This article was originally published on my personal website in 2014.

The Legend of the Lost Lemon Mine

One of the greatest mysteries of the Canadian Rockies is the legend of the so-called “Lost Lemon Mine.” As is typical of Western Canadian legends, there are a number of contrasting, mutually exclusive and seemingly irrefutable versions of the story. Some versions are tales of murder, madness and Indian curses, while others tell of outlaws, robberies and Indian massacres. In spite of their differences, however, all versions of the legend agree on one thing: that there is a wealth of lost gold hidden somewhere on the eastern slopes of the Canadian Rocky Mountains. Over the years, a number of enterprising prospectors have spent considerable time and resources in search of the lost gold, each one believing whole-heartedly in his own version of the Lost Lemon Mine tale. Mysteriously, many of these prospectors’ expeditions ended in tragedy and disaster. Their versions of the legend, along with a number of other credible versions, are described below.

Lafayette French’s Story

Background

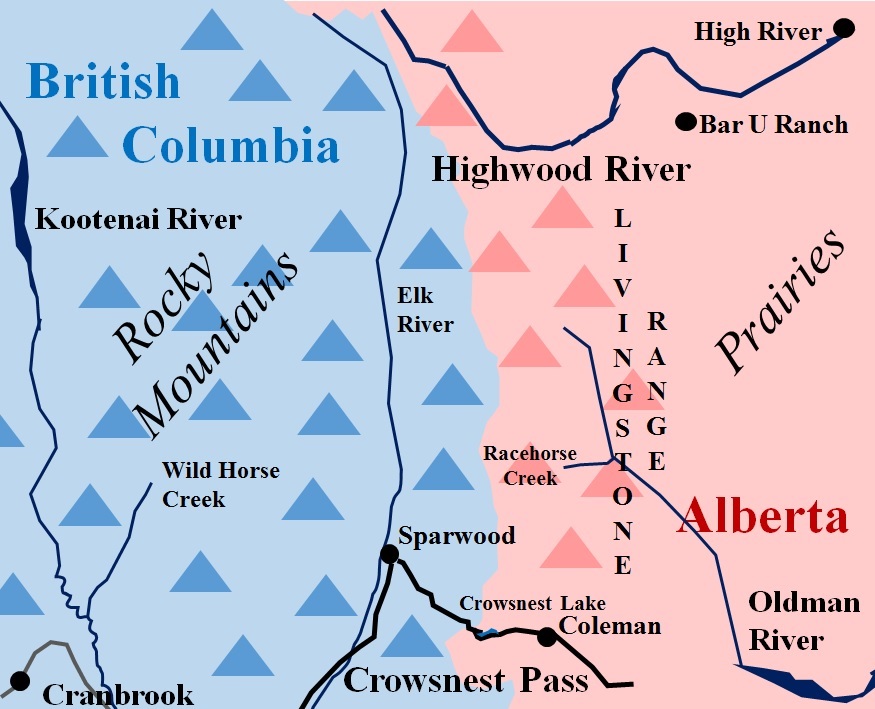

Lafayette French was an adventurer and entrepreneur born in Pennsylvania in about 1840. After working for the Standard Oil Company in the 1870’s, French headed northwest to the Canadian plains and became a buffalo hunter and Indian trader, establishing posts both at Blackfoot Crossing and on the Highwood River near present-day High River. In his later life, French, along with his partner Orville Hawkins Smith, would become one of Alberta’s first ranchers. Before French came to Alberta, the Canadian- specifically British Columbian- Rockies had already been subject to several gold rushes, namely the Fraser River Gold Rush of 1858, the famous Cariboo Gold Rush of 1861-67, and the Wild Horse Creek gold rush of 1864. Upon his arrival in Alberta, French, like so many other American-Albertans before him, came down with a bad case of gold fever. He frequently outfitted prospecting parties, and spent many a summer himself prospecting in the mountains, searching in particular for the fabled Lost Lemon Mine. French’s story of the Lost Lemon Mine was first told by Senator Daniel Edward Riley in 1946. Born in 1860 in Baltic, Prince Edward Island, Riley was a Maritime schoolteacher who moved west to Alberta in 1882 in search of adventure. In 1883, he met and entered into what would become a lifelong friendship with Lafayette French, then his part-time employer who, over the years, told and retold Riley his tale of the Lost Lemon Mine. In later years, Riley became a successful rancher, an insurance and real estate agent, the mayor of High River, and eventually a member of the Canadian Senate, and would often stake French in his summertime searches for the lost gold. In the spring of 1946, two years before his death, Riley had French’s version of the tale published in the Alberta Folklore Quarterly. His retelling of French’s story- which was echoed and considerably supplemented in an article by Tom Primrose, a former reporter and editor for the Calgary Herald and the High River Times- is arguably the best known version of the tale.

The Story

In the spring of 1870, a group of Montanan prospectors set out from Tobacco Plains- a prairie-like section of the Kootenay River (sometimes called the Tobacco River in the United States) in southeastern British Columbia and northwestern Montana that stretches from Grasmere, BC (about 45 kilometers south of Fernie, BC), to Eureka, Montana- to pan the North Saskatchewan River for gold. Among the party was a man known as Blackjack- the prospector who discovered the gold that launched the Cariboo rush in British Columbia; widely considered to be the best prospector in the West- and his partner Lemon. After some fruitless panning on the North Saskatchewan, Blackjack and Lemon decided to return to Tobacco Plains. For protection against the Blackfoot, who frequently slaughtered prospectors, they joined a group of half-breeds bound for Fort Stand Off, and then split from the group to follow an old Indian trail up High River into the mountains. According to Freda Bundy, a pioneer historian, this Indian trail may have been the old Stoney (Nakoda) pack trail that followed the Racehorse Creek through the Racehorse Pass and eventually into the Elk River Valley (the Elk River flows into the Kootenay River, which leads to Tobacco Plains). When they reached the headwaters of the stream- which, according to a crude map supposedly drawn by Lemon, was actually the confluence of three separate streams- the two men panned and, to their delight, discovered that the riverbed was rich in gold. Shortly thereafter, they stumbled upon the source: a rock ledge streaked with solid gold.

That night, Blackjack and Lemon got into a heated argument over whether they should settle on the location and mine as much as they could carry, or return to spot in the spring. The exchange became so intense that the two partners nearly came to blows. Eventually, the two livid prospectors, without resolving the argument, decided to retire for the night. Blackjack slowly nodded off while Lemon, wide awake, lay fuming. When he was sure that Blackjack was asleep, Lemon quietly slipped from his blankets, crept over to his sleeping partner and split Blackjack’s head with an axe. When he realized what he had done, Lemon was overwhelmed with panic. Resolving to abandon the camp at first light, he built a huge fire and started to pace back and forth, rifle in hand, brooding fearfully. As he did so, he began to hear ghostly moans and other hideous lamentations faintly superseding the crackling of the fire. Horrified, Lemon feared that he was being haunted by the spirit of his murdered partner. Slowly, he began to descend into borderline insanity, a state from which he would never fully recover. Unbeknownst to the terrified prospector, the ghastly wails were being issued by two young Stoney braves, William and Daniel Bendow, who tormented the unsuspecting Lemon from concealment in the brush. The Indians had been stalking Lemon and Blackjack for some time, and had witnessed their discovery of the gold, their argument and Blackjack’s subsequent murder. At dawn, the half-crazed Lemon set out for Tobacco Plains. Upon his departure, the two Stoneys took what valuables they could from the camp and headed to the Stoney village at Morley, Alberta. The braves told their story to Joseph Bearspaw, chief of the Bearspaw band (the Stoney Nation is composed of the Bearspaw, Chiniki and Wesley bands). Wary of the implications of a gold rush on Stoney land, the chief swore the two braves to secrecy. After several days, Lemon arrived at Tobacco Plains and sought out his friend, a priest. During his subsequent confession, he showed the priest a sample of the gold-rich rock from the mine he and Blackjack had discovered. Immediately, the priest sent out John McDougall, a Metis, to Lemon’s mine. The mountain man found the location without much trouble and buried Blackjack’s remains, erecting a stone cairn over the grave. As soon as he left for Tobacco Plains, a group of Bearspaw’s men, who had been secretly keeping watch over the spot, destroyed the cairn and all evidence of human activity.

The following spring, a party of miners, having heard of Lemon’s find, convinced Lemon to lead them to the mine’s location. Try as he might, however, the mentally fragile prospector was unable to retrace his steps. After a fruitless search, the miners began to believe that Lemon was deceiving him, and they confronted him accordingly. In response, Lemon became violently unhinged, and had to be restrained and escorted back to Tobacco Plains. After that incident, Lemon went to live on his brother’s ranch in Texas, where he remained until his death. After the failed expedition, the priest from Tobacco Plains took it upon himself to reclaim the mine. The next year, in 1872, he outfitted a party of miners who were to be led by John McDougall, the half-breed frontiersman who had buried Blackjack. The party headed to Crowsnest Lake and waited for McDougall, who was at Fort Benton, Montana, at the time. When he had finished his business at Fort Benton, McDougall set out to meet the party. En route, he stopped at Fort Kipp, a notorious whiskey fort in Southwest Alberta, and indulged in the fort’s most infamous commodity, a dangerous rotgut pseudo-whiskey frequently sold to Indians. During his night at Fort Kipp, McDougall drank himself to death, taking the secret of the mine’s location to his grave. The mining expedition was subsequently cancelled. In 1883, the priest, undaunted, outfitted another mining party and sent them to search for the mine. Unfortunately for the miners, a forest fire that charred the area earlier in the year made the terrain impassable. The party was forced to return to Tobacco Plains.

In the spring of 1884, the priest send out yet another party to search for the mine, this one once again led by Lemon. However, the closer Lemon got to the mine’s location, the more deranged he became. Once again, the party was forced to abandon the project. Dismayed, the priest cut his losses and gave up his search. After another unsuccessful search in the spring, led by a man named Nelson who had panned with Blackjack and Lemon on the North Saskatchewan, Lafayette French arrived in Alberta and took up the torch. During his expedition into the mountains, French contracted some mysterious ailment and returned home, grievously ill. For the next 30 years, French searched for the Lost Lemon Mine. Despite the assistance he received from members of the previous priest-outfitted searches, and from members of the Metis band that had escorted Blackjack and Lemon from the North Saskatchewan River to the old Indian trail, French was largely unsuccessful. The longer French searched, the more he got the impression that some sort of curse plagued those who sought the gold, or at least those who got close to finding it. This disturbing notion never presented itself more starkly than in a string of instances that began near Pincher Creek and ended in High River. One cold winter day, a party of Stony Indians led by William Bendow, one of the two Stoney braves who had witnessed Blackjack’s murder and the discovery of the mine, took shelter on a ranch near Pincher Creek, Alberta. The ranch belonged to a pioneer named William Samuel Lee, who was a friend of Lafayette French. French, who was coincidentally visiting the ranch at the same time as Bendow, fed the hungry Indian and his followers. When French asked Bendow about the lost mine, the Stoney became uncharacteristically tight-lipped and refused to disclose any information. That spring, French presented Bendow with 25 horses and 25 cattle, and promised to give them to the Stoney on the condition that he bring him to the Lost Lemon Mine. Initially, Bendow agreed, and it was arranged that the party would head out in the morning. However, by morning, the Indian was racked with some superstitious terror and refused to lead French to the mine. The enterprise was subsequently abandoned. Early in the winter of 1912, at French’s insistence, William Bendow once again agreed to lead the prospector to the mine. He and his band were en route to Morley, and he promised to lead French to the location of Blackjack’s murder once French could get George Emerson- a prospector, rancher and former fur trader- to accompany them. That night, Bendow died suddenly and mysteriously. The Stoneys, convinced that Bendow had brought bad medicine upon himself by agreeing to reveal the tribe’s secret, loaded the Indian’s body into a Red River cart and brought back to Morley for internment. On the night of their return, Bendow’s son-in-law died in the same mysterious manner. French, who was already outfitted by Senator Riley, decided to proceed with the expedition, even without Bendow. On that expedition, which was to be his last, the treasure hunter made an important discovery. When he returned from the mountains, French stopped by the famous Bar U Ranch in the Alberta foothills. In an obvious state of excitement, he wrote a cryptic letter to a friend at Fort Benton, stating that he had located “it” and would explain everything when he had the opportunity. After mailing the letter, he rode further west, deciding to make camp at an old log cabin about two miles from the E.P. (Edward Prince) Ranch (at that time the Bedingfield Ranch) in High River. Sometime that night, the cabin mysteriously caught fire- a strange incident in light of French’s considerable expertise. French was severely burned, but managed to escape with his life and crawl two miles in the snow to the Bedingfield Ranch for aid. By the time the frontiersman reached the ranch, it was morning, and the ranch hands were already in the field. French, wounded and exhausted, crawled into the bunkhouse, hauled himself into one of the bunks and passed out. That evening, after supper, as the cowboys sat around playing cards in the bunkhouse, a strong voice emanated from one of the bunks: “A little less noise, gentlemen, please, there is a very sick man in this bunk.” The startled cowhands immediately found French, bundled him into a wagon and brought him to the nearest hospital in High River. By the time he reached the hospital, French was in grave condition. The dying prospector immediately requested to see Senator Riley. “I know all about the Lost Lemon Mine now,” he disclosed to his old friend. French, who had lost much of his strength, promised to tell Riley the rest of the story in the morning. However, he never had the opportunity. French died that night, taking the secret of his discovery to the grave.

Analysis

Ron Stewart’s Theory

Many detractors of this version of the Lost Lemon Mine base their skepticism on the fact that, for years, industrial geologists and seasoned prospectors alike have maintained that no gold of any significance could possibly be found on the eastern slopes of the Rocky Mountains. However, one particular geologist named Ron Stewart- who wrote a well-researched book, The Mystery of the Lost Lemon Mine, on the different theories and accounts behind the Canadian legend- challenges that prevailing theory. Stewart explains that about 100 million years ago, it is entirely possible that low concentrations of gold carried by the lava flows that would become the Crowsnest Volcanics dissolved into the salty, acidic water frequently associated with volcanic eruptions. This gold solution could have travelled and come into contact with the limestone that characterizes the eastern slopes of the Rocky Mountains. The more basic limestone may have neutralized the acidic solution, causing the gold to be deposited in the rock. Blackjack and Lemon, Stewart surmises, may have stumbled upon a particularly rich deposit. Stewart’s theory is supported by the evidence gleaned from his own samples of Crowsnest Volcanics from the Crowsnest Pass area; his samples were found to contain invisible dissolved gold- a discovery which made newspaper headlines around the world.

Hugh Dempsey’s Theory

Hugh Dempsey, an acclaimed Albertan historian, made an effort to reconcile Lafayette’s story with hard historical evidence in the Frontier Book #4- The Lost Lemon Mine: The Greatest Mystery of the Canadian Rockies. In his research, Dempsey unearthed two nearly identical newspaper articles from 1870 and 1886 that appear to tell tales strikingly similar (albeit far less dramatic) to French’s account.

According to the articles, in 1868, an American named Frank Lemmon (spelt with double ‘m’s) was one of a 30-40 member prospecting party that was searching for gold throughout western Alberta. The party was making their way to Fort Edmonton when they intercepted a different southbound party. Lemmon and his partner, Old George, joined this southbound party and travelled with them until they reached the site of present-day Nanton, Alberta. At this location, the partners separated from the group and travelled west towards the mountains, hoping to find a mountain pass that led to the Wild Horse Creek gold fields.

The two men found a pass, travelled to the west side of the Rockies, and panned for gold. At the head of a creek, Lemmon and Old George discovered promising concentrations of gold dust. Here, the two stories diverge. One tells that, shortly after discovering the gold, Old George was killed by Blackfoot warriors while Lemmon narrowly escaped with his life. The other story maintained that Lemmon shot Old George in the heat of an argument. In any event, Old George was killed, and Lemmon travelled alone south to Jocko (St. Ignatius) Mission south of Flathead Lake.

The two men found a pass, travelled to the west side of the Rockies, and panned for gold. At the head of a creek, Lemmon and Old George discovered promising concentrations of gold dust. Here, the two stories diverge. One tells that, shortly after discovering the gold, Old George was killed by Blackfoot warriors while Lemmon narrowly escaped with his life. The other story maintained that Lemmon shot Old George in the heat of an argument. In any event, Old George was killed, and Lemmon travelled alone south to Jocko (St. Ignatius) Mission south of Flathead Lake.

In the summer of 1870, Lemmon convinced a group of miners to accompany him to the site of his discovery. Lemmon led the group through the mountains to what he claimed to be the gold-bearing creek. It quickly became apparent to the other miners, however, that Lemmon was lost. When they challenged Lemmon and the veracity of his claim, the prospector broke down and promised that he would do his best to find the stream. For days, Lemmon led the party on a fruitless search through rough terrain until, finally, the miners gave up and returned home.

Hugh Dempsey suggests that this version of the story was the true version, which was significantly embellished by Father Jean L’Heaureax, a fake priest. L’Heaureax was a French Canadian seminary student who fled southwest to Montana in search of gold after being involved in a scandal. At first, L’Heaureax passed himself off as a legitimate priest. However, when he was found out, he joined a band of Blackfoot and performed the functions of a priest and interpreter for many years. Reputed to be a strange man, L’Heaureax had a history of perpetrating gold-related hoaxes that led, in at least one case, to a false gold rush. Dempsey theorizes that L’Heaureax may have heard Lemmon’s tale and altered it, painting himself into the story as a priest from the Jocko/ St. Ignatius Mission (and placing the mission not in the Flathead country south of Flathead Lake, but rather in the geographically similar Tobacco Plains 180 kilometers to the northwest) , and including the name Blackjack- a well-known prospector who made a name for himself in the Fraser River and Cariboo Gold Rushes; who likely met L’Heaureax in Fort Edmonton in 1866- into the story for added spice.

According to Dempsey, history shows that L’Heaureax and Lafayette French were both camped at Blackfoot Crossing in 1877. Dempsey suggests that L’Heaureax may have told his embellished tale of the Lost Lemon Mine to French during this period. French, in turn, told the tale to his friend Dan Riley, who turned it into the legend we know today.

King Bearspaw’s Story

Background

In Lafayette French’s story of the Lost Lemon Mine, as told by Senator Dan Riley, two Stoney Indians witnessed Blackjack’s murder and reported the incident to their chief, Jacob Bearspaw. The chief, not willing to risk a gold rush in Stoney territory, swore the two braves to secrecy. Unlike the mysterious Lemon and Blackjack, Jacob Bearspaw has a very clear place in Albertan history. He was a Stoney chief who had a son named Moses (who became chief of the Bearspaw Stoneys after Jacob’s death) and a grandson named King (Moses’ son). According to King, Jacob disclosed the secret location of the gold only to his brother, and to his son Moses. King, contrary to French’s account, also claimed that Jacob’s other brother had in fact witnessed Blackjack’s murder, and was therefore also privy to the location of the gold. King made no secret of his desire to find the gold and use it as any white man would. His father, Moses, believed that gold was an evil thing that would corrupt his son, and so he never told King where he could find it (although King claimed that he once accompanied his father to a location in close proximity to the mine). Although his grandfather Jacob told him nearly everything there was to know about the mine, King, due to his self-professed desire to use the gold, was never entrusted with the secret location by either of his patriarchs.

The Story

In 1921, King Bearspaw, equipped with the information given to him by his father and grandfather, decided to devote himself entirely to the search for the Lost Lemon Mine. He forfeited his rights as a treaty Indian in order to freely search the backcountry, thereby relinquishing the considerable degree of economic security that his Indian status afforded him. For more than 70 years, King- along with Jack Hagerman, a well driller and mechanic who was the only white man King trusted well enough to work with- searched for the lost mine. King was very secretive about his work. According to Tom Primrose, a writer for the Calgary Herald, King once admitted to finding “color”, or gold dust, in the mountains in a location that was not the Livingstone Range (the generally accepted location of the mine). In 1979, the 89 year old King Bearspaw, the last living link to the lost mine, passed away, taking his secrets with him.

A Supporting Tale

King’s case is particularly intriguing because it apparently debases Hugh Dempsey’s very convincing and historically-backed argument. Demspey, using evidence from period newspapers, suggests that Lemmon and Blackjack merely found gold dust on the west side of the Rockies, and not a bonanza on the east side as was told in French’s story (the source of which was likely, according to Dempsey, Father L’Heaureax’s embellished tale). However, it seems very unlikely that King Bearspaw- who learned the tale of the Lost Lemon Mine from his grandfather Jacob Bearspaw, a primary source- would have spent a lifetime prospecting the eastern slopes of the Rockies in a self-professed quest for the lost gold if Dempsey’s theory was true. According to Tom Primrose, King Bearspaw subtly suggested that Lemon’s mine was not located in the Livingstone Range as so many others believed, although he never revealed where he believed the actual location to be. The following accounts of Colin Thompson and Arthur Cantin may shed some light on this mysterious alternative location. Colin Thompson was an ex Hudson’s Bay Company employee and pioneer who built a homestead in what is now Red Lodge Provincial Park, near Bowden, Alberta. One stormy winter day in 1894, two Cree braves, along with eight pack horses, came knocking on Thompson’s door seeking refuge. The homesteader promptly took the travellers in and sat them down by his wood stove, where he shared a meal with them and a trapper named Henning, who was also visiting at the time. Grateful for Thompson’s hospitality, the Indians opened up to the frontiersman and shared their story. That winter of 1894 had been a particularly brutal one for their band of Cree. Without enough stored food to last through the winter, the Cree were forced to subsist on rabbits and grouse and whatever small game they could find. Soon, the Indians, especially the babies and the elders, began to starve. In an effort to save his people, the band’s chief called upon the two braves who now sat by Thompson’s fire and sent them out to acquire supplies at the trading post at Bowden. They had been travelling for eight days and- cold, hungry and exhausted- were grateful for Thompson’s assistance. Thompson, noting that the braves lacked the furs that would be necessary for trade, asked the Indians if they planned to sell their packhorses. The Cree answered that they would need the packhorses to carry supplies back to the camp. Thompson told the braves that the traders at Bowden were not known for their charity towards Indians, and would not give them anything for free. It was in that moment that one of the braves procured two buckskin sacks filled with raw gold ore, saying that he was certain the white traders would accept it. Upon seeing the gold, Thompson and Henning inquired as to its source. The Indians, wary of the white man’s lust for gold, replied that it came from a sacred valley near an Indian burial ground. The gold from the valley, they said, was only to be used in extreme circumstances, such as the one the Cree found themselves in that winter. When Thompson and Henning pressed the Indians further, the Cree were reluctant to disclose any more information. They promptly thanked Thompson for his hospitality and disappeared into the blizzard, bound for Bowden. Arthur Cantin, a Lost Lemon Mine enthusiast, believed that the sacred valley the Cree spoke of in Thompson’s account was the site of Lemon’s gold. This theory is not necessarily incompatible with French’s version, as the Cree and Stoneys- staunch allies within the Iron Confederacy- might certainly have venerated the same holy valley. Cantin further speculated that Blackjack and Lemon might have followed an old Indian trail that led south from Rocky Mountain House into the mountains. Acting on his theory, Cantin conducted a number of prospecting expeditions in the Rockies. By pure happenstance, a friend of Cantin discovered what appeared to be a long-abandoned mine entrance in a valley west of Bowden in Red Lodge Provincial Park while hunting for bighorn sheep. The hunter, aware of his friend’s theory, showed Cantin his find. With an overgrown trail and the confluence of three streams, the valley matched French’s description of the Lost Lemon Mine. At the time of the discovery, it was avalanche season. Wary of the curse that had supposedly claimed the lives of French and Bendow, Cantin decided to postpone his investigation of the cave until a safer time. The following year, Cantin returned to the valley. To his dismay, he discovered that an avalanche had destroyed the Indian trail that ran from the valley to the mouth of the cave. Without climbing equipment or a helicopter, Cantin never succeeded in entering the cave. During a later discussion with a Red Lodge Provincial Park Ranger station in the area, Cantin learned that King Bearspaw had been prospecting in that very same valley for more than twenty years.

The Outlaw Story

Background

In 1961, Neil Nichoson- a rancher, World War II veteran and former officer of the North West Mounted Police (served from 1900 to 1905)- wrote a version of the Lost Lemon Mine story that is now archived in the Glenbow Museum in Calgary. Nicholson heard this version of the legend from four frontiersmen named William Olin, John Nelson, Mort Holloway and William Lee. This same version of the legend was retold by Sam Livingstone (a prospector and trader who became one of the first farmers in the foothills near Fort Calgary; dubbed Calgary’s first citizen), Jimmy White (a prospector and miner who worked in Fort Steele, British Columbia; whose tale was documented by Arthur Cantin), and John Hunter (a.k.a. Chief Sitting Eagle, a Stoney resident of Morley, Alberta; whose tale was documented by Calgary newspaperman Fred Kennedy).

The Story

According to this version of the Lost Lemon Mine tale, Blackjack and Lemon were prospectors in the Wild Horse Creek gold rush of 1864. After meeting with little success, the two partners committed a string of murders and robberies throughout the goldfields of the east Kootenays, acquiring a fortune in stolen gold. The miners whom Blackjack and Lemon swindled immediately formed a posse and pursued the outlaws, who had no choice but to flee east through the mountains. Shortly thereafter, on the eastern slopes of the Rockies, a disoriented Lemon was discovered by a party of Stoneys from the Highwood River area. According to Nicholson, the Stoneys were en route to their annual summer congregation with their allies, the Kootenay Indians. The prospector claimed that he and his partner Blackjack had been ambushed by Blackfoot warriors, and that Blackjack had been killed. Sure enough, the Stoneys found Blackjack’s corpse nearby with a bullet in his back. Although they could never prove it, some of the Stoneys suspected that Lemon may have murdered his partner. After his chance meeting with the Stoneys, Lemon traded some gold nuggets for provisions and, after receiving directions from the Stoneys, proceeded south to Fort Benton, Montana. The prospectors who told this story believed that Lemon buried his fortune of stolen gold somewhere on the eastern slopes of the Rockies. Although Lemon returned several times to reclaim his gold, he was never able to find his cache.

Cloud Walker’s Story

Background

On January 5, 1960, a Metis midwife and herbalist named Florence Kroesing had an article published in the Lethbridge Herald. Her story, which she learned from her mother, may hold the key to the location of the Lost Lemon Mine.

The Story

One summer in the late 1890’s, a weary and bedraggled Blackfoot woman and her 11-year-old son rode out of the woods and onto a homestead near present-day Coleman, Alberta, in the Crowsnest Pass. The lady of the house, Florence Kroesing’s mother, took in the rundown Indians and nursed them back to health. While Kroesing’s mother doctored the two Indians, the Blackfoot woman, whose name was Akkoskun, or Cloud Walker, told her story. Cloud Walker was from the Blood Reserve near Cardston, Alberta. Earlier in the year, a man named Jack Lemmon (spelt, as in Hugh Dempsey’s newspaper articles, with two ‘m’s) and his partner rode into the reserve to purchase supplies for a trip into the mountains. After purchasing moccasins and pemmican from the Bloods, Lemmon also decided to buy Cloud Walker, a widow, for two horses and a woolen Hudson’s Bay Company blanket. The Blood chief married Lemmon and Cloud Walker that same day. Before sundown, Lemmon, his partner, Cloud Walker and her son left the reserve and made camp on the St. Mary River. The following day, they travelled northwest until nightfall and made camp near Lee’s Lake (named after the same William Samuel Lee from Lafayette French’s account). On the third day, the party entered the Livingstone Range in the Rocky Mountains. Eventually, the party came to an unfinished cabin deep in the wilderness, at the foot of a low mountain. That night, Cloud Walker prepared a simple, solid meal of pemmican and bannock. After finishing the meal, Lemmon and his partner retreated to the unfinished cabin, where they had stored their provisions. Cloud Walker and her son slept in separate teepees. For the next couple of months, Lemmon and his partner panned a nearby creek. While the men worked, Cloud Walker and her son kept busy chopping firewood, cooking, cleaning, repairing clothes, sewing moccasins and smoking the venison that Lemmon occasionally brought back to camp. Every day, Lemmon returned with some gold dust, and every morning he showed Cloud Walker where he hid it- inside a buckskin pouch, which he wedged into a secret hole beneath one of the floorboards of the cabin. One day before heading out to pan, Lemmon instructed his wife to build a corral for the horses a short distance from the cabin. Using poles and brush, Cloud Walker did as her husband requested. That evening, Lemmon went out to inspect his wife’s handiwork. As soon he left, Lemmon’s partner grabbed his rifle and set out after him. Several minutes later, a single shot rang out. Sometime later, Lemmon’s partner, rifle in hand, returned alone. The partner ordered Cloud Walker to prepare him supper, and to boil the remaining venison and pack it with the bannock. He told her that he planned to leave the next morning, and that Cloud Walker and her son should remain at the cabin and await his return. When Cloud Walker glanced fearfully in the direction of the horse corral, he struck her across the face and told her that her husband wasn’t coming back. The man quickly finished his meal, headed into the cabin and tore the place apart, ostensibly searching for Lemmon’s hidden gold. Cloud Walker, fearing for her son’s life, gave the boy his supper and told him to take a blanket and hide in the woods. Then she herself returned to her teepee, grabbed a blanket and found shelter under a rock ledge close to the creek. That night, as the angry miner called out her name, Cloud Walker made her way to the corral. There, she found the body Lemmon, who had been shot in the back. The Indian sat next to her husband’s corpse until the break of dawn. In the early morning, Cloud Walker returned to the camp and started a cooking fire. The prospector awoke shortly thereafter and joined her, demanding his breakfast. The Blood made the man a meal of deer meat and beans. Cloud Walker knew that the prospector, who was nearly ready to depart, would almost certainly leave her and her son to die alone in the wilderness without supplies or horses. Alternatively, he might kill her and her son, as he did Lemmon. Determined to avenge her husband, and to secure her own future and that of her son, Cloud Walker seized an axe, crept over to the unsuspecting prospector, and split his head open. When she was sure the prospector was dead, Cloud Walker collected her son. She dug up Lemmon’s gold from the secret cache, kept a handful of the dust for herself, and placed the purse on her dead husband’s chest. She covered his body with a pile of brush and proceeded to the mine that he and his partner had laboured on for some time. Resentful and bitter, Cloud Walker put a curse on the diggings, so that any white man who sought it would go insane or perish in the wilderness. Then, using some of the miners’ blast powder that lay nearby, she buried the gold in a mound of rubble. After a cold camp that night, Cloud Walker resolved to return to the Blood Reserve with her son. The two Indians set out into the wilderness the next day. Unfortunately, due a torrential rainfall that lasted for days, the pair soon became lost. They travelled for several days through wild terrain, crossing mountain streams on horseback. After an encounter with a grizzly bear, their pack horse fled into brush, leaving them without any supplies.

Cold, hungry and miserable, Cloud Walker and her son came to a rapids in the Elk River, near present-day Sparwood, British Columbia. After camping at the edge of the river for several days, waiting out a rainstorm, Cloud Walker decided that it was time to cross. After tying her son’s feet underneath the belly of his pony, Cloud Walker mounted her own horse. Together, the two Bloods and their mounts plunged into the freezing white water. After a rough ride on the current, Cloud Walker and her son were able to struggle up onto the eastern shore. Exhausted, they made camp on the spot. The next day, the two Indians made their way through the mountains and over the summit of Crowsnest Pass. They spent the night in a makeshift lean-to composed of pine boughs. It was on the following day that they stumbled upon the homestead belonging to Florence Kroesing’s mother.

Philip H. Godsell’s Story

Background

Another article on the Lost Lemon Mine was published in the March 1950 issue of the magazine Adventure. This piece, entitled Fatal Gold, was written by Canadian folklorist and ex-HBC inspector Philip H. Godsell.

The Story

Godsell’s version of the tale of the Lost Lemon Mine is identical in many respects to the story told by Lafayette French. In this version, the co-discoverers of the golden bonanza in the Canadian Rockies were Blackjack McDonnell, “the original discoverer of the rich Cariboo diggings”, and Bill Lemon. These two “rock rats” travelled from Tobacco Plains to the North Saskatchewan River in the company of well-armed prospectors led by a half-breed named Emil La Nouse. After panning the South Saskatchewan, the prospectors headed west. Blackjack and Lemon eventually split from the main party and follow “an old Indian lodge-pole trail up High River towards the purple-shadowed Rockies, while La Nouse headed for the notorious whisky-fort of Stand-Off.”

The prospecting partners found a stream that yielded promising quantities of gold dust and decided to follow it to its headwaters. Somewhere along they way, they decided to dig two shafts to bedrock, which gave up even more gold. “Suddenly,” Godsell wrote, “Blackjack emitted a roar like an infuriated buffalo bull. The hoofs of one of the cayuses had turned over the sod, exposing a ledge of rock that seemed simply loaded with gold. Traders who saw samples of this rock at Fort Benton later described it as resembling a body of solid gold with a little rock shot into it.”

That night, the partners argued over whether to avail themselves of the gold immediately, or to return to civilization to recruit miners to help them liberate it from its terrestrial prison. Blackjack wanted to go for help, while Lemon was adamant that they stay and “work the diggin’s for all they’re worth.” After a heated row, the two prospectors crawled into their bedrolls. Once Blackjack was asleep, Lemon split his head with an axe.

According to Godsell, the Stoney braves who witnessed the murder were named Calf Child and Medicine Owl. These mischievous warriors, seeing that “Lemon appeared half-crazed with the thought of his terrible deed… added to his distress by whistling, moaning and making other weird and ghostly sounds.” Lemon fled the scene of the crime at dawn, whereupon the two Stoneys filled in the shafts and concealed them with brush.

Lemon rode back to Tobacco Plains and confessed his sin to his old friend, Father Le Roux. He also showed the priest a sample of the gold he had taken from the bonanza he and Blackjack had discovered. Immediately, Le Roux tasked half-breed mountain man John McDougall with burying Blackjack’s corpse. McDougall did as requested, finding Blackjack’s “wolf-gnawed remains” with little difficulty and covering it with a mound of stones. No sooner had he left the site, however, than Stoney braves, on the orders of Bearspaw, their chief, tore down the cairn and scattered the stones, obliterating “the last trace of the whites and their discovery.”

The rest of Godsell’s tale is largely congruent with that told by Lafayette French. Following McDougall’s return to civilization, a crazed Lemon led a party of miners (one of them Swiftwater Bill of Klondike fame) on a fruitless search for his lost mine. Following their misadventure in the Canadian wilderness, Father La Roux tasked John McDougall with leading a similar expedition. Unfortunately, the mountain man drank himself to death at Fort Kipp. A third party set out in search of the Lost Lemon Mine the following year and returned empty-handed after narrowly avoiding a raging forest fire beyond Crowsnest Lake. Lemon, at the behest of Father La Roux, led a final fruitless expedition the year after that.

Years later, Lafayette French went in search for the Lost Lemon Mine, equipped with a map to the diggings drawn by Lemon himself, who had went to live with his brother on his ranch on the Texas Panhandle. French returned from his first trip into the Canadian Rockies stricken with some strange malady. When he recovered, he sought out survivors of the previous expeditions.

Eventually, French learned that Calf Child, one of the two Stoney braves to witness Blackjack’s murder, knew the location of the lost diggings. After much effort, he finally convinced the Indian to lead him to the gold. While waiting for the arrival of French’s prospecting partner George Emerson, Calf Child spent a night at “George Sage’s place- an abandoned ranch on the middle fork of the High River… That night, the Indian died suddenly in convulsions.” To make things even more bizarre, Calf Child’s son-in-law died in the same mysterious manner on the night Calf Child’s body was brought to Morley for burial.

Eventually, the curse that hung over Lemon’s lost gold caught up with Lafayette French. Upon returning from his last excursion into the mountains, French spent a night in George Emerson’s cabin. The cabin mysterious caught fire and burned to the ground. French managed escaped the inferno, but not before suffering terrible burns. Earlier, he had written a letter to friend indicating that he had finally “located IT, and was going to High River in a couple of days to tell him everything and enlist his aid.” When he finally arrived in High River, French was unable to utter a word. He died there in silence, taking his secret with him to the grave.

Sources

- The Mystery of the Lost Lemon Mine, 1993, Ron Stewart

- Frontier Book No. 4: The Greatest Mystery of the Canadian Rockies- The Lost Lemon Mine;1968; Dan Riley, Tom Primrose, Hugh Dempsey

Jeff Freeman

We are trying to get ahold of Ron Stewart. Doing research on the on The lemon Gold mine. We have a podcast and would like to interview him. Thanks for any help you could provide. Our podcast is Jfree906 if you need to check is out.

Tim H.

If you published this in 2014, you should know better than to use the outdated and offensive language contained in this article.

If you are merely quoting older works, then that should be clearly stated; e.g., quotation marks, footnotes, citations.

If you are using older works as source material extensively and/or verbatim, then you are a plagiarist.

I am seriously unimpressed. And it doesn’t matter if this isn’t a scholarly article, there are still standards.

Kal

Damn, Tom. Get his ass.

murray wilson

Awesome Tale