Back to The Riders of the Plains.

The following is an excerpt from The Riders of the Plains: A Reminiscence of the Early and Exciting Days in the North West (1905), by Cecil Edward Denny. This work is in the public domain.

Continued from Chapter XIX – A Strange Adventure.

Chapter XX

Troubles with the Sioux

COLONEL MACLEOD, WITH myself and escort, proceeded to the Blackfoot Crossing to pay the Blackfeet and Sarcees. At this payment a good deal of trouble was caused at first by the head chief, Crowfoot, who was dissatisfied at the Bloods not being paid with the Blackfeet. He also pretended to think that they should receive the same amount, $12, per head, as at the first payment, although it was understood, by all that after the first year $5 each, except the chiefs and minor chiefs, was to be the amount. However, after a great deal of time wasted in talk, the payment was satisfactorily made, and I proceeded to Morleyville, and paid the Stonies, with whom I had no trouble.

An extract from Colonel Macleod’s report of 1878 on this payment is as follows: “At the Blackfoot crossing things were at first different, the Indians expressing their dissatisfaction at only receiving $5 per head this year, instead of $12, as they did last year. I had a long talk with Crowfoot, the head chief, and his band, the morning after y arrival. It is very evident to my mind that they are instigated to express their discontent by interested persons, who have been visiting them, and who should have known better. However, when they found that I had come there to carry out the terms of the treaty, and not alter the old one, or make a new one, they all came forward and received what the government had promised them by the treaty of last year. Several of the chiefs came and apologized for what Crowfoot had said on the first day of our meeting, and they all sent a message to say that they were perfectly satisfied with everything. The evening before I left I paid a visit to the head chiefs, and I was much gratified to hear them express the contentment which prevailed throughout the camp. Early in the morning, as I was leaving the camp, Crowfoot and several other of the chiefs came to say goodbye. Crowfoot taking me by the hand said: ‘We have come to shake hands with our old friend, and hope he will forget the words I spoke the other day.’

“I entrusted Sub-Inspector Denny with the payment of the Stoney Indians, and enclose his report, from which it will be seen that the duty was most satisfactorily performed.”

I returned to Macleod after this payment, and received instructions to return to Calgary, and take command of that post, with about 50 men. A herd of cattle for distribution among the Indians came in that year, but as the Indians were not prepared to take them over, as the most of them had, after the payments, gone south to hunt, the cattle were turned over to herders. This stock was herded in the Porcupine hills, near the present Pincher Creek, where the police had established a farm with the intention of breeding the mares belonging to the force. This farm was only kept up for two years, as it was not found to pay, and took too many of the few men we had to run it. The herd of cattle was eventually divided up among the Piegan and Stoney Indians; none of the other tribes would take them, and showed no desire to go into stock raising. The Piegans and Stonies have done well with these cattle, and a number of individual Indians have to-day quite respectable herds. But the Bloods and Blackfeet even to-day will not take them, preferring to live on the government rations, and do little or no work.

While I was at Fort Macleod a curious incident occurred. I.G. Baker and Co. supplied us with what beef we wanted, driving down what cattle they required to slaughter from the vicinity of Pincher Creek, near which place they ranged unherded. In butchering a cow it was discovered that the paunch contained considerable coarse gold, and on washing it out, about $20 in very coarse gold was obtained, mixed with a black sand. This discovery caused quite a stampede of men to that section of the country in which the cattle had been feeding, but nothing that paid was discovered, although in all the creeks and rivers color was found, though not in paying quantities. It has always been a mystery where this gold came from, as he animal no doubt either licked it up in some salty place, or had it in its stomach before it was driven from Montana.

No gold has as yet been found on the eastern slopes of the mountains in the Territories, although color can be found in all the streams, and, as in the North Saskatchewan, in paying quantities. As you go up that river towards the mountains it gets scarcer in quantity. The country as yet has been little prospected, and I think that in time gold will be found, particularly in the ranges of hills, such as the Porcupine hills near Fort Macleod.

The fall and winter of 1878 was passed quietly at Macleod and Calgary, as nearly all the plain Indians had gone south into Montana after the buffalo. This was indeed the last year that any large number of buffalo were to be seen in the North West Territories, although they did not entirely disappear for a few years afterwards. In fact, all game, with the exception of geese, ducks, and grouse, had nearly disappeared, the deer and elk being now only found among the mountains, and rarely seen along the rivers. A few bears would during the summer season be sometimes seen along the river bottoms, but with the exception the game was practically driven out.

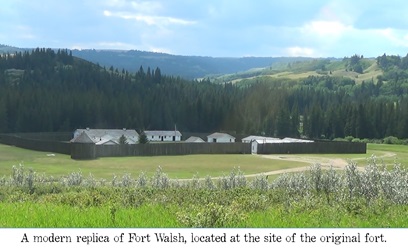

Our work, therefore, as most of the Indians were away, was this winter easy, although patrons had to be continually made up and down the different rivers. At Fort Walsh, however, there was plenty of work, as the Sioux at Wood mountain were troublesome, and many Indians of other tribes congregated there, so that much care had to be taken to keep peace among them all.

Our work, therefore, as most of the Indians were away, was this winter easy, although patrons had to be continually made up and down the different rivers. At Fort Walsh, however, there was plenty of work, as the Sioux at Wood mountain were troublesome, and many Indians of other tribes congregated there, so that much care had to be taken to keep peace among them all.

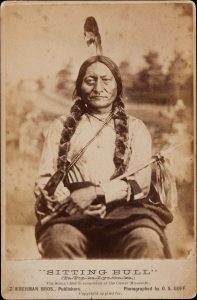

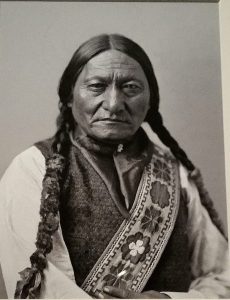

A small stockade fort had been built at Wood mountain, and a troop of police stationed there. This place is only a few miles from the American boundary, Fort Bufard on the Missouri river being the nearest American post. The Sioux Indians, under Sitting Bull, when they first came into Canadian territory after the Custer fight, numbered soe 150 lodges, with about eight souls to the lodge. They were much crowded when they first came over. The fact of these Indians, hostile to the United States, finding secure shelter on our side, soon had the effect of drawing to that camp numbers of dissatisfied Indians belonging to that tribe, until about 600 lodges were camped around Wood mountain, and the number of buffalo killed by this tribe was enormous. They committed many depredations along the Missouri river, and much trouble was the outcome of their sojourn in the country.

An extract from the commissioner’s report on the arrival of Sitting Bull and his Indians, states as follows: “At that time the savage warfare that these Sioux Indians had engaged in against the United States was fresh in the minds of American settlers. The press teemed with graphic descriptions as to the doings of the savages, whose presence caused such consternation among the settlers and intending immigrants. Their power and warlike dispositions was quoted again and again. Recollections of the Minnesota massacre were publicly revived, and large numbers of American troops were hurried forward and posted along the Western frontier. It was not to be wondered at that when the Sioux crossed over into Canadian territory general uneasiness prevailed.

“Not only were the fears of our actual and intending settlers aroused, but our own Indians and halfbreeds looked with marked and not unnatural disfavor upon the presence of so powerful and savage a nation in their midst. We were assured on all sides that nothing short of an Indian war would be on our hands. To add to this, serious international complications at times seemed inclined to present themselves. Both the American and Canadian press kept pointing out the possibility of such a state of affairs coming about, the press of Manitoba even urging that a regiment of militia be sent to the North West to avoid international complications, and the interruption of trade.”

From the above it will be seen the position in which the police force was placed from 1877 until 1882, in which year the Sioux surrendered to the United States government, and left our country for good. A perpetual supervision had to be kept over them, and we were kept in a constant state of anxiety and watchfulness during these years, to say nothing of the hard service that had to be performed both in the summer and during the long and severe Northwest winters. When it is remembered that the force at Wood mountain only consisted of 50 men, in a poor wooden stockade, which a war party of Sioux would have had no trouble in taking in an hour, the courage and tact of the police is beyond all praise. Many a critical occasion arose in dealing with the Sioux, and only by sheer pluck was a massacre of that small force avoided.

One instance I remember that occurred the winter previous to the surrender of Sitting Bull. Major Crozier was in command of the small force stationed at Wood mountain. Sitting Bull and his camp were getting pretty hard up for food (the buffalo being about gone) and were most persistent in their endeavors, backed up by threats, to obtain rations from the police, which were, of course, always refused. They were therefore in a savage mood. They had always been hostile towards the Canadian Indians, particularly the Bloods and Blackfeet.

The Blackfeet would always come to our posts when near them, and many of them were scattered all over the country on the look out for any stray buffalo that might still remain. A Blood Indian had strayed as far as Wood mountain, in a starving condition, and was making for the police fort when the Sioux got wind of him, hunting him like a pack of hounds. He evaded them by hiding in the thick brush, and managed to get to the fort at night, seeking protection, which was promised him. The Sioux, on hearing that he was in the fort, flocked there in hundreds. The gates being closed on them, they did not enter. They demanded his surrender, and threatened if it was not complied with to burn the fort and kill everyone in it. This they could have done, being some thousands strong. Everything was got ready for defense, and Major Crozier went to the wicket gate alone to parley with Sitting Bull himself. For hours he stood there and argued with him, and finally on Sitting Bull trying to push his way into the fort, he took him by the shoulders, throwing him out, and shutting the gate.

The Blackfeet would always come to our posts when near them, and many of them were scattered all over the country on the look out for any stray buffalo that might still remain. A Blood Indian had strayed as far as Wood mountain, in a starving condition, and was making for the police fort when the Sioux got wind of him, hunting him like a pack of hounds. He evaded them by hiding in the thick brush, and managed to get to the fort at night, seeking protection, which was promised him. The Sioux, on hearing that he was in the fort, flocked there in hundreds. The gates being closed on them, they did not enter. They demanded his surrender, and threatened if it was not complied with to burn the fort and kill everyone in it. This they could have done, being some thousands strong. Everything was got ready for defense, and Major Crozier went to the wicket gate alone to parley with Sitting Bull himself. For hours he stood there and argued with him, and finally on Sitting Bull trying to push his way into the fort, he took him by the shoulders, throwing him out, and shutting the gate.

An attack was at once expected, but the firm front shown overawed even these fierce Indians, and they returned to their camp with many threats. The Blood Indian was smuggled out that night, and a horse given him, and he was soon well on his way west. He reached Fort Walsh with his scalp intact, thanks to the courage of that small band of police, and their brave commander. This was one of the many hazardous chances taken by the officers and men of a force only 300 strong, in the old days of the opening up of the now prosperous and fast settling up North West Territories.

Continued in Chapter 21- Famine Among the Blackfoot.

Leave a Reply