imagine the effect of this scene. The person who seemed the least affected was the culprit herself; she coldly accepted her father’s sacrifice, and let the supreme sentence fall on the head of this martyr of paternal affection without protesting.

Here is the authentic text of the judgment which was rendered in this famous case. It is extracted from a military document, property of the Nearn family, of La Malbaie. It’s to Mr. Aubert de Gaspé to which we owe this discovery.

Québec, April 10 1763.

General Order.

The Court Martial, presided over by Lieutenant-Colonel Morris, having heard the testimonies of Mr. Joseph Corriveau and Marie-Josephte Corriveau, Canadians, accused of the murder of Louis Dodier, and the trial of Isabelle Sylvain, Canadian accused of perjury in the same cause, the governor ratifies and confirms the following sentences:

Joseph Corriveau, having been found guilty of the crime imputed to his charge, is consequently condemned to be hanged.

The Court is also of the opinion that Marie-Josephte Corriveau, his daughter, widow of the late Dodier, is guilty of complicity in the said murder before the fact, and consequently orders her to receive sixty lashes with nine straps, on the back naked, at three different places, namely: under the scaffold, on the market place in Quebec, and in the parish of Saint-Vallier, twenty lashes at each place, and to be marked on the left hand with the letter M with a red iron.

The Court also condemns Isabelle Sylvain to receive sixty lashes with nine straps on her bare back, in the same way, in the same places and at the same time as the so-called Josephte Corriveau, and to be marked in the same way with the letter P on the left hand.

The old man’s unexpected confession had naturally destroyed the poor girl’s testimony. Her statements were attributed to hatred against the accused.

She was found guilty of perjury, and sentenced accordingly.

As for Joseph Corriveau, bent under the weight of age even less than under the burden of infamy of which he had just voluntarily taken charge, he walked toward the prison, next to his daughter, who, stricken by the joy of having escaped the scaffold, did not even deign to glance at him with pity and gratitude.

The superior of the Jesuits in Quebec was then a reverend father by the name of Clapion. It was he who was called to the condemned man. After having received the old man’s confession, the priest made him understand that, even supposing that he had the right to sacrifice his life and to defeat the ends of justice, his conscience did not allow him to punish and dishonor the poor young girl, Isabelle Sylvain, for a crime she had not committed. The heroic old man was a Christian; he would gladly have walked on the scaffold to save his daughter, but he could not sacrifice his soul. The truth was revealed to the authorities, whose sentiments towards the murderer became all the more implacable, seeing that she had cowardly consented to see her old father undergo the ultimate punishment for a crime of which she alone was guilty. A new trial took place, and here is the text of the judgment; it is drawn from the same sources as the preceding document:

Québec, Avril 15 1763.

General order,

The Court Martial, chaired by Lieutenant-General Morris, is dissolved.

The General Court Martial, having tried Marie-Josephte Corriveau, accused of murdering her husband Dodier, found her guilty. The governor (Murray) ratifies and confirms the following sentence: – Marie-Josephte Corriveau will be put to death for this crime, and her body will be chained and suspended in the place that the governor thinks he should designate.

Signed, THOMAS MILLS.

La Corriveau – to use the name that tradition has given her – has long passed since she was locked up alive in the famous iron cage, and many people are still under the impression that she died of hunger.

They are mistaken.

She was first executed in the ordinary way, that is to say hanged on the Plains of Abraham[2], which, three years prior, was the setting of the famous battle which conquered a territory larger than the whole of Europe for the dying King George II.

After the execution, this singular enclosure was forged around the victim’s corpse, and the whole thing was suspended from the arm of an immense gibbet which was erected on the heights of Levis, at the crossroads of which I spoke earlier.

We can understand what a subject of terror this frightening exhibition was for the inhabitants of the place and for the passers-by. This corpse, surrounded by iron, which the birds of prey and night came to shred, which lamentably stretched its grotesque arms to the horizon, and which swayed in the wind, creaking on the rusty hook from which it depended, was soon the subject of a thousand black legends.

We can understand what a subject of terror this frightening exhibition was for the inhabitants of the place and for the passers-by. This corpse, surrounded by iron, which the birds of prey and night came to shred, which lamentably stretched its grotesque arms to the horizon, and which swayed in the wind, creaking on the rusty hook from which it depended, was soon the subject of a thousand black legends.

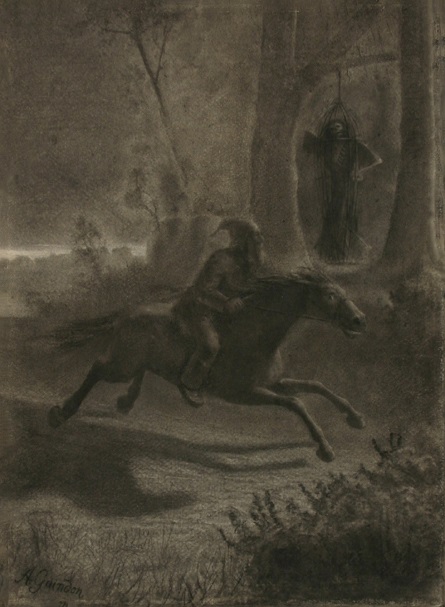

La Corriveau descended from her gallows each night and pursued unwary travelers.

On the darkest nights, she plunged into the graveyard, and, iron-clad vampire, she satiated her horrible appetite on the inmates of the newly-dug graves. The corpse of everyone who died without receiving the sacraments belonged to her by right.

All the doors were locked at sunset.

If it happened that a traveler stopped on the road to gaze upon the spectre, the ground he touched became cursed, and accidents of all kinds multiplied there, until the blessing a priest came to ward off the curse. Under the gallows, the grass was still burnt to the roots.

Les ames en peine[3] met there, and devilish patrols sometimes held interminable sarabandes[4] there.

Several trustworthy people had seen great black beasts lying there, whispering appalling secrets into the corpse’s ear. They were dreadful werewolves who were said to be asking for marriage.

In former times – so the stories go – especially on Saturdays, at the stroke of midnight, the gallows stopped creaking, and one could see some formidable phantom- God knows what- glide awkwardly in the dark night and advance along the cemetery wall, making a sinister clatter of chains and old iron with each step it took. Those who were still watching crossed themselves with trembling hands and knelt to stammer out a De Profundis.[5] It was la Corriveau on her way to the Witches’ Sabbath with the wizards of the Isle of Orleans. At daybreak, she returned to her post, and the gibbet resumed its dismal creaking.

In former times – so the stories go – especially on Saturdays, at the stroke of midnight, the gallows stopped creaking, and one could see some formidable phantom- God knows what- glide awkwardly in the dark night and advance along the cemetery wall, making a sinister clatter of chains and old iron with each step it took. Those who were still watching crossed themselves with trembling hands and knelt to stammer out a De Profundis.[5] It was la Corriveau on her way to the Witches’ Sabbath with the wizards of the Isle of Orleans. At daybreak, she returned to her post, and the gibbet resumed its dismal creaking.

It couldn’t last forever.

One morning, la Corriveau did not reappear. Life is full of surprises. Word spread that the horrible contraption had been taken away by the devil. There was even a faint smell of sulfur in the atmosphere.

The truth is that la Corriveau was not only a subject of consternation for the neighborhood; it had also become a scarecrow for strangers. The inhabitants of Saint-Michel, Saint-Charles, Saint-Gervais and other parishes down the river no longer dared to go to Pointe-Lévi, and came by water to carry their food and do their shopping in Quebec. This caused considerable harm to the small traders and innkeepers of the place.

Self-interest got the better of fear. Some daring fellows, less superstitious than the rest of the population, had detached the cage from the gallows overnight, and had buried it with its contents along the perimeter wall of the cemetery, in a small space reserved for the criminals and the nameless drowned. As was to be expected, the matter was kept secret for fear of the authorities.

In 1830, when the parish church was destroyed by fire and rebuilt, the cemetery was enlarged on this side; this explains the presence of the strange relic in the interior of the consecrated enclosure.

Quite naturally, the press being unfamiliar at the time with Marie Corriveau’s true history, public rumor had considerably enlarged its proportions. It was soon no longer only two individuals whom la Corriveau had murdered. The husbands increased so well in number that when the cage was exhumed before my eyes in 1849, I remember having heard that la Corriveau’s victims numbered seven or eight, with great detail given as to their age, their character, their profession, and especially the certain tragic circumstances which accompanied their deaths.

One can imagine the crowds of visitors attracted by this curious discovery. It lasted a couple of weeks.

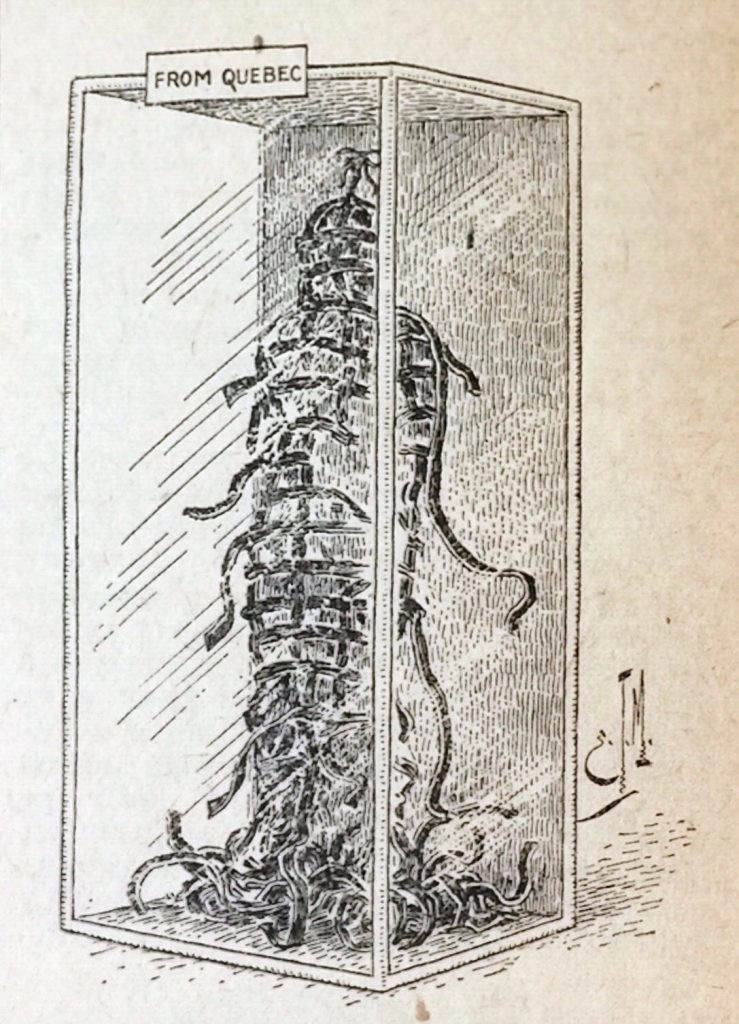

But, one fine morning, we noticed that la Corriveau’s cage, which had been kept locked in the basement of the sacristy, was again gone. The devil had taken it off again. But the devil, this time, was called P.-T. Barnum. Now those who visit the Boston Museum can see, in a corner little frequented by the public, an oblong showcase placed vertically, where, piled up in disorder, lies a mass of old scrap metal, broken, twisted, tangled, and eaten away by rust and fire. On the upper part of the frame, a small sign bears this inscription:

From Québec.

This is all that remains of the famous cage de la Corriveau.

Footnotes

[1] The couple had no children.

[2] The Battle of the Plains of Abraham, a major battle of the Seven Years’ War, fought on September 13th, 1759, in which Great Britain captured the city of Quebec from France.

[3] Literally “suffering souls”; the souls of suicides which, according to French folklore, are condemned to walk the earth after death.

[4] A Spanish dance with Moorish origins; similar to a waltz.

[5] Literally “Out of the Depths” in Latin; Psalm 130, an appeal to God from one in great distress.

Leave a Reply