Back to The Riders of the Plains.

The following is an excerpt from The Riders of the Plains: A Reminiscence of the Early and Exciting Days in the North West (1905), by Cecil Edward Denny. This work is in the public domain.

Continued from Chapter XI – Slaughter of the Buffalo.

Chapter XII

Severe Trip to Helena

COL. MACLEOD, ABOUT the beginning of March 1875, found it necessary to proceed south to Helena, a town in Montana some 250 miles south of us, to communicate with the authorities in Ottawa by telegraph on police matters for the coming summer. He determined to proceed south on horse-back with two pack horses, a guide, an officer and two men. I accompanied him, together with Potts the guide, Sergt. Cochrane, and C. Ryan, constable. We took a pair of blankets each, bacon and hard tack being our provisions, and a supply of oats for the horses. We left March, 15th, the weather being cold but fine, and encamped at Whoopup the first night.

On leaving there the next morning Mr. Akens, who was in charge of that fort, pointed out to us two bright mock suns, or, as they are called, sun dogs, and predicted a severe cold storm before long. He also advised us to remain, but we put no faith in these signs and started out. It turned very cold before night. We camped on the open prairie that night, and felt the cold very much, not having much bedding. The horses also suffered, as the feed was scarce and the snow deep. The next night we made Milk river in a blinding snow storm and blizzard, the thermometer, as we afterwards found, going down to 63 degrees below zero. There was not a stick of wood on Milk river, and the snow was too deep for hunting buffalo chips. We were in a bad plight indeed. We set to work with our knives and scooped out a hole in a large snow bank, and all crept into it with the exception of one man, who took care of the horses, which he did by walking up and down in the snow holding the ends of the ropes fastened round the horses necks. There was no feed for them, and had they been let go it would have been the last of them, and of us. The buffalo were also very thick on the river bottom, being driven down by the storm. They would come quite close and right among the horses. We each took the work of herding an hour at a time, and it was all that we could stand, but it was almost as cold in our snow hole, though we were protected from the wind.

We remained for two nights and two days in the snow bank, with little or no sleep, and what I believe saved our lives was the eating of bacon, which we had no fire to cook. The storm continued, and on the second day we determined to proceed south, as we knew if we remained much longer where we were we would soon be frozen to death. We still saw each day the sun dogs, the foreteller of the storm. On the third morning we all started out on foot leading our horses, which were weak for want of food. The packs kept slipping and we got most of our fingers frozen putting them straight. There was no road or trail of any sort, and we had to trust altogether to our guide, who did nobly. His instinct, it could be nothing else, was wonderful. All that day we were surrounded by a blinding snow storm, so that no land marks were visible, but at night he brought us true to the spot to which he had been steering. This was a rocky butte on the open prairie, among which some springs flowed in the summer.

That day was a hard one on all of us. Ryan was the first to give out. I being in the rear, came up to him sitting on the prairie holding his horse, and on asking him what was the matter, he said “Go on Mr. Denny, you and the colonel. I am done up, and we shall never get in, I can go no further.”

I found that he was wearing a pair of buckskin breeches, which had probably got damp while in the snow hole and had frozen stiff, and after repeated efforts to mount his horse had had given it up as a bad job, and given up altogether. However, I hoisted him on his horse and we joined the rest, and the colonel soon put some spirit into him, but we had good cause to be discouraged. Had it not been for our guide we should never have seen civilization again.

I found that he was wearing a pair of buckskin breeches, which had probably got damp while in the snow hole and had frozen stiff, and after repeated efforts to mount his horse had had given it up as a bad job, and given up altogether. However, I hoisted him on his horse and we joined the rest, and the colonel soon put some spirit into him, but we had good cause to be discouraged. Had it not been for our guide we should never have seen civilization again.

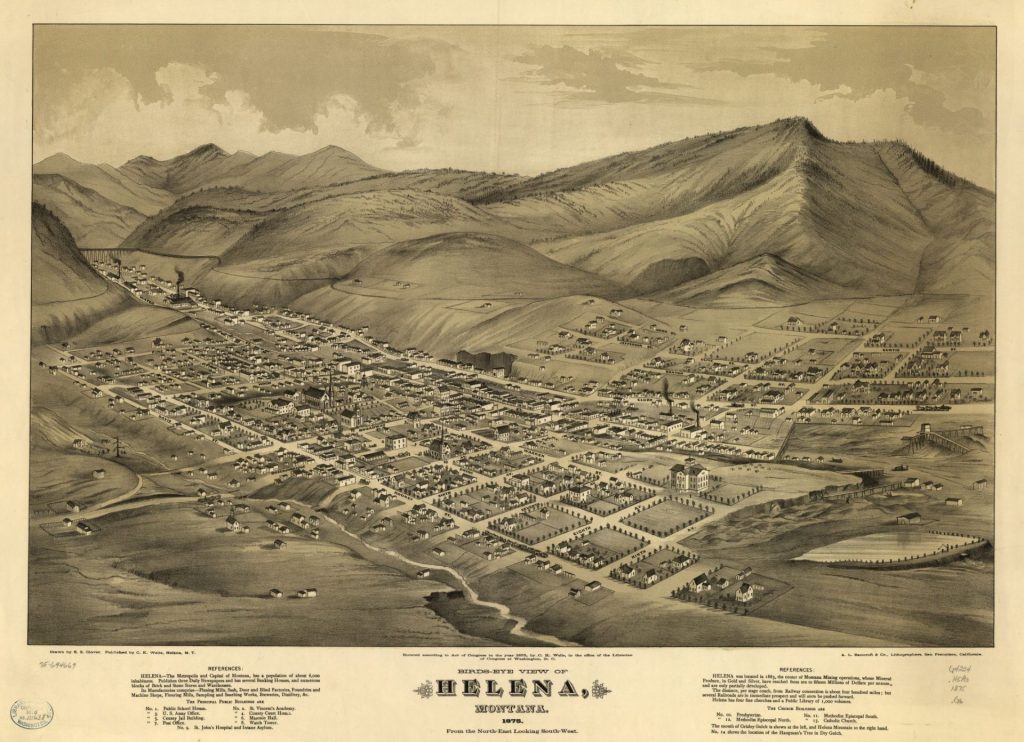

The night at Rocky springs was our last night out, and a miserable one it was. We all lay together, and in the morning were covered with six inches of snow, but the next morning was fine and bright and about noon we made an American trading post, some thirty miles across the line. There was a detachment of American cavalry at this point on the look out for whisky traders, and when they saw our dilapidated outfit coming down the hill, all turned out, thinking the whisky traders were coming to them without their having the trouble to go after them. When they found out who we were their kindness was without bounds. How we did enjoy the warm fires and good food they gave us! We were all more or less frozen. The colonel’s face was frozen, and I lost one of my toes, and was badly snow blind, and had to remain at Fort Shaw. This was an American military post which we reached the next day. I remained there for over a week, joining the colonel in Helena when I recovered. I went down to Helena in a government ambulance and had a most pleasant journey. The road passes through the Prickly Pear Canyon before reaching Helena, and the scenery is of the grandest description. The road runs over the summit of the Rocky Mountains to reach Helena, which lies in a beautiful valley right in the heart of the mountains. Helena, when we visited it in 1875, was a thriving mining town of some three thousand inhabitants, placer mining still going on at the time in the gulches near the town, the water being brought to the workings by flumes of several miles in length. There were some good hotels, at one of which, the St. Louis, we put up, and found the accommodation very good indeed. There were two banks and several wealthy business houses. The eastern portion of the town was composed of drinking and gambling houses, with several dance houses in full swing. China town was a place to be visited, a separate part of the town being set apart for the Chinese, who made good wages working the old placer diggings. Helena had only been in existence a few years, gold being discovered by a party of miners in 1856. They had worked at prospecting all the summer without success, and their provisions were nearly expended. They determined on one more chance in that gulch, when they made a rich find, naming the spot Last Chance Gulch, on which the town of Helena sprung up. It is now a city of 20,000 inhabitants, and the terminus of the St. Paul, Minneapolis and Great Northern railroad. The placer mines are worked out, but rich quartz mines are now in operation. Much farming and stock raising is also done in the district, and Helena is now the capital of Montana.

We remained some weeks in Helena, and were most hospitably treated by the American officers stationed there, and every courtesy was extended us by the leading civilians. We came across some of the men who deserted from Fort Macleod the month before, who had, after great hardships, arrived in Helena, and found their dreams of wealth easily acquired, not up to their expectations. Most of them, much ashamed, came to see Colonel Macleod, and endeavored to be taken back. A few of the best men returned with us to Fort Macleod.

My return trip to Macleod was a pleasant one. The spring having opened, the only trouble we had was in crossing the rivers, which were high, and the ice was just breaking up. There being no boats on the rivers in those days, we crossed as best we could, the crossings sometimes being very dangerous. Everything had gone on well at Fort Macleod in our absence. Several more arrests had been made of whisky traders and some Indians for various offences, but the Indians had been throughout the winter very friendly. Considerable work had been done on the barracks, larger stables having been built; some more buildings had also been put up in the village, and one or two more stores added.

On Colonel Macleod’s return in July from his second trip to Helena, Superintendent Irvine came with him on a visit, and when he left he took the prisoners under sentence overland to Winnipeg. He had come up to Benton by river steamer, and from there 180 miles by stage to Helena, his trip back being a much harder one than coming up.

Inspector Walsh, who had spent the winter at Sun river with most of the police horses in charge, which had been sent down there to winter, returned with Colonel Macleod, bringing the horses back with him, and also a good number of serviceable animals purchased in Montana for police purposes, which we were much in need of. Colonel Macleod had received instructions to build a fort in the Cypress hills, some 200 miles east of Macleod, as that section was also infested by whisky traders, the Cypress district being not far from the line. It was also a great hunting ground, and our Indians were continually at war with those across the line, and horse stealing between them was a regular business. The object in building a fort and stationing men at this point was to put a stop to this lawlessness. One troop of 50 men only could be spared, and in the early spring of 1875 Major Walsh, with B. Troop, proceeded with the baggage transport and horses to this point, where they built that summer a very substantial fort, almost in the centre of the Cypress hills, out of good material. There was plenty of pine timber to build with. This fort was named Fort Walsh, after the officer building and commanding it, and they had their hands full of work that summer in building, and in other police work.

It was also determined that one troop should proceed from Macleod north as far as the Red Deer river, two hundred miles from Macleod, and one hundred south of Edmonton, and there await the arrival of General Selby Smyth and escort of police from A troop, stationed at Edmonton.

General Smyth was an imperial officer in command of the Militia forces of Canada, and was to make the first tour of the North West Territories ever made by the authorities, under police escort. He was to make the journey from Winnipeg to Fort Pelly, at which point Colonel French, in command of the force, had built a fort and wintered with 100 men of D and E troops, and be escorted from there up the Saskatchewan to Edmonton, at which point Inspector Jarvis, with one troop, had arrived the previous autumn and wintered in the Hudson Bay Company’s fort. They would escort him from there, to be met by a troop from the south at the Red Deer river, and then proceed south to Macleod, and across the line to Fort Benton, and back home down the Missouri river, taking rail at Bismark. Colonel Macleod detailed F troop for the journey to meet the general, himself accompanying the troop, Inspector Brisbois being in command, and myself the second officer.

The troop consisted of 50 men, with a good troop of horses in good condition, also wagons enough for all supplies, tents, forage, and all the troop baggage, as it was not intended that this troop should return to Fort Macleod, but after meeting the General at the Red Deer we were to remain at some point on the Bow river, half way between Fort Macleod and the Red Deer, and at a point to be chosen by Colonel Macleod a post was to be built and occupied by this troop.

The Bow river was the headquarters for hunting and winter camping for most of the Blackfeet tribe of Indians, also the Sarcee and Stony tribes, and many whisky traders slipped into that country from the south without our being aware of it at Macleod. There were hundreds of miles of frontier by which they could cross over into the Territories without anyone being the wiser, and their whisky could be disposed of, and they could get out of the country, before men could be sent up to the Bow river.

We, therefore, were prepared to start north early in June with a rather more pleasant march ahead of us than we had the previous year, as we were by that time getting acquainted with the country and the people, both Indians and whites. The country we had to travel through was well watered, with wood on the rivers, feed for horses, and game in abundance.

We did not start on this northern trip until August 18, 1875. Colonel Macleod had returned to Helena in May, and there was met by Lieutenant-Colonel Irvine, who had been sent from Canada by the government on a special mission regarding the extradition of men implicated in Cypress hills massacres. These men were tried in Helena, but got clear. Colonel Macleod and Irvine did not return to Fort Macleod until August, Colonel Irvine being then appointed Assistant Commissioner, vice Macleod, appointed Stipendiary Magistrate.

B Troop had started for Cypress in May, and had their fort built by the time F troop started north in August; they had also done much good work in stopping the whisky trade and horse stealing round Cypress.

They found the district full of Indians from all parts of the country and from across the line, who were continually coming into collision with each other, and they had their hands full, with so few men, to stop this, but the work was well done, and things were going on quietly by the following spring, without having any direct conflict with the Indians.

We left everything going on quietly at Macleod. The whisky trade was pretty well broken, and quite a village was springing up at that place. The Indians had plenty of buffalo meat, and would be out on the plains for the summer. Captain Winder remained in charge at Macleod, with one troop of 50 men, and with plenty of work ahead of him in finishing the fort and outpost work. Another large Benton firm, Power and Bros., had opened a store at Macleod, and supplies were plentiful, although at an enormous figure. It is not to be wondered at that these firms became very wealthy a few years after, considering the amount of contract supplies purchased from them at very high figures, and it always seemed the greatest pity that this amount of money should all go out of Canada, as it did for some ten years, amounting to some millions of dollars, and that no Canadian or English firm had a finger in the pie.

Continued in Chapter 13 – Journey to Red Deer.

Leave a Reply